Energy Balance

For their projects, students will choose a type of food that begins as batter and needs to be baked, such as a brownie or cupcake. In the first part of their projects, students will explore how much physical activity they would need to complete in order to expend the same amount of energy as is contained within the food. This will give students a greater appreciation for how food can contribute to weight gain and obesity. Students will calculate the number of kilocalories contained within their food and then choose a specific type of exercise in which the amount of work or energy expended can be easily calculated. We will use climbing stairs as an example later. Finally, students will calculate how much of their exercise needs to be completed (how many stairs need to be climbed, for example) to “burn” or expend the energy contained within their single brownie or cupcake.

In order to understand energy balance in the context of food and calories, students must first understand the law of conservation of energy in physics and the first law of thermodynamics. Students will need to know the definitions of work, kinetic energy, potential energy (especially gravitational potential energy), and heat loss (in the form of friction), and the equations for calculating them. In addition to these concepts in physics, students may need to convert the unit of weight of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats from pounds or ounces to grams if they are using a homemade recipe and also the energy stored from kilocalories to kilojoules.

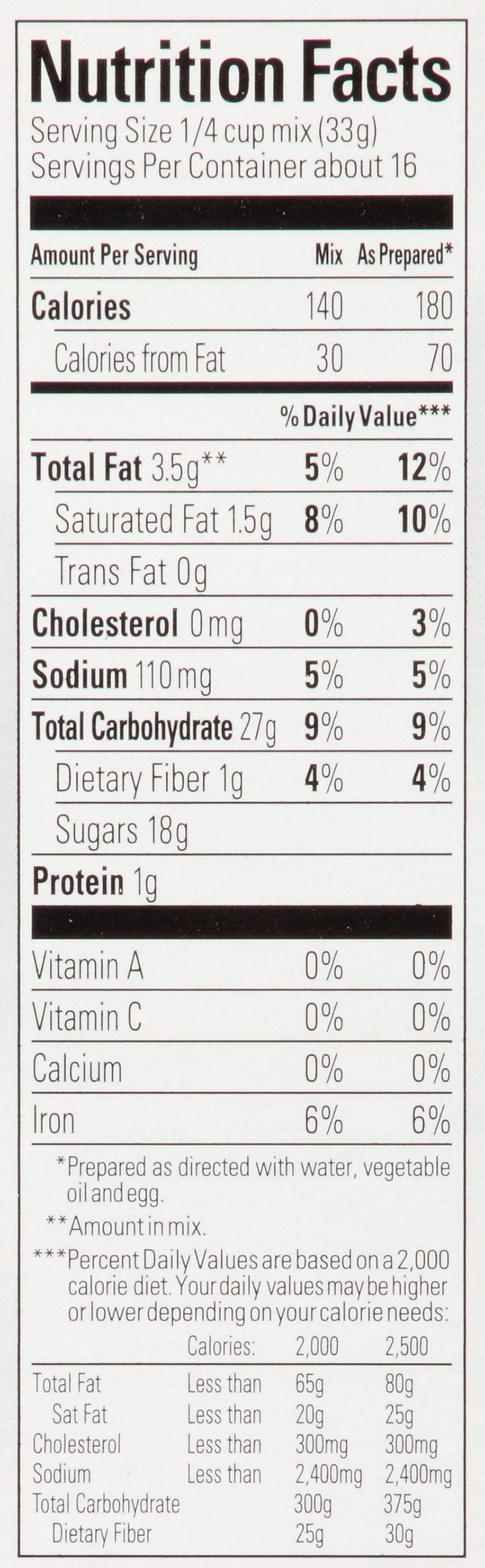

Figure 1: Nutrition label for a brownie product

To begin, students will need to calculate the amount of energy in their food of choice. The knowledge they need will depend on whether they buy a mix or bring a homemade recipe. In the case that a boxed recipe is used they will need to use a nutrition label like the one shown above to determine the number of kilocalories in their single brownie, for example. As shown in Figure 1 above, brownie mixes will almost always show you two Calorie values, one for the dry mix, and one “As Prepared” after adding some wet ingredients such as milk, eggs, and oil. This can make our calculation tricky unless we know exactly one sixteenth of the batter was used for our sample. A solution would be to measure the mass of any added wet ingredients when making the batter, add that to the total mass of the dry mix, and then use the mass of the individual sample relative to the total mass of the recipe to find the Calories in the individual sample. For instance, if 45 grams of water, 109 grams of oil, and 100 grams of eggs were added to the dry mix, then our total mass of the batter would be 782 grams. If the batter of our individual brownie sample has a mass of 50 grams then that would represent about 6.4% of the total batter and thus 6.4% of the total 2,880 Calories, assuming the ingredients are distributed evenly. This would mean we have roughly 184 Calories in our individual sample. Since the energy exerted from exercise will be calculated in Joules, the students need to convert this amount of energy in Calories to Joules. One kilocalorie is equal to about 4,184 Joules or 4.184 kilojoules so this means our individual sample contains about 770,000 Joules of energy. A summary of the calculation is shown below.

Mass of water: 45 g

Mass of oil: 109 g

Mass of 2 eggs: 100 g

Mass of dry mix: 33 g/serving * 16 servings = 528 g

Total mass of batter: 45 g + 109 g + 100 g + 528 g = 782 g

Mass of individual sample: 50 g

Percent mass of total: 50 g / 782 g * 100% = 6.4% of total mass

Percent Calories of total: 6.4% of total Calories

Total Calories in prepared mix: 16 servings * 180 kcal/serving = 2,880 kcal

Calories in sample: 2,880 kcal * 6.4% / 100% ≈ 184 kcal

1 kcal ≈ 4,184 Joules

Joules in sample: 184 kcal * 4,184 Joules/kcal = 769,856 Joules

Alternatively, students may have prepared their sample from scratch using a homemade recipe. If this is the case, additional information will likely be needed. To illustrate how to calculate Calories using a homemade recipe, we will use a simple brownie recipe from Allrecipes.com11. First, it may be useful for students to know how many Calories are contained within one gram of each type of macronutrient. Carbohydrates and proteins both contain about 4 kcal per gram, fats contain about 9 kcal per gram and alcohol contains about 7 kcal per gram12. This can give students better sense for the energy contained within specific ingredients. However, more information is needed since many ingredients like flour or eggs, for instance, contain more than one macronutrient. Therefore, additional resources are needed. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) FoodData Central is a great tool to get a reliable approximation of Calories contained within specific ingredients13. Using this tool, we can generate the following table based on the Allrecipes.com recipe mentioned above.

Table 1: Allrecipes Brownie Recipe Data Collected with USDA FoodData Central

|

Ingredient

|

Amount

|

Amount in grams

|

Calories

|

Energy in Joules

|

|

Butter

|

1/2 cup

|

113.5

|

815

|

3,409,960

|

|

White Sugar

|

1/2 cup

|

188

|

724

|

3,029,216

|

|

Eggs

|

2 large

|

100.6

|

148.8

|

622,579

|

|

Vanilla Extract

|

1 tsp

|

4.2

|

12.1

|

50,626

|

|

Cocoa Powder (Unsweetened)

|

1/3 cup

|

28.7

|

65.3

|

273,215

|

|

All-purpose flour

|

1/2 cup

|

62.5

|

227.5

|

951,860

|

|

Salt

|

1/4 tsp

|

1.5

|

0

|

0

|

|

Baking Soda

|

1/4 tsp

|

1.15

|

0

|

0

|

|

TOTAL MASS

|

|

500.15

|

|

|

|

TOTAL KCAL

|

|

|

1992.7

|

|

|

TOTAL JOULES

|

|

|

|

8,337,457

|

Next, students will need to understand the physics behind physical exercise. Most students will likely be familiar with the idea that energy cannot be created nor destroyed, only transformed or transferred. In physics, we call this the law of energy conservation or the first law of thermodynamics, which states that the total energy within an isolated system will remain constant. If we consider the example of climbing stairs, we can say that the initial energy (Ei) plus any external work (Wext) put into the system will equal the final energy (Ef). This can be represented by the equation below.

Ei + Wext = Ef

This simple equation can be expanded to show the specific components contributing to energy totals on both sides of the equation. To do this we can say that the initial potential energy at the bottom of the stairs (PEi), plus the initial kinetic energy (KEi), plus any external work put into the system will equal the final potential energy at the top of the stairs (PEf), plus the final kinetic energy (KEf), plus any heat loss due to friction (ΔET for change in thermal energy). This can be summed up with the following equation.

PEi + KEi + WEXT = PEf + KEf + ΔET

Before students can fully apply such an equation to a physical activity like climbing stairs, they need to understand how each of these components is defined and calculated. First, potential energy can be broadly defined as stored energy resulting from the position of some parts of a system relative to other parts. In this case, however, we only care about gravitational potential energy or the energy the person has due to their height after climbing the stairs. The formula for this type of potential energy is PE = mgh, where m is mass, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and h is height. Both m and g should remain constant in the case of a person climbing a set of stairs. The variable that will change from one side of the equation to the other is the height. To make our equation simpler we can set our initial or starting height to 0 meters, cancelling out the entire “mgh” term on the left side of the equation. Kinetic energy (KE) can be simply defined as the energy something has due to its motion and can be calculated with the equation KE = ½mv2, where v is the object’s velocity. Kinetic energy is not very relevant in this case since we can say the person is not moving before climbing the stairs and that they have stopped moving after reaching the top of the stairs. Therefore, v in each “½mv2” term will equal zero, cancelling them out on both sides. Work in physics is defined as the product of the force applied to an object and a parallel displacement, and is measured in Joules (J). For example, the work done by a rightward force of 10 Newtons (N) that displaces an object 5 meters (m) would be 50 Joules (J). The equation for work is therefore W = F*d, where d is displacement and F is the force exerted parallel to the displacement. If the force is not already parallel to the displacement then the equation can be modified to W = FcosΘ*d, where theta (Θ) is the angle between the force and the displacement of the object. In this case of climbing stairs, we will assume that the force exerted by the person in moving horizontally on the staircase will be small compared to the force of climbing vertically. Thus, we will neglect all horizontal force and only use the force exerted to move one’s body in the upward/vertical direction. The equation for force is mass multiplied by acceleration, or F = ma. In this case of climbing stairs we will assume that the person is moving vertically upward at a constant velocity, therefore the acceleration or “a” used to find the force exerted will be equal to the positive value of acceleration due to gravity g, or 9.8 m/s2 (making the net acceleration zero, hence a constant velocity). This, of course, would require students to reveal their mass, which may be a little too personal for some students. Because of this, it is suggested that 70 kg be mentioned as an alternative to using your own mass since this is a common mass of a human being often used in calculations. The heat loss component of this equation refers to the energy lost due to heat because of friction (usually between the object and the ground). Here we will assume the person is climbing the stairs in a very efficient manner and that energy lost due to friction is negligible. Thus, we can set this term to zero and we can begin to calculate.

With students now familiar with each of the components of the energy conservation equation, we can then use the amount of energy in the unit of Joules contained in the chosen food to calculate the height gain needed when climbing stairs to offset or “burn” an equal amount of energy. Looking at our law of conservation equation and assuming that the starting height is zero, we can cross out the terms PEi, KEi, KEf, and ΔET as shown below.

PEi + KEi + WEXT = PEf + KEf + ΔET

WEXT = PEf

We then find that the work put in by the person climbing the stairs will equal the gravitational potential energy gained due to the height change. This is the amount of energy exerted by the person's exercise of climbing the stairs. If we want to calculate the height gain required to “burn” the energy contained in our individual brownie sample, we can simply set the brownie’s energy in Joules equal to the final potential energy. If we then consider that the American architects typically use a height for each stair step of about 0.19 meters (or about 7.5 inches), we can then calculate the required number of stairs climbed to expend the energy contained in the brownie. Assuming, there are typically 12 steps in a flight of stairs, we can also calculate the number of flights required. An example of the calculation is shown below using a person with a mass of 70 kg.

Brownie Energy in Joules = PEf

769,856 J = PEf

769,856 J = mghf

769,856 J = (70 kg)(9.8 m/s2)(h)

769,856 = 686h

h ≈ 1,122 m

Average stair step ≈ 0.19 m tall

1,122 m / 0.19 m per stair ≈ 5,905 stairs

5,905 stairs / 12 stairs per flight ≈ 492 flights of stairs

For a 70-kg person to burn off the 769,856 J (or 184 kcal) contained in our one brownie, he or she needs to climb about 5,905 stairs or 492 flights of stairs. It is important to note that this is an approximation with an assumption that a constant force is applied and neglects horizontal displacement. Because our movement is not 100% efficient it is likely to require significantly fewer stairs to expend 184 kcals. For example, according to Acefitness.org’s “Physical Activity Calorie Counter” it would take only about 20 minutes of climbing stairs for a 70-kg person to burn 184 kcals14. At a rate of 90 stairs per minute, a medium pace for climbing stairs, it would only require 1,800 stairs to burn 184 kcals. Still, this lesson activity can be a good way for students to gain appreciation for the amount of energy contained in the food we eat.

Thermodynamics

The second part of the project involves cooking the batter of the students’ food and experimentally determining the thermal diffusion constant of the batter. This part is inspired by Rowat’s 2014 paper, “The Kitchen as a Physics Classroom” published in Physics Education. This paper contains many great ideas for hands-on physics labs relating to food10. Here, the experiments are modified to be more suitable for a high school physics classroom. Rowat et al. describe thermal energy transfer within food with the equation below where T(t) is the temperature of a food after a certain amount of time, Tin is the initial temperature of the food, Tout is the external temperature or temperature of the oven cooking the food, t is time, τ0 is the time constant, L is the distance travelled by the thermal energy, and D is the thermal diffusion constant.

T(t) = (Tin - Tout)e –t/τ0 + Tout; τ0 = L2/4D

We can use this equation to help determine the proper cooking time for a food sample given its size if we know the thermal energy diffusion constant. Although we may have some potential uses for this equation, we can focus primarily on a simpler equation L = √(4Dt), which shows that the distance traveled by the thermal energy is proportional to the square root of time. By making a few assumptions, we can use this equation along with a relatively simple experiment to roughly determine the diffusion constant (D) for our batter. With a food, such as a brownie or a cupcake, which starts as batter and solidifies, the batter will have a certain temperature at which it solidifies. If we wait until the outer layer solidifies, the solid layer should progress at a rate that is proportional to the square root of time, thus the equation L = √(4Dt), where “L” is the distance progressed by the solid layer. Once the outer layer of the brownie solidifies, we can time how long it takes for the solid layer to reach the center, and then use this time to calculate the thermal diffusion constant for our sample batter. We can do this by rearranging our L = √(4Dt) equation to solve for the thermal diffusion constant to get D = L2/4t. We can calculate this thermal diffusion constant where our initial batter temperature is approximately 21°C (room temperature) and our external or oven temperature is 175°C. We can then use the calculated diffusion constant to estimate the cooking time needed for a batch of brownies of a different size (L or length from outer edge to center, radius in the case of a circular cooking dish) if we use the same or similar temperatures. It is worth noting that this equation would ideally be applied to foods with more of a spherical shape, like a Thanksgiving turkey for instance, where “L” is roughly constant from any outer surface of the food. In the case of brownies, for example, if a large baking sheet is used (increasing the length and width) but the height of the brownies remain only one or two inches then the center may solidify from the top and bottom before the heat actually diffuses through batter from the sides. Such considerations offer incredible opportunities to question students about the limitations of our equations.

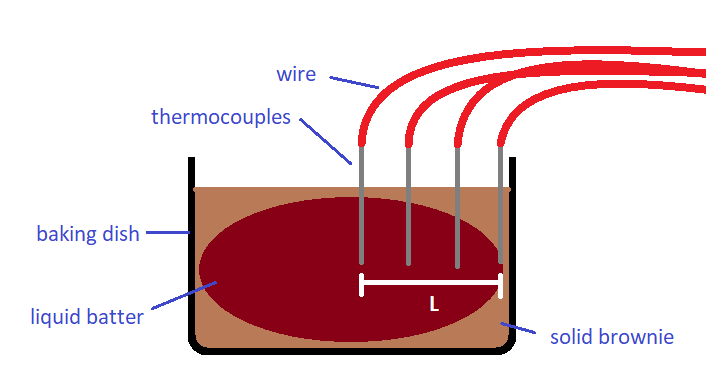

There are several methods we can use to time the progression of the solid layer of the brownie towards the center. Both are similar in concept, but one is higher tech and will likely yield a more accurate thermal diffusion constant. Unfortunately, this higher tech option is likely to be more expensive and/or more difficult to implement in the high school physics classroom. This higher tech option involves using thermocouples to read temperature inside the brownie as it is cooking. If we know the temperature at which the batter solidifies, we will know the approximate moment the center of the brownie solidifies based on the temperature reading. Thermocouples are electrical components that generate a voltage when exposed to a temperature gradient. To most effectively read data from thermocouples and have it automatically converted to temperature we would need a data acquisition switch unit, such as the Keysight 34970A/34972A Data Acquisition/Switch Unit. This unit is expensive, however, which makes this method less than ideal for a high school classroom, especially one with a limited budget. Theoretically, it should be possible to measure the voltage generated by the thermocouples with a simple multimeter and then manually convert to a temperature using a thermocouple temperature voltage table. This would likely prove very difficult to do in an efficient fashion while cooking the sample within a toaster oven, for example. For these reasons, a much simpler, although less accurate, method will be discussed. If the more advanced thermocouple option is chosen, however, a possible setup is shown below in Figure 2. This figure is likely to bring clarity to the setup for both methods.

Figure 2: Possible Setup of Brownie Sample with Thermocouples

A significantly simpler method can give us a very rough estimate of the diffusion constant. This can be done by frequently probing the brownie with toothpicks in locations similar to those of the thermocouples in Figure 2. It is suggested this experiment is repeated at least 3 to 4 times so as to more accurately pinpoint the time at which various distances from the edge of the brownie are solidifying. By repeating the experiment several times and fine-tuning the time it takes for the solid layer of the brownie to reach the center, the oven can be opened fewer times, which is an obvious concern since we will not want to continue disturbing the temperature of the oven, Tout. While this experiment has its obvious limitations, if care is taken it can give us a rough estimate of the diffusion constant and will help students gain a better understanding of thermodynamics. Interestingly, Rowat mentions that one of her students was so confident in their experimentally determined equations that they used it to “estimate the cooking time of her family’s Thanksgiving turkey.”10

It is important to note that whatever recipe or mix is chosen it should be of a consistent nature so that thermal diffusion constant can be expected to remain constant throughout the batter. Therefore, using brownies with chocolate chips or M&Ms, for instance, is not advised. Also, it is important to preheat the oven and try to open the oven door as few times as possible in order to keep the oven temperature (Tout) as stable as possible. Other notable limitations of this experiment include energy loss due to water evaporation from the surface of the batter, changes to the heat diffusion constant after solidification of the batter, minor amounts of convection while the batter is still fluid, and other factors. That said, probing students about these limitations and the accuracy of their estimates is likely to provide important training in science and engineering.

Lastly, as an example, we can cook a circular brownie with a diameter of 5 centimeters (cm) where it is 2.5 cm from any point along the outer edge to the center of the brownie (2.5 cm is our L). If we experimentally determine, using either previously mentioned method, that it takes 10 minutes, or 600 seconds, for the brownie’s solid layer to reach the center, what is the estimated diffusion constant? This problem can be solved by the calculation shown below.

D = L2/4t

D = ?

L = 2.5 cm

t = 600 s

D = (2.5)2 / (4*600)

D = 6.25 / 2,400

D = 0.0026 cm2/s

The thermal diffusion constant of the brownie batter is 0.0026 cm2/s.