At the beginning of this seminar, originally called "Writing about Words and Images," the Fellows and I set ourselves the goal of answering a deceptively simple question: Do the ways in which we analyze a subject depend upon whether it is a verbal text or a visual image? We broached this question so that we could think about three age-old problems: How are images and words are related to each other? Are they by nature different from each other? Can they be understood by analogy to each other? The hunch about the complicated issues to which these problems would lead turned out to be accurate, but our eventual answer to our first question might seem to be a truism. During our final meeting we concluded that, yes, there is a difference between how people write about words and images; but that difference has little to do with the nature of those two media; rather, we realized that a person who has studied words for years is more likely to focus first on the formal features of a verbal text than someone equally versed in the analysis of images, just as a person used to studying images is more likely than a literary critic to ask initially how the techniques of a picture create its meanings. On the principle that the journey is more important than the destination, I don't think that there is any reason to bemoan the fact that we did not come to a theoretical breakthrough on problems that have bedeviled thinkers since Plato and Aristotle. In fact, for us as teachers, it was useful to be reminded how much what our students are able to learn depends on what they already know. Moreover, a seminar devoted to developing projects that link verbal and visual texts is particularly suited to the image- and media-saturated world in which our students, for better or worse, will have to find their places.

In our theoretical considerations of the three basic word-image problems, we considered a wide range of ideas – among them, the classical dictum that a picture is a mute poem and a poem, a speaking picture; Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's concept of words and images as neighbors who should be separated by a sturdy fence; and W. J. T. Mitchell's conviction that all representations are mixed-media

imagetexts

. Also useful was the thinking of Scott McCloud as it is presented in the chapter of

Understanding Comics

in which he sets out seven different ratios in which words and images can be combined. Equally important, I think, is the example that McCloud offers of a writer who composes in both images and words: he communicates his seven ratios by showing how each would look in the panel of a comic strip. In that sense his chapter had its counterpart in the book that served as the backbone of the seminar: Edward R. Tufte's

Visual Explanations

. Tufte's work in information design has been justly celebrated, most recently by a presidential appointment to a committee charged with ensuring the transparency of the federal government's accounts of its use of stimulus funds. Tufte directly confronts the question of whether texts and images are in any theoretically or practically productive way analogous to each other; and his beautifully designed chapters prove again and again that that is the case. To evaluate the applicability of all these different ideas, we read short stories paired with visual images of comparable subject matter, and we also took as test cases two iconic images, Grant Wood's painting

American Gothic

and Dorothea Lange's photograph

Migrant Mother

, as well as one iconic text, "Letter from Birmingham Jail" by Martin Luther King, Jr.

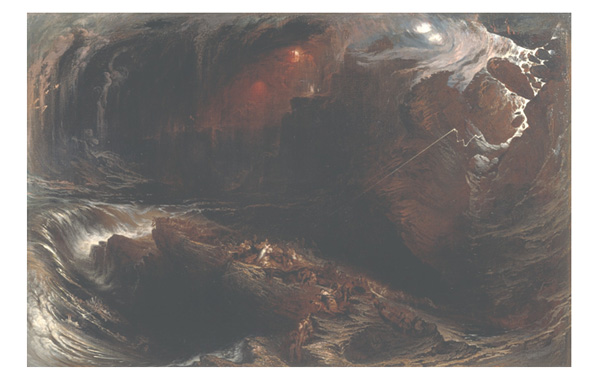

The high point of the seminar came, in my view at least, one Saturday morning when we visited the Yale Center for British Art. Following the method developed by Linda Friedlaender, Curator of Education there, and used by her with students as young as those in kindergarten and as old as those in medical school,<

1<

the seminar participants were asked to look closely at an epic painting depicting Noah's flood,

The Deluge

(1834) by John Martin.

John Martin,

The Deluge

(1834), oil on canvas, 66¼ x 101¾ inches. Reproduced courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

For the first twenty minutes of this session, the Fellows responded to only one question: What do you see? When they were invited to turn their observations of what is physically visible in the painting into arguments about its meaning, they came up with an astonishingly original way to read the painting. The critical literature on

The Deluge

is, from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first, consistent in its conclusions about the status of the human figures in the painting: they are "reduced to triviality, dwarfed by the immense natural [and] divine forces ominously arrayed against them"; or, in the words of another writer, these characters play "the humiliatingly insignificant role of top dressing on a rock of ages."<

2<

From their twenty-minute session of simply listing what they had seen, the Fellows focused instead on the images of damned humanity in

The Deluge

as figures not only to be taken seriously as central to the meaning of the painting but also to be accorded sympathy and even admiration.

John Martin,

The Deluge

(detail)

Despite their obvious peril or perhaps because of it – many of the human beings portrayed in

The Deluge

engage in acts of caring and even piety: a man tries to save a woman from falling into the abyss, many figures raise their arms in supplication in hopes of being saved (hardly an action characteristic of those who have turned away from God), and the pose of the ancient and righteous Methuselah prefigures the crucifixion. According to the account offered by the Fellows in the seminar,

The Deluge

visualizes values of compassion and community. This reading hardly supports a strictly biblical understanding of Noah's flood as God's well-justified destruction of human beings who have become irreparably evil. Identifying the human beings in the painting as objects of sympathy and identification is, no doubt, a distinctively secular reading, one that would have surprised its original viewers, but the analysis that the Fellows offered is, for this reason, a remarkably valuable revision of conventional ways of understanding

The Deluge

. Just goes to show what you can do when you take time simply to look.

The curriculum units presented here similarly prove what can happen when one asks one's students to look. The Fellows who participated in this seminar represented a wide range of subjects and grade levels, from art in K-4 to English and history in middle school and creative writing in high school. Their units reflect this diversity by construing the relation between words and images in different ways and for different pedagogical purposes. Certain commonalities, however, emerge. In the first two units published here, which apply their approaches to both reading and writing, Timothy Grady and Julia Biagiarelli define

image

, not as an object of direct visual perception, but in its traditional literary-critical sense as a verbal evocation of a visible phenomenon. Tim Grady uses the thinking of John Gardner about the nature of fiction to develop a series of writing-workshop activities that help creative writers in high school take full advantage of the descriptive power of language. Like Tim, Julia Biagiarelli asks her elementary-school students to pay attention to the use of images in what they read so that they can produce more fully visualized prose in the stories that they write.

In the next set of units, Laura Carroll-Koch, Carol Boynton, and Heather Wenarsky explore the ways in which images can support writing instruction. Drawing on the findings of neurophysiologists about the two hemispheres of the brain and their separate processing of visual and verbal data, Laura Carroll-Koch created the Trait Mate, a simple but easily elaborated symbol for a fictional character. Developed in her teaching of writing to second-graders, this visual device allows students to plan how to characterize the people in their stories, how to involve them in actions and in relations with other characters, and how to revise their stories into fully visualized narratives. Like Laura, Carol Boynton looks at published research, in her case the studies that prove that the act of drawing improves the quality of student writing. Her unit proposes activities that turn students' eagerness to talk about images into increased abilities to make connections among their reading and their experiences and the world in which they live. Heather Wenarsky's unit, the result of her work with special-education students in the ninth grade, encourages students to become better writers by learning about specific images from a World War II poster to an ad for a laptop and reading about their historical contexts.

In the final and largest set of units, Kristin Wetmore, Medea Lamberti-Sanchez, Sean Griffin, Tara Stevens, and Melody Gallagher all present units that balance words and images for the study of art objects or history or literature. In her unit Kristin Wetmore offers a particularly flexible and extensive way to include two iconic paintings and one iconic photograph in the course of a year-long study of AP art history by placing them in the verbal context of the historical events that they depict. Medea Lamberti-Sanchez also brings together words and images by engaging what she calls "visual vocabulary" to help students in fifth to eighth grades understand the complexities of the American Revolution: portraits, paintings, and maps provide visual incitements to learning and retention. American history is also the focus of Sean Griffin's unit: to prepare students for the reading of Steinbeck's

Of Mice and Men

, he proposes devoting a full week to various activities during which students collect and display images of the Great Depression and analyze their meanings in what Sean calls "mini-research projects." Tara Stevens's project similarly brings together language arts and history to help eighth-grade students as they read one of Chris Crowe's accounts of the tragedy of Emmett Till,

Getting Away with Murder

. Tara's unit offers models of different approaches to the reading of different kinds of texts and images so that students will recognize both the constructed nature of historical accounts and the continuing need to pursue the ideals of social justice. Melody Gallagher, like Tara, is interested in helping students in her fourth-grade art classes think of themselves as agents of change by becoming artists who are also art critics. Melody takes an unconventional route to her pedagogical goals by presenting to young students the works of living artists who take history as their subject. Students then curate an exhibition of their own art – complete with the labels that prove that they understand the meanings captured in their pictures.

Melody Gallagher's unit, like many of the others published here, conjoins different disciplines as it finds new ways to correlate verbal and visual texts, both those that students create and those that they read. Since the career of the great Victorian art critic John Ruskin, it has been commonplace to talk about reading a painting; but in the context of the teaching of writing, it is also appropriate to talk about seeing a text. The revised title to this volume of curriculum units attests to that fact. If most of us take for granted that we write with words, these units allow us to understand anew that we can also write with images – with them as prompts, with them as subjects, and even, as Laura Carroll-Koch's unit demonstrates, with them as records of what students see when they write.

Janice Carlisle

1 Jacqueline Doley, Linda Krohner Friedlaender, and Irwin M. Braverman, "Use of Fine Art to Enhance Visual Diagnosis Skills,"

Journal of the American Medical Association

286 (September 5, 2001): 1020-3.

2 For these quotations see Angus Trumble, "John Martin,

The Deluge

, 1834," in

British Vision: Observation and Imagination in British Ar

t, ed. Robert Hoozee (Ghent: Mercatorfonds Museum Voor Schone Kunsten, 2007), 319; William Feaver,

The Art of John Martin

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), 92.