-How did the courts define who was White?

-What reasons did they offer, and what do those rationales tell us about the nature of Whiteness?

-What do the cases reveal about the legal construction of race, about the ways in which the operation of law creates and maintains the social knowledge of racial difference?

-Do these cases also afford insights into a White racial identity as it exists today?

-What, finally, is White?

Takao Ozawa was a Japanese-American who had lived in America for more than twenty years at the time of his court. However, he like many others had not been born in America. As stated previously in this unit, up until this time period, a pre-requisite for immigration citizenship according to the naturalization laws of 1920, required the applicant to be white. However, with an influx of different ethnicities and cultural groups in and out of Europe, the lines defining race had been blurred. Ozawa utilized his background as a way to advocate for his citizenship. He had married an American woman, attended American universities and spoke English regularly in his home. Ozawa was making an appeal that he culturally fit the modern ideas of what we would consider being white, in addition to the fact that he was visibly white.

He writes to the courts:

My honesty and industriousness are well known among my Japanese and American friends. In name, Benedict Arnold was an American, but at heart, he was a traitor. In name, I am not an American, but at heart, I am a true American. In the typical Japanese city of Kyoto, those not exposed to the heat of summer are particularly white-skinned. They are whiter than the average Italian, Spaniard or Portuguese."

However, the Supreme court disagreed and argued that skin color could not serve as a fundamental reason for one being considered white.

They argue in their decision:

Manifestly the test afforded by the mere color of the skin of each individual is impracticable, as that differs greatly among persons of the same race, even among Anglo-Saxons, ranging by imperceptible gradations from the fair blond to the swarthy brunette, the latter being darker than many of the lighter-hued persons of the brown or yellow races. Hence to adopt the color test alone would result in a confused overlapping of races and a gradual merging of one into the other, without any practical line of separation.”

Here the Supreme Court is laying out in explicit terms to the ambiguity surrounding racial identification. They then decided that the way in which they would determine whiteness would be to trace back to the works of Blumenbach and other anthropologists and scientists who estimated that the origins of whiteness lie within the particular area, including India.

This would prove to be an issue when another applicant, Thind, applied for citizenship using the rationale from the Ozawa case. Bghat Thind, similar to Ozawa, had not been born in the United States. He had immigrated to America and applied for citizenship under the premise that he, being a Sikh man, had been full-blooded Aryan. Utilizing racist, nativist science and reasoning, Thind chooses to challenge the system but utilizing its very own logic. However, his case was still ultimately denied, once again shifting the definition of whiteness in the courts.

They argued:

What we now hold is that the words ‘free white persons’ are words of common speech, to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, synonymous with the word ‘Caucasian’ only as the word is popularly understood.

In essence, Thind did not represent what society viewed as whiteness. He was not white, culturally or on face value. But then what was white? How do we understand whiteness? The pre-requisites cases are an important place of study because it unearths to complexities and ambiguities surrounding race, while also highlighting the real-life consequences that these categories hold in our society.

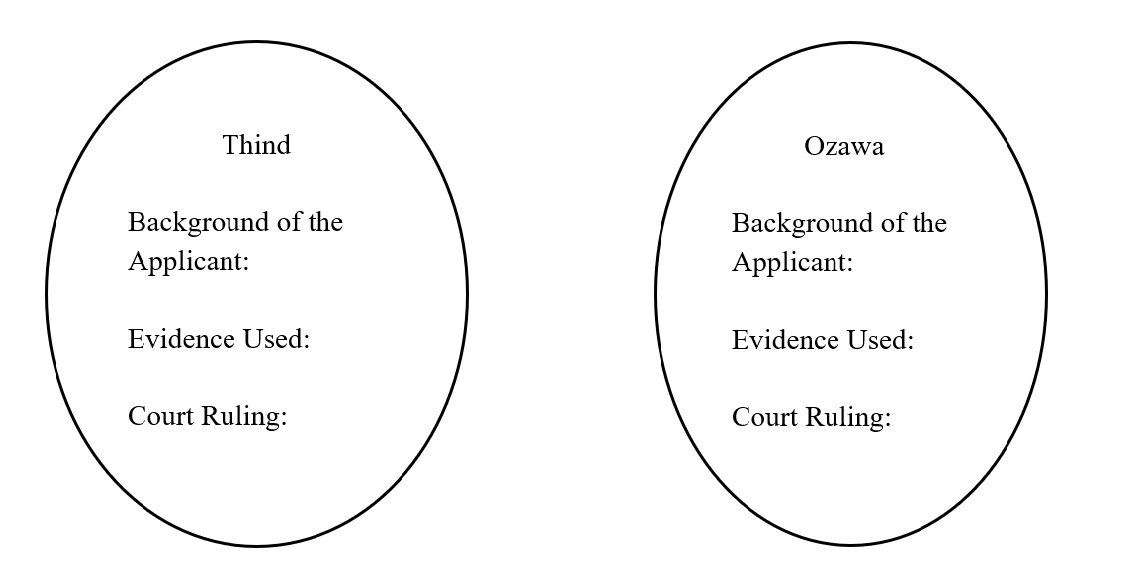

To dig into these court studies, students should be separated into two separate groups and use the jigsaw method to analyze and report back to their peers. One group can be assigned to study the Ozawa case, and the other focusing on Thind, with both groups honing in on the commonalities in the case. The questions that can be used to guide student discussion.

The questions that can be used to guide student discussion can be 1) What evidence do the applicants use to gain citizenship? 2) Why were they denied? What was the ultimate court ruling? 3) How does this court case define whiteness?

An exit ticket for this activity will be for students to return to the original questions that Lopez originally posed and answer one of the questions in an analytical paragraph. This way students are able to summarize what they learned and connecting to the content that they reviewed in class.

An extension/supplemental activity for students might be to watch the PBS special5 on race which discusses the context surrounding the Thind and Ozawa cases and complete another contextualization chart or write a reflection.6