Lesson One: Introduction to Maps

These activities should take place at the beginning of the unit (no prior reading required).

Activity 1

The teacher will first ask students, “What is a map?” Students will spend a minute or two writing a response to this question and sharing their ideas. The teacher will then distribute a selection of maps to small groups of students. Each group will receive one of the following maps:

- London subway map (available online)

- “Queens and Monarchs” (from Solnit’s Infinite City)

- “Poison / Palette” (from Infinite City)

- “The Walk to South School 1964 - 1971” (from Harmon’s You Are Here)

Students will first look over the maps silently for 2-3 minutes and write down what they notice. They will then share ideas and questions in a brief small-group discussion. The teacher will then introduce the following guiding questions for “reading” a map:

- What is being shown or represented in the map?

- Do you notice anything that is left out of the map?

- Does the map show a real, physical place, or something else?

- What text is used in the map? What does it tell the user?

- How is the map decorated? What do the decorative elements seem to say?

- What story does the map tell? What is the user supposed to learn?

In their groups, students will address these questions, discuss, and share their ideas to the entire class.

Activity 2

The teacher will distribute copies of Jorge Luis Borges’ “On Exactitude in Science.” Students will take a few minutes to read the short story and discuss it in their groups. The teacher will then provide discussion questions:

- Is a map like the one described in Borges’ story a useful one?

- Why or why not?

- What would make it more useful?

The teacher will then introduce the Rebecca Solnit quote, “A map is in its essence an arbitrary selection of information.” Students will take a minute or two to respond to this claim and share out. Guiding questions may be provided: is this a reasonable statement? Does the information on a map need to be arbitrary? Why or why not?

Activity 3

Students will draw a map of a place or route that is important to them personally. This may be a small-scale map, such as a desktop or a room in a house, or a larger-scale one, like a city or a country. Students may look to the hand-drawn maps used in the first activity as a point of reference. After they have completed their maps, students should write a brief reflection, addressing the same guiding questions from the first activity. This first map and reflection will be the first contribution to students’ portfolios (or “atlases”), to which they will continue adding the maps they create throughout the unit.

Lesson Two: Mapping Literary Concepts

This set of activities should take place early in the unit, after students have mapped important locations and elements of a familiar text, but before they begin reading Sing, Unburied, Sing.

Activity 1

The teacher will ask students to refer back to the maps they created of a familiar text, and to consider how and why the location(s) of the story was so important. How does it connect to other text elements, such as theme? For example, if a student created a map that shows important locations in The Color Purple, they might write about how the physical distance between Celie and Nettie forces both sisters to persevere in hopes of being reunited one day. After students have spent a few minutes reflecting and writing down their ideas, the teacher will ask for volunteers to share.

Throughout the discussion, the teacher should reinforce that visualizing and illustrating the location of the characters and events in a text can help reveal underlying ideas and meaning.

Activity 2

Students will read the short story “Once Upon a Time” by Nadine Gordimer. If an audio recording of the text is available, it may be offered to students to use for support. As students read, they should annotate the text by highlighting lines that specifically call attention to location (as well as barriers between locations). At the end of the story, readers should respond to the following guiding questions:

- What are the important locations in the story?

- How are these locations different from one another?

- Why are these separate locations important to the story?

Students may work independently to respond to these questions and then discuss their ideas in a small group before reporting out to the entire class. The teacher should direct the conversation for students to recognize that, by placing the events of the story in a segregated community, Gordimer is suggesting to the reader that xenophobia, paranoia, and segregation in the name of security have catastrophic consequences.

Activity 3

After discussing the story, students will work individually to create maps of the areas described in the story. Students’ maps should contain the following:

- Illustration of important sites in the community

- Illustration of barriers between the gated community and the rest of the world

- Caption summarizing what the map suggests (eight words or fewer)

After completing their maps, students should compose a short piece of writing that explains how the diagram and caption reflect underlying themes in the short story, including specific information from the text. This explanation, along with the map, should be added to students’ atlases.

Lesson Three: Beginning the Novel

This set of activities should take place as students begin reading Sing, Unburied, Sing.

Activity 1

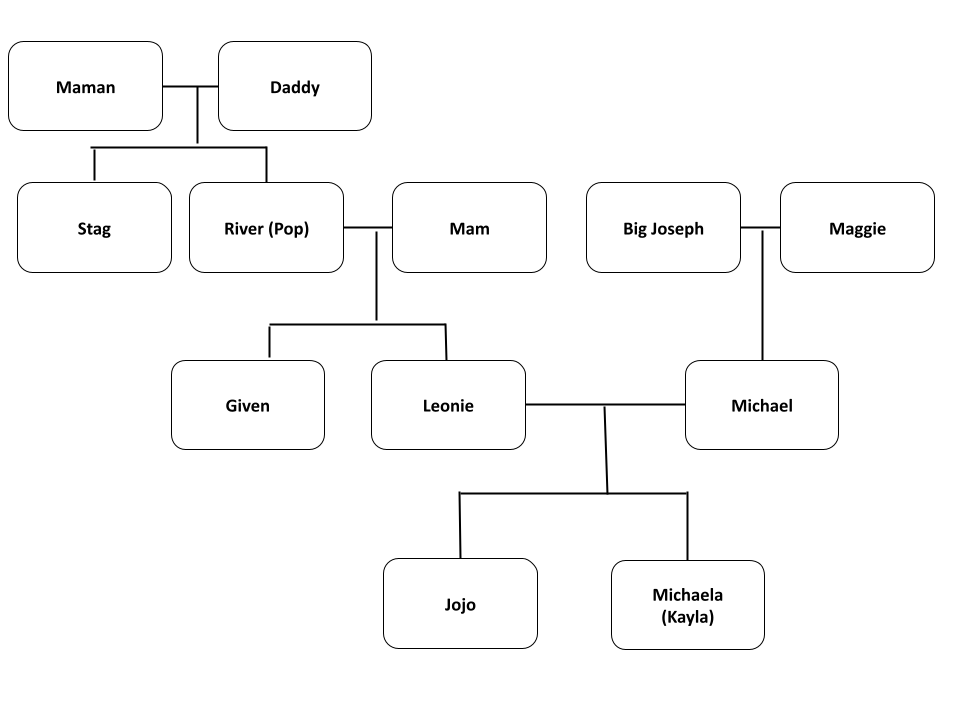

To introduce students to one of the kinds of maps that will be used in this unit, the teacher should display a family tree (either from their own life or based on a familiar text) and open a discussion: is this a map? Why or why not? The teacher should direct the conversation for students to recognize that a family tree functions as a map, because it illustrates connections between specific pieces of information of the same type. If time permits, each student should complete a family tree of their own (again, either based on their own lives or a familiar text).

Activity 2

The teacher will distribute two organizers for mapping important information in the novel: a family tree (see Figure 1) and a chart with three rows, labeled Present, Recent Past, and Distant Past. One or more names on the family tree diagram may be written in advance to give students a point of reference. The teacher should also clarify for students that a timeline is also a map, as it shows the relationship between selected pieces of the same kind of information (in this case, important events in the text).

Students will begin reading the novel together. The teacher may ask for a volunteer to read or play the first section of the audiobook (if available). After the first paragraph (ending in “Today’s my birthday”), readers will pause. The teacher will ask the students whether this part of the story is taking place in the past, present, or future, and how we, as readers, can tell. Students should recognize that, because the writing is in present tense, this part of the story is set in the present. The teacher should alert students to the fact that, when the verb tense changes, we should recognize that the novel’s timeline has shifted as well. It may be helpful to let students know that there are clues in the writing to tell the reader when the timeline changes: writing in the present tense indicates that the events are taking place in the present, events told in past tense are taking place in the recent past, and events told in past tense in italics are taking place in the distant past.

Activity 3

Students should continue reading on their own, or in small groups if desired. The teacher should clarify two objectives for readers as the progress through the first chapter:

- Add as many names to the family tree as possible

- Begin filling out the parallel timelines with important events on each row

If students finish before the end of the class period, they may share and discuss their responses on both organizers.

Figure 1: Sing, Unburied, Sing Family Tree (Completed)