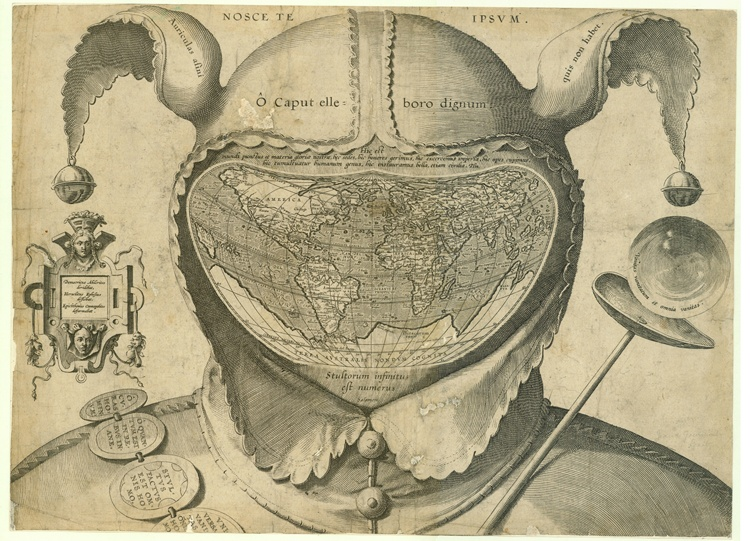

“Cordiform World Map in Fool’s Cap,” [Novacco MS 2F 6, https://www.newberry.org/file/1366]. Courtesy of the Newberry Library.

The anonymous Fool’s Cap Map, published sometime around 1590, shows the striking juxtaposition of a then state-of-the-art world map inside the motley hat of a court jester (or Fool). Entitled, “Nosce teipsum” – know yourself – the engraving evokes the merging of world and self as the map image becomes the figure’s face. We can only know the world through the self, it seems to suggest—or, alternatively, know the self through its connections in and with the world. More important, perhaps, it embeds the map itself—a now-iconic emblem of mathematical accuracy, empirical proof, and scientific method—into a deeply humanistic, allegorical, and moral matrix suggesting the inextricable relations between science and art.

This seminar took up the invitations to thinking, reflecting, representing and interpreting contained in this print, which was produced in the midst of the “cartographical revolution” of the sixteenth-century. Beginning with the premise that maps both create narratives and influence the shape and interpretation of texts, the participants considered how maps as historical objects offer narratives about how we imagine and organize ourselves in psychological, spiritual, social and political terms. But to get to this perspective, we had to interrogate our assumptions about what maps actually do. Are maps simply tools to help get from here to there, static forms of the ubiquitous GPS navigators we all use today? Are maps visual representations of places—or are they schematic and complex reflections on what we understand space and place to be? What sorts of objects count as maps: is a mood meter a map? Is an online data visualization a map? When are tattoos, tablets, sculptures and religious diagrams also best understood as maps? Taking our cue from J. L. Austin’s classic account of speech acts in How to do Things with Words, which argues that words can make things happen in the world, we asked how individuals, states, and cultures have “done things with maps,” and how, as teachers, we might “do things with maps” in the classroom.

Maps have become charged images in our ever-more visual world, codifying ideas and expectations about space, place, orientation and itinerary. “What is a map?” asks the map scholar and theorist Christian Jacob—and after famously spending 99 pages attempting a definition, he observes: “The map is a device that presents a new dimension, another degree of reality, within the field of vision…[it is] a widening of the visible field, of what can be thought and what can be uttered. It is also a space of anticipation, of predictability, of omniscience tied to the very fact of the synoptic gaze” (The Sovereign Map, 99). From this perspective, the term “map” usefully applies to a very wide range of objects from all over the world – as this seminar discovered, graphic organizers in classrooms are maps and so are the changing maps of the COVID pandemic; mappings of the self, like heart maps often used in elementary- and middle-school classrooms, coexist on a continuum with political maps which establish and contest territorial sovereignty. Maps have also existed across cultures in various forms, even though we (too often) assume that maps are a European invention in early modernity.

As the seminar traced the shifting intersections between cartographic technologies, social-political conflict, and literary form, we moved through themes in the history of cartography from the “cartographic revolution” of the sixteenth century to the grand digital-spatial dream of Google Earth. Participants grappled with the challenges of spatial literacy in verbal and visual texts, cartographic technologies and instruments, maps in books and as books (atlases), and textual uses of various mapping practices (spiritual, geographic, conceptual, data-driven). As the rich curriculum units designed by the participants show, we made ample use of online digital materials from the Beinecke Library, the David Rumsey Collection at Stanford, the Newberry Library, the British Library, and John Carter Brown Libraries.

The materials compiled in these units are wide-ranging—moving from mapping identities and the self through various literary texts to studying early twentieth-century genocides across the world and the history of African colonialism. Whatever their specific focus, each unit includes introductions to teaching with maps for various grades levels (seven through twelve), classroom exercises that teachers might use to integrate maps as thinking tools in their classrooms, and a variety of external resources that fellow teachers might draw on as they include maps in their pedagogy. It is worth noting the wide range of subjects in which maps could be incorporated, and though the focus here is largely on language arts and social studies, each unit also has ideas for how teachers in adjacent topic areas might adapt their strategies. The first three units in this volume focus on language arts, while the final two focus on social studies and history; the order moves from middle through high school grades.

William Wagoner, “A Cartography of the Self: Making Meaning of the World through Life Maps” develops strategies in “personal cartography” by shaping a year-long “Atlas of Experience,” a portfolio project that gathers together a series of student-generated “life-maps” which visually map student goals, learning, and growth throughout the year. Anchored in a study of Sandra Cisneros’s A House on Mango Street, the unit focuses on mapping as an interdisciplinary tool that facilitates critical thinking across literature and social-emotional curricula.

Sean Griffin’s “Mapping the Life and Times of Phineas Gage” engages the use of maps for travel and as reflections on travel. It builds on the teaching of John Fleishman’s Phineas Gage: A Gruesome, but True Story about Brain Science to draw together writing, literature, history and biology through the use of mapping. Following the journey of Gage through various maps—railway maps, brain maps, timelines, maps about literature—helps students integrate various aspects of a complex narrative, while also giving them tools for their own travel writing projects.

Aron Meyer’s “Distance, Location, and Movement in Sing, Unburied, Sing” shows how mapping as visualization becomes a generative tool for teaching literary analysis. Tackling the challenge of teaching Jesmyn Ward’s complex narrative to twelfth-graders, this unit suggests how rendering abstract concepts and multifaceted relationships in the novel as maps can enable students to become more confident and sophisticated readers, particularly with regard to topics such as race, trauma, identity and social stratification.

Robert Schwartz’s unit, “A Modern Scramble: Envisioning Colonialism in Africa using Maps and Literary Critique” aims to use maps to combine literary and historical topics in a unit that focuses on the European colonization of Africa in the late nineteenth century. Beginning with the division of the African continent among colonizing nations by drawing political boundaries on a map at the Treaty of Berlin, students are introduced to the history and legacy of colonization through a series of historical maps. They then turn to excerpts from Joseph Conrad’s classic novella Heart of Darkness, itself inspired by maps, and to Chinua Achebe’s searing critique of the work’s racism.

Mark Osenko shows how maps—both existing historical ones and analytical/exploratory cartographies generated by students—can illuminate a difficult subject: “Mapping Genocides of the Early Twentieth Century.” Deploying a variety of mapping techniques—territorial, resource and census mapping, as well as mind and emotional mapping—this unit develops strategies to help students learn about and critically reflect on global histories of genocide before the Holocaust.