It is important to provide a basic overview of New Haven’s early history prior to delving into an up-close examination of fences and underlying reasons for their need and use from a material culture perspective. Thus, snippet information should be provided concerning New Haven of old, complemented by an excursion to the New Haven Green and the New Haven Museum and Historical Society. Through the use of imagination and pictorial images made available at these sites, our children will visualize the New Haven landscape during the 17

th

, 18

th

and 19

th

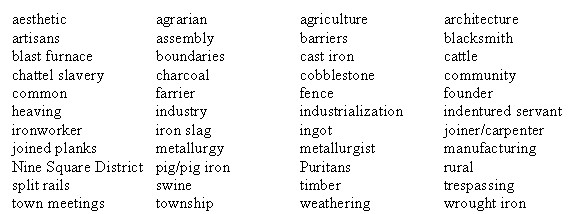

centuries. Introducing students to vocabulary that embraces our study is crucial to spark conceptualization; vocabulary to be embraced at each juncture includes-but is not limited to-the following word list. Students will be required to know the definitions of each of these newly introduced vocabulary words:

Related Excursions: Trip to the New Haven Green/Nine Square District, The Center Church, and Grove Street Cemetery; cameras required to photograph fences/gates.

Preliminary Brainstorming Activity

Based on information gathered during our excursions, students should begin contemplating why fences would have been a necessity during each specified century? Who would have needed to create them? Students working in groups of four will brainstorm possible explanations for their creation and will record their responses on the Ponder This Questionnaire form (see Worksheet 1, Attachment A). Responses will vary. Many young learners may immediately relate to use of fences in the 21

st

century, i.e., primarily as a source of protection, property ownership, and aesthetics. Taking into consideration snippets of early New Haven history that have been provided, however, students may speculate that fences were required to enclose animals, to connote ownership or boundaries, to enclose burial grounds, to show status, and more. The aim here is to get our students to get those thought processes going, to conceptualize the myriad need for fences. Post discussing their viewpoints in small groups and subsequently sharing their conjectures with the entire class, the following historical information can be reviewed.

New Haven Colony: The Formative Years

Prior to the arrival of Europeans during the 17

th

century, the New Haven colony was populated by the Quinnipiac-the aboriginal inhabitants of the region who resided and hunted in the lush woodland areas and fished along New Haven’s coastal regions. These Native Americans adapted to the verdant land. Working interactively with the environment, their communities dispersed and reassembled on a seasonal basis as social and ecological needs demanded. The Quinnipiac and other original indigenous inhabitants in the region, unlike their European counterparts, did not possess the concept of private land holdings. That viewpoint changed upon the arrival of Europeans.

1

17

th

Century Life

By 1638, Reverend John Davenport, a Puritan leader from England, the London merchant Theopholis Eaton, and approximately 500 Puritan followers settled in the New Haven region, a colony that stretched across what we today know as Stamford, Milford, Derby, East Haven, Branford, and Guilford. In time, these townships established their own political and economic governance, and eventually became independent communities. Abundant with woodland areas and what appeared to be fertile terrain, the New Haven colony was deemed a “new heaven” by many of its newcomers.

Eaton and Davenport played a major role in the city’s establishment: the two helped lay the plans for what we today refer to as the Nine Square District. They laid out a planned community with a large common in its center. A central meeting house was erected therein (where the Center Church stands today); it served as an essential gathering place for residents of the colony.

Residential areas comprised of a mixed economy surrounded the common. Initially, much of the land was used for agriculture. Farmers and their families raised corn, rye, hay, livestock, and more in the surrounding area. The common was used as pasture for cattle. Craftsmen, small shop artisans, and merchants involved in trade and commerce were also interspersed in the surrounding area. The New Haven community was predominately Eurocentric in composition.

2

Wood Fences: A Natural Evolution

Upon the Puritan inhabitants’ first arriving to this uncharted wilderness, they settled near New Haven’s shoreline. In time, the population increased; the colony’s residents moved further inland amid densely wooded areas. Land was cleared and cultivated. Ring-porous wood trees like oaks, chestnuts, and ash were chopped down in large numbers.

3

Timber was abundant. Farming communities and homesteads grew, and with it the increased use of this natural resource. Timber was not only used to create houses and other dwellings, but wood fences.

The use of easily split ring-porous trees made fence building an easy task: a row of stumps and large logs were set in place stacked in zigzagged formation resulting in a simple fence structures. Snake and rail fences were common. In time, sawn lumber was used to create picket-type and other structures. Simple or intricately designed, wooden fences lasted an average of six to eight years at best before having to be replaced.

Wooden fences were used to section off areas of the land for growing grain; to denote property ownership; and to serve as a warning sign and boundary for those indigenous inhabitants who first resided in the region. Using ring-porous wood for fence building proved useful for quick and easy replacement of deteriorated posts and rails. Should the need arise, farmers and their family members could get fence-making and fence repair jobs done themselves.

18

th

Century Life

The population of the New Haven colony remained homogenously Eurocentric during the 1700s. By 1784, approximately 3,500 people resided in the area. Puritans from England were the prevalent group, interspersed with a small number Anglicans, Protestants, Rogerenes (Quakers), and African slaves.

4

In time, the colony was comprised of societal classes of freemen or church members, free planters, indentured servants and apprentices, transient seamen, and wandering laborers-among them, a small number of free blacks. By 1786, the region we today call New Haven was incorporated into a municipality.

Farming and trade were major industries in the New Haven community. Huge ships were needed to transport sugar, rum, and other goods to the West Indies and abroad. More homes and buildings were needed for the ever-increasing population. Wood was also used as a major source of fuel-particularly for firewood and the manufacture of charcoal (which was also used by ironworkers in the manufacture of wrought iron products). Wood, therefore, was a much-required resource.

In time, the increased use of this natural resource resulted in deforestation. Farming communities continued to thrive. Wealthy communities grew. Fences continued to be a necessity-but for many farmers and landowners, they proved costly.

5

With the depletion of woodland areas in the immediate vicinity came the need to venture farther into the surrounding forest areas for timber. The need for transportation, fence restoration, and labor contributed to increased costs. Although wood was a viable resource for fence making, for many, an alternative barricade was sought. What resource could serve as a feasible alternative? Nature once again provided a solution.

Stone Fences: The Available Alternative

Deforestation produced a welcomed phenomenon. Farmers and other property owners discovered myriad stones of different shapes and sizes emerged from beneath the earth’s crust. Stones surfaced where land was cleared; seasonal changes-particularly heavy rains and cold winters-caused the ground to heave. The stones were so numerous that they had to be cleared from pastures and fields annually, a practice that sometimes occurred in the lives of farm owners for multiple generations.

6

The use of stone as an alternative fence-building material proved cost effective because of its abundance and availability. Clearing stones from the land, however, often proved a laborious task. Stones that dotted the terrain varied in weight and size and were often extremely heavy. Because of their weight, they were manually lugged or transported with assistance of oxen or draft horses. If lifted manually, stones were seldom hauled any further than necessary; many stone fences were constructed no taller than “thigh high” as a result.

Like their wooden counterparts, stone fences served many purposes: They were strategically stacked without mortar to create sturdy barricades. They were often used as boundary markers to deter trespassing or to demarcate property ownership. Stones were used to distinguish family plots and gravesites. They too were used for ecological purposes, to force rain to run along specific streams, to reroute small waterways, to drain the land, to enclose fertilizer, or isolate waste products. Stone fences were used to enclose livestock (although those who owned sheep and cows at times found it difficult to contain these farm animals, for they often climbed over and/or toppled the rocky barricades). Prosperous farm owners also used stone fences for aesthetic purposes and to connote wealth.

As held true for wood resources, stone fences battled time and elements of nature. Stone walls often crumbled with heavy rains or toppled because of herds of sheep butting into or crossing over them. Weather erosion also took its toll. Nevertheless, stone and wood fences could be found throughout the New Haven landscape.

19

th

Century Life

Related Excursion: Visit the New Haven Museum and Historical Society and Sterling Library; where applicable, view (and where possible make copies of) sketches and photos of the 17

th

, 18

th

, 19

th

, and 20

th

century landscapes.

With continued economic growth came increased change in the New Haven landscape.

7

By 1815, three churches were erected on what we today refer to as the New Haven Green. The former meeting house, where common folk and neighborhood leaders gathered, underwent reconstruction to become the Center Church. By 1821, the burial grounds that lie adjacent to the area were moved to a neighboring locale we today refer to as the Grove Street Cemetery. Thriving businesses, buildings, and new thoroughfares soon emerged and, with them, the demarcation of property. Shipbuilding and commerce heightened during the early 1800s, with much trade occurring between New Haven, the West Indies, other New England townships, and European shores. With this expansion came an influx of new European immigrants. By 1820, over 600 blacks resided in the community, many of them freemen. As of 1830, a little over 10,000 people resided in the city.

By the mid to late 1800s, businesses and manufacturing companies like the New Haven Clock Company, Sargeant and Company, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and the New Haven Carriage Company were up and running. Iron shops specializing in cast, wrought, and pig iron supplies increased, accommodating the needs of new businesses. New streets like Temple, George, High, Wall, and Orange were laid and new buildings erected. Iron railings and interrelated parts on bridges were built to replace wooden structures. By 1872, the New Haven Railroad was up and running. Park space was divided into residential properties; the need for new buildings and offices expanded because of the increased population. New Haven had become a thriving metropolis.

8

Cast Iron Fences - An Aesthetic Stance

Commercialization was in the forefront during the 19

th

century. Wealthy populations grew. Affluent communities broadened. Property ownership expanded. Agricultural communities were pushed to the outskirts of New Haven. The need for wooden fences to control and direct the grazing of cattle had disappeared. Former pastoral grounds in the center of town were transformed into an aesthetic backdrop to Yale College and surrounding edifices. Cast iron fences with horizontal rails were created to enclose land stretches that formerly served as pasture. The need for fences had once again evolved. They were used more so to demarcate property ownership and took on an aesthetic stance.

Many farmers and common folk complained that a cultural divide was taking place-that constituents of Yale College and others who amassed wealth were attempting to keep certain societal members beyond its realm. Although Yale constituents deemed the social occurrence unintentional, new metal fences for many connoted division between the well-to-do and everyday people.

Ironworks At A Glance

Ironworking existed in the New Haven colony as early as the 17

th

century. Individuals adept in ironwork manufactured pots and hardware. During the colony’s formative years, ironwork was done on a small scale by blacksmiths. These artisans used anvils, hammers, forge fires, wrought iron, and muscle to create metal objects. Wrought iron-a metal sometimes referred to as bar iron-was a malleable metal. It was created in bloomeries-types of furnaces used during that time period to smelt iron. Farriers used wrought iron for horseshoeing. Blacksmiths used it to repair imported ironwork, to create hardware (like nuts and bolts), and chains. Some smiths used it to create ornamental ironwork with complex shapes like those found in metal fences. They hammered and chiseled and filed it until it took on the desired finished form. For these artisans, working with wrought iron was more than an occupation; it was an art form.

Cast iron was also used during the early years. Cast (or pig) iron was made in blast furnaces. Melted at high temperatures, the liquefied iron was poured into molds and subsequently used to make everything from drinking vessels to railings to cannons. Unlike wrought iron, cast iron could not be shaped by hammering it. A skilled iron founder (one who makes iron castings) could, however, easily duplicate and mass produce objects using casting molds.

By the 19

th

century, industrialization had taken hold in New Haven, and with it the increased use of cast iron. This metal was used to create railroad tracks, metal wheels, railings for bridges, and more.

9

20

th

Century Life

Civic improvement in New Haven was on the forefront from the early 1900s to the First World War era. Community revitalization, preservation of the New Haven Green, development of parks and fine buildings, and cultural venues-ultimately creating the City Beautiful-was the collective focus.

10

Yale too played a part in the revitalization effort, for its School of Forestry was influential in improving condition of diseased trees and increasing their number throughout the city. The University opened its art gallery to the general public on Sunday afternoons. The college’s appreciation of art further extended to the community, for during the 1920s and 1930s, Yale contracted with Samuel Yellin to create intricately crafted gates and grilles for many of its campus sites. Among them were the wrought iron gates located at the Memorial Quadrangle, the Sculpture Hall Gate in the Yale Art Gallery, Harkness Tower on High Street, and the Sterling Library Manuscripts and Archives Room

11

.

Wrought Iron - The Artistic Comeback

Samuel Yellin was a master iron craftsman whose works were well known during this period. He stood firm on the belief that the use of wrought iron was not simply a craft, but an art form to be embraced and revered. Yellin worked out of a studio in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His intricately crafted designs heralded medieval-and-Renaissance-inspired European tradition. Yellin and his staff of approximately 200 craftsmen created gates, fences, and myriad iron-crafted objects. His contracted work stands as regally today as it did when it was first created during the early part of the 20th century. Samuel Yellin demanded meticulous work from those in his employ. Yellin’s work connects us with the spirit of New Haven’s past. Ironwork gates, fences, and grilles designed by this master artisan can be found throughout the Yale campus.

In a lecture he gave before the Architectural Club in Chicago, Illinois on March 9, 1926, he emphasized, “…[wrought iron] work should be done in the best possible manner. There is no other form of specification that the true craftsman understands. It has been said to me that all my workers must be artists, but many they are no different from other ironworkers, at least when they first come to my shop. But I always insist that all the work which leaves my shop should be honestly and beautifully executed… I am a staunch advocate of tradition in the matter of design.”

Samuel Yellin is to be lauded for his ironwork creations. He demanded the best of himself, and his artisans. Yellin’s Philadelphia staff consisted of immigrants from Italy, Poland, other European countries, and a minute number of ironworkers of African descent

12

. He allowed his workers to put a bit of themselves into their work. Although his product was impressive, it can be stated that he was not alone in his gate and fence creations.

Ironwork Artisans: An Omitted Reality

History often omits that major businesses, industries, and business owners often get sole credit for work created by people in their employ. This reality particularly holds true with regards to African Americans.

With this point in mind, we can look at iron fence work from a wide variety of viewpoints. A look at cast and wrought iron fences found throughout New Haven, for example, reveals myriad designs. Some herald French, Italian, and Romanesque influence. They too appear to contain designs common in West African culture.

13

To be taken into consideration when examining wrought iron fences is that many African slaves/artisans were transported from West Africa to American shores. Many of them hailed from such regions as Ghana, where the use of Adinkra symbols, animals and human images were used as a visual communicative form. Iron and woodcrafting artisans incorporated these images into their hand-crafted creations. Their artisan know-how was transferred and incorporated into the American framework without recompense or recognition. History does reveal, however, that the works of black artisans-particularly from South Carolina and Philadelphia-were shipped to other regions both within and outside of the United States. By the early 19

th

century, small establishments run by individual proprietors offered black artisans the opportunity to try out their ideas; this invitation was exclusive of the south, where ironmasters often blocked the free exchange of ideas between black artisans and entrepreneurs.

14

The key point is that the designs of black artisans could be recreated by other masters of the craft. It is, thus, imperative that teachers stimulate the minds of young learners to question diversity within the American framework, or the lack thereof (see Attachment D).