Julia M. Biagiarelli

First teach the children the meaning of the word

narrative

using a tool they are most likely familiar with, an online dictionary. Ask, "What is narrative writing?" After they give explanations that may or may not be correct, record the answers without telling them the actual meaning. Then, send a few students to the classroom computers and distribute dictionaries to the others to see how close they were to the official definitions.

Dictionary.com

defines the word

narrative

, originating between 1555 and 1565, in several ways: as a noun, "a story or account of events, experiences, or the like, whether true or fictitious." It is also, as an adjective, one definition stating, "representing stories or events pictorially or sculpturally:

narrative painting

."

5

With this definition in mind, students can be asked to look at an image and tell its story linking the use of images to the writing process.

From Reading and Speaking to Writing

Teaching the narrative writing process begins with reading or listening to someone else reading a narrative piece. Most children, by the time they have reached fourth grade, have heard and read many stories. After the dictionary lesson, hold story-telling sessions in which the teacher and the students have the opportunity to share their favorite stories. These stories can be from books, from their own personal experiences or even from television or movies. The purpose is to have students feel the flow of telling a story fluently.

Instructors can use their experiences with reading and listening as a starting point by choosing models from written works to teach each component and each step of the narrative-writing process. These introductory sessions are important to learning the writing process, and they are also important to building the confidence of the emerging writers. In my experience of teaching writing to children, I have found that when children feel comfortable with their knowledge and skills and when they feel safe and in positive relationships with their peers and their teachers, they will take the risk of revealing themselves through writing. Writing narratives involves a degree of exposure of a student's life experience, and often the most difficult groups to teach are not necessarily those who lack experience or skill, but those who lack trust, holding back their inner feelings from those whom they will share their writing.

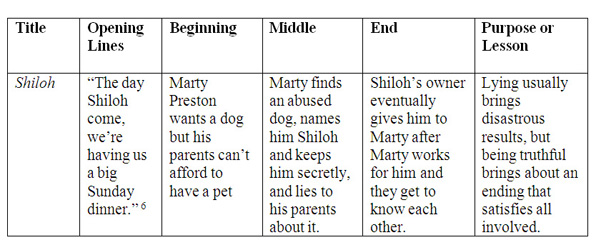

Once students are able to identify the parts of narrative works from reading them or hearing them read, they can begin to critique different pieces and hold peer discussions in which they share their preferences and experiences relating to the stories read. They can also begin practice writing by using the opening lines of their favorite stories to create a new middle and a new ending. Their understanding of the parts of the story can be displayed in a chart such as the one below:

Children who may have some difficulty or resistance to writing can practice the narrative form by telling a story into a recording device before writing it down. Gradually as these students work through the writing process, they can be weaned off the recording device and produce their work directly as writing.

Audience

The immediate audience for the children's writing will mainly be their teachers and their peers. Eventually they will write a narrative in the Direct Assessment of Writing in which the audience will be the people who score the test. However, the students can be motivated to imagine themselves as adult writers and decide who they would want to read their stories and why. Children can also ask themselves, "Would I want to read this story?" As they become more confident, they can also ask their peers the same question.

During the reading portion of the unit, the students can engage in discussion regarding the author's choice of audience by asking several questions: "Why did this author write books that fourth graders would read?" "What kind of people are these authors and what inspired them to write?" "How do these authors know that we, fourth graders, like reading their books?" "Do these authors have their own children?" "Have these authors ever been fourth-grade teachers?" As in any thought-provoking question-and-answer discussion group, one question will lead to another and often motivates students to write with enthusiasm.

Descriptive Writing

Another important component to creating a written piece that will be appreciated by readers is the ability of the author to describe people, scenery, feelings, and mood. Description creates images in the minds of the readers or reminds them of images stored in their own memories. A description may set the scene, as in this example from an account of my recent experience of entering a temporary space to teach while a new school building was being completed:

-

The bricks were certainly stacked upon each other in an orderly fashion, although

-

the mortar seemed to be 82% dust. Orb weaving spiders and carpenter ants were

-

living there happily despite the grayish, green water that was dripping through

-

multiple cracks. I turned the corner in the dim hallway and spotted room 207,

-

which was to be my classroom for the next nine months.

Description is best used in a story when the author pauses just long enough from the action to give details. Very long descriptions as well as those without enough sensory details can distance readers from the story line and lose their attention. In After the END Barry Lane quotes Carolyn Chute to bring this point across:

Writing is not writing skills, but knowing how to see. There are people who can't read or write who are novelists. They've got two lenses. Telephoto lens for big pictures and a lens a dentist would use. What they do to show the big picture is to use details they see with e small lens.

7

Balance among plot, description and character development will keep the readers reading. Teaching children description, as an enjoyable way to liven up their stories, is an excellent topic for a mini lesson.

Describing Character Development

Good stories have interesting characters, and a good description of characters includes their physical appearance, emotions, words, actions, and relationships with other characters. A new character being introduced into a story requires some description:

-

From where I was crouched in the corner, Roger looked nine feet tall and his

-

muscles were probably composed of concrete, but when he turned and smiled at me

-

I felt safe, calm and protected.

As the story progresses, these descriptions will change and evolve although they will continue to be related to the point being made by the author.

-

I'll never forget the earthquake that shook my kindergarten class, not just because

-

of the chaos, but because it was the beginning of my friendship with Roger.

Using Details, Adjectives and Names

Teaching the use of details can be a lesson disguised as a game. On chart paper or the board in front of the classroom, write a very bland sentence with a generic verb and a generic noun: for example,

The child walked into the room

. Students should be prepared to write either at desks or in a writing-circle group, and they should have writing utensils and notebooks ready. Meanwhile have another adult or a trustworthy student waiting just outside the classroom with a box of costume materials such as: hats, scarves, odd-looking shoes, colorful jackets and a few props. Send a student out of the door to be costumed and then instructed to enter the room making sure not to walk in a boring way. Tell students to copy down the boring model sentence and be prepared to write a more interesting one, using details and adjectives based on the person they see coming into the room. Some possible descriptions might be:

-

The tall, crazy boy rushed into the fourth-grade classroom tripping over a desk and

-

spilling all of the colored pencils off the art table.

-

-

With a sweet smile on her face, Rachel tiptoed into the secret attic room.

-

-

Looking lost and unhappy in the bright-green, oversized corduroy jacket, the ten-

-

year-old girl dragged her feet as she came into the room and cried, "I want to go

-

home."

After a few students have entered and sentences have been composed, it's time to share and give positive feedback. Then, as time allows, those who have been inspired after hearing what other students have written can have a chance to revise any sentences they are not happy with. If the entire lesson is presented on chart paper, the sentences produced can be posted in the classroom to motivate descriptive writing during other lessons.

Relating Images to Writing

Children usually pay a lot of attention to images by talking about them and relating their experiences to them. Autobiographical pieces that are coupled with images work well as models for children to imitate as they begin to create their own written works. A good example comes from

Seeing and Writing 4

, called

This is Daphne and those are her things

. Tujillo-Paumier presents a photo collage of some of Daphne's favorite personal items and a brief (fewer than 150 words) narrative from Daphne's life experience. Most of the items, although not all, relate directly to the narrative that describes Daphne's career path as a musician.

8

There are musical keyboards, string instruments, horns and the equipment to perform music electronically. Although Daphne is thirty-one-years old, and her life experiences are obviously more developed than a fourth grader's experiences, young readers may look up to her as a role model or relate to her by seeing that she reminds them of an older sibling, cousin, aunt, etc. A similar collage and narrative created by the instructor about the instructor or about a person closer in age to the students would also be a useful model. Once students have been presented with the model pieces and have been instructed on the components necessary to create their own stories, they can begin working on individual pieces.

To expand the image-writing connection for the next piece, the teacher can use a series of images of an autobiographical nature that are presented in sequential order, whereas in

This is Daphne and those are her things

, the images were presented randomly. Seeing the images presented sequentially will also model the formula for writing narrative pieces in the Direct Assessment of Writing on the Connecticut Mastery Test which requires that the student's piece have a clear beginning, middle and end.

9

The brief narratives modeled after

This is Daphne and those are her things

can then be separated into one-sentence or two-sentence ideas and used to create a graphic organizer in which the students elaborate on each idea separately. To complete the piece, they will then assemble these parts into a sequential narrative.

10

Expanding Points of View

Once students are comfortable with the autobiographical narrative form and have produced several adequate pieces, they can begin to write from other points of view. In an oral sharing group, the teacher can read or tell short fictional stories that involve two or more characters who are fourth graders. Have them identify the main character, whose point of view is emphasized in the story. Then have them identify the other characters and retell parts of the story from another character's point of view. After the students have been able to retell the narratives from different points of view, have them return to their own completed stories, so they can try to imagine the thoughts and feelings of another person in these narratives. I tried this exercise myself by imagining my story about Jean's death written from her daughter's point of view:

-

"Good riddens!" I thought as I hung up the phone. "It's about time that chain-

-

smoking, alcoholic finally died." My mother had been at the Nursing Home ten

-

miles away from me for eight years now and I could not see any reason why I

-

should visit her after all the pain and trouble she'd caused me.

-

-

Then I received another call. It was from a woman I'd never met. I think she might

-

be a nursing home volunteer or something. Apparently she has been visiting my

-

mother every Sunday for over a year now. I told her I didn't feel well and thanks

-

for being with my mother.

-

-

But, there was something gnawing inside me….

Then I imagined Jean's point of view:

-

"Oh why did I have children? They only break your heart. I'm so sorry I was such

-

a bad mother. Even if I could see them again, how would they know that I am so

-

sorry, I can't speak, and I can hardly open my eyes. Please, God, don't let me die

-

until I see Susan again…."

Writing from another point of view would also change the images that the students would choose and how those images would be arranged. Students can also be introduced to another tool from the toolbox, tone, by answering simple questions about the different feelings expressed by various points of view. Why does the story sound different from Susan's point of view? They can be taught to describe how the tone of the composition changes as the point of view changes

Revision

Creating a written composition, like any of work of art or science, involves practice and repetition. However, most fourth graders like to be finished with their work, as they hope to be free to have fun afterward. Convincing them of the joy of the writing process is another challenge for teachers. Barry Lane named his book about revision After THE END in honor of his experience with students who simply wrote "THE END" in uppercase letters at the bottom of the paper when they felt they had done enough work.

11

Lane mentions a seven-step writing process: brainstorm, map, free write, draft, revise clarify, edit. Then, he goes on to say that his seven-step process looks more like this: "revise, revise, revise, revise, revise, revise, and revise."

12

Knowing that adults and especially adults who are well-known artists, musicians, chorographers and published authors, revise throughout the creative process is the first step in opening young writers' minds to the idea that change is necessary as we write. Writing is not a math problem that gets solved and then it's done.

Because children are usually reluctant to change anything they produce creatively, the process of revising can be first practiced by the children with artwork done on an erasable surface such as a white board. Teachers can also show their students the steps taken by an artist as a work of visual art changes and reaches its final draft in a series of photographs. In addition, children can create a dance together by practice and repetition and revision until they are satisfied with the final product.

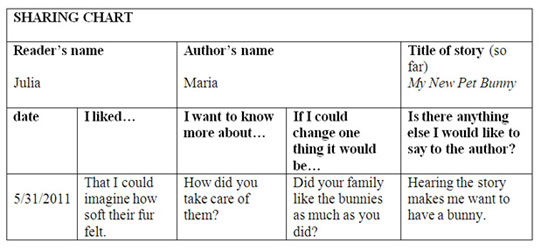

There is another factor to be considered when convincing young writers to learn to love revision. Children like to be seen, heard, and appreciated. Honoring their written work through each step of the process will encourage them to rewrite. This can be modeled by the teacher at first; and then, as the children become familiar with it, they too can contribute positive comments in sharing circles. Below, I've created a worksheet with easy-to-remember phrases that the students can learn to follow. It is a three-column chart with the following headings: "

I liked…, I want to know more about…, If I could change one thing it would be….

" At first the teacher will model the use of this chart in a group lesson after the children have listened to a peer's piece of writing, being careful not to use judgmental words such as right,

wrong, good

or

bad

. For future lessons, students will have this chart as a template ready for use when revising in conference sessions with the teacher and with peers. The goal for students is to be able to independently hold these honoring circles with their peers while the adults in the room are teaching other small groups of children. Below is the sample chart:

Editing

It is important to teach children that editing is different from revising. Both are important steps in the writing process. Often in classrooms editing and revising are lumped together, and little teaching happens. When students are told, "Find a partner and edit each other's work," the activity does not produce very effective results. Inexperienced writers will just guess or, worse yet, give incorrect editing advice. Editing is best done in small teacher-directed groups.

When

revision

is shown to students as

re-vision

and explained as seeing again, students are taught that they are taking another look at their work and making changes that will make the piece more appealing to readers, whereas editing can be described as "fixing" or "checking your work." Children often do not realize that editing is mainly for the mechanics of writing, such as the correction of grammar, spelling and punctuation errors.

As with all of the steps in the writing process, students will need to have the teacher model the editing and present mini lessons on editing techniques. In fourth grade children are expected know how to correctly capitalize, use end punctuation, use commas, use quotation marks, underline book titles and be able to distinguish between run-on sentences, sentence fragments and complete sentences. More advanced punctuation and editing, such as the use of colons, semicolons, use of italics, parenthesis, etc., can be directly applied by the teacher if needed.