Why use the graphic novel approach?

The graphic novel format has become more and more mainstream. Teachers have been using graphic novels in the class for students struggling with their reading skills. Graphic novels can be a great equalizer for students of different abilities. Special needs students find visual clues and emotional contexts that give them a better understanding of the written word. Visual interpretations of stories can be helpful to English Language Learners who are just beginning to acquire language skills. Graphic novels also have a way of drawing in reluctant readers, namely boys, who tend to be visual, and drawn to video games, computers, movies, and television. As a former Art Director for Grolier Books and Scholastic, I know this is a notoriously hard group to reach.

How did the graphic novel manage to make its way into libraries and schools?

Over the past decade libraries have been adding more books to the graphic novel sections. In most libraries graphic novels make up a small percentage of their collection of books. Cuyahoga County Public Library in Ohio for example counts 10% of their books as graphic novels but as much as 35% of the library’s circulation. These figures also hold true for school libraries as well. Yuma High School in Yuma, AZ, won the 2015 Will Eisner Graphic Novel Growth Grant. Yuma High School originally had a graphic novel collection that made up just 2.9% of their library’s collection but 31.76% of their circulation

1

. Graphic novels are even in high demand at institutions of higher learning. At Columbia University, Karen Green, the librarian of ancient and medieval history, selects graphic novels for Columbia’s library: “Graphic novels are the most frequently requested material in our Ivy League request system,” says Green.

2

High quality graphic novels such as Art Spiegelman’s

Maus

(1991) and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s

Watchmen

(1987) began to pave the way for the acceptance of graphic novels. Graphic novels started to become more acceptable in early 2000s. As publishers began to release classics in graphic novel form, books sales began to increase. This was spurred on by the popularity of the genre manga (Japanese comics).

In 2007 the first

Great Graphic Novels for Teens

list from Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) was released. This is a list of graphic novels and illustrated non-fiction books for children ages 12-18. The list helps young adult librarians make informed choices in terms of what they want to add to their library collections. Among the top ten titles for the 2016 list is

Drowned City: Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans

By Don Brown, a graphic novel that chronicles the events and devastation of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

In 2011 the American Library Association added an annually updated Core Collection of Graphic Novels for readers in grades K through 8. The ALA’s criteria and description reads:

Graphic novel here is defined as a full-length story told in paneled, sequential, graphic format. The list does not include book-length collections of comic strips, wordless picture books, or hybrid books that are a mixture of text and comics/graphics. The list includes classics as well as new titles that have been widely recommended and well-reviewed, and books that have popular appeal as well as critical acclaim.

3

Rationale: why combine Macbeth with the graphic novel form?

Why choose

Macbeth

for a graphic novel unit? When I questioned the English teachers at my school as to which play I should use, they most frequently recommended

Macbeth

followed by

Hamlet

. Other plays can be used, but I think it best to work with what is being taught within your school. This will reinforce what students are learning in English class.

Macbeth

gives the opportunity to deal with the seen and the unseen. This is an important question when illustrating a story. What will enhance the story? What should be left to the reader’s imagination?

Macbeth

deals with the super-natural, murder and intrigue. These topics present wonderful opportunities to deal with causes and effects - to introduce character motivation, atmosphere as a character, and other related concepts.

The Visual Elements of a Graphic Novel

Even though most students are familiar with the graphic novel format, students will need to understand the basics of building graphic novel panels. There is a basic visual vocabulary for the graphic novel, including, but not limited to, the following:

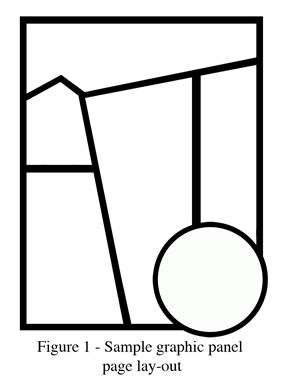

Panels:

Squares or rectangles that contain a single scene. It is a good idea to “break” these panels when appropriate. This can be as simple as a character’s head overlapping into another panel or as complicated as a character breaking out of the edge of a panel while running. Breaking the grid created by the panels creates a more dynamic layout. Figure 1.

Thought panel:

A thought panel has wavy lines as opposed to straight edges and contains images that represent thoughts or memories. Thought images are usually shown as monochromatic or duotone images. This helps to separate these images from what is going on in the story. Students should consider their colors wisely. Memories are never entirely clear in our minds; however happier memories may be rendered in brighter colors than bad memories. Yellow could be perceived as a happier color than a muted blue or brown. The color red might convey a more dramatic thought or memory.

Gutters:

the space between panels or the space at the center (binding) of the graphic novel.

Dialogue balloons:

contain the characters’ communications with each other. There are two different types of dialogue balloons: A rounded balloon for talking and a jagged balloon for yelling. Figures 2 and 3.

Captions:

contain information about a scene or characters.

Sound effects:

large words created outside of the dialogue balloons; for example, into the course of a sword fight the artist might insert words like “clang” and “thump.”

Thought balloons:

one large circle containing dialogue with a series of other circles leading to the character. Figure 4

Creating illustrations for graphic novel panels

In order to produce an effective scene, I find it is important to have students create multiple sketches of each panel. Quick sketches will give them the opportunity to work out the right composition of images, allowing them to see how their ideas might work out and which ideas work best. Would the viewer have an idea of what is going on in the scene without words? Will the illustrations assist the reader in understanding the play? Are characters conveying the right emotions - emotions that support your interpretation? It is important to make sure the story and the visual images are working together to convey the emotion and the plot of the story.

Decisions will also need to be made as to the language of the graphic novel. Some of the graphic novels based on classics alter their language to make it more modern and easier for the reader. In my classes, this issue will have to be a personal choice based on student needs, but I think it is a good idea to stick to the original language when possible. If you, the teacher, are lucky enough to be able to collaborate with an English teacher who is teaching

Macbeth

the burden of such decisions should be lessened. Provided you do have English Language Learners or students who are struggling with reading, it would be a good idea to modify effectively.

My classes are not leveled. My students come to my classroom with a wide range of skill sets. At a magnet school there is also the unique situation of students coming from various school systems. What was expected from a student during their k-8 education varies widely. The majority of students come from the New Haven school system. We also have a mix of student from various suburban school as well as private schools.

Students would also need to choose if the story will be reset in time. Would it be helpful to set the characters in a more modern context? Would setting the characters in a more modern setting make it easier for students to relate to the story? This is not unusual for both movie and theater productions of Shakespeare’s work. Whether students choose the 11th century or the 21st, some aspects of the time period would need to be researched. Choosing a color palette to work with is also important. To a certain extent colors will be dictated by the time period, setting and mood of the story.

There is an excellent example of a

Macbeth

graphic novel by John Haward. This can be used as reference for the visual arts teacher, though I think exposure to those images might influence students too much. It has an effective use of color and composition both in terms of individual panels and overall page layout. The color palette shows a dark stormy Scotland while also using bright colors to draw in the reader. The construction of panels within the page make for a dynamic page layout and help lead the viewer through the action

I would show students

Romeo and Juliet by

John McDonald (Adapter), William Shakespeare (Author) and Clive Bryant (Editor) to show the basics of a graphic novel. (Kindle edition and could be projected on screen.) Most students have a basic idea of what happens in

Romeo and Juliet

. There are, visually, wonderful sword fights and examples of the overall vocabulary of the graphic novel. The illustrator also deals well with Juliet’s death scene. She is shown in silhouette, which is something most students would not expect. I would keep borrowings to a minimum, so that imitation is not overly encouraged though students’ sense of a range of possibilities would be increased. Students will come to the project with various levels of prior knowledge of both the play and the graphic novel form.

For visual reference there is also the possibility of showing book illustrators from the golden era of illustration. These illustrations are not similar in style to the graphic novel, but they do serve the same purpose. N.C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle and Maxfield Parrish illustrations are all excellent examples of illustrators who worked to create images that enhanced the story. N.C. Wyeth’s work in particular shows examples of illustrating the right moment in the action. Scribners reissued a number of classic illustrated books by these illustrators. Titles include:

The Scottish Chiefs

by Jane Porter,

The Boy’s Kin

g

Arthur

by Sidney Lanier and

The Arabian Nights

edited by Kate Douglas Wiggin and Nora A. Smith.

I find it important to provide students with plenty of access to reference materials. There are excellent resource books used by professional illustrators.

The MacMillian Visual Dictionary

by Jean-Claude Corbeil and Ariane Archambault provides reference for over 3,500 different objects. Pictures include everything from street lights to buildings to various styles of clothing. There is also

Facial Expressions: A Visual Reference for Artists

by Mark Simon. This book has over 250 pages of different faces showing different emotions from various angles. This can be helpful in finding the right emotion for a character’s face.

Google or Bing images are good resources. However if a student’s search is not specific enough I find it can be time consuming. It is well known that illustrators (N.C. Wyeth and Norman Rockwell) used real life models. I have let students use other students for models and to pose for a reference photograph.

Students who are struggling with their drawing skills can set-up scenes and photograph them and work over them. Most students have phones with cameras. They can then import those pictures into Photoshop. Photoshop works on a system of layers. Black line might make up one layer while color would be on another layer. Thought and type bubbles would also be on one layer. This allows for easier editing of lines, colors and the positioning of both type and graphics.

Students sometimes tell me they feel as though they are “cheating” if they are working over a photograph. Audrey Flack (Super Realism) was known to have set-up still life scenes and photographed them for her work. She would then turn these photos into slides and project them onto the canvas and paint over the projection, similar to camera obscura.

4

Camera obscura was used as drawing tool by artists during the Renaissance.

Macbeth: Act II scene i lines 1-30 and summary

Sometime after midnight, just before Macbeth murders Duncan, Banquo and his son Fleance return to Macbeth’s castle. Banquo is weary, but he somehow cannot sleep. Macbeth unwillingly encounters Banquo and his son. Banquo seems surprised to see Macbeth is still awake. He hints that Macbeth should be asleep. Banquo points out that King Duncan has enjoyed Macbeth’s hospitality. He gives Macbeth a diamond, presumably a gift from Duncan to Lady Macbeth as a thank you for her hospitality. When Banquo references the witches’ prophecy, Macbeth replies he and Banquo will “speak further” at a later time. Macbeth and Banquo part ways.

Enter BANQUO, and FLEANCE bearing a torch before him

BANQUO

How goes the night, boy?

FLEANCE

The moon is down; I have not heard the clock.

BANQUO

And she goes down at twelve.

FLEANCE

I take’t, ‘tis later, sir.

BANQUO

Hold, take my sword. There’s husbandry in heaven;

Their candles are all out. Take thee that too.

A heavy summons lies like lead upon me,

And yet I would not sleep: merciful powers,

Restrain in me the cursed thoughts that nature

Gives way to in repose!

Enter MACBETH, and a Servant with a torch

Give me my sword.

Who’s there?

MACBETH

A friend.

BANQUO

What, sir, not yet at rest? The king’s a-bed:

He hath been in unusual pleasure, and

Sent forth great largess to your offices.

This diamond he greets your wife withal,

By the name of most kind hostess; and shut up

In measureless content.

MACBETH

Being unprepared,

Our will became the servant to defect;

Which else should free have wrought.

BANQUO

All’s well.

I dreamt last night of the three weird sisters:

To you they have show’d some truth.

MACBETH

I think not of them:

Yet, when we can entreat an hour to serve,

We would spend it in some words upon that business,

If you would grant the time.

BANQUO

At your kind’st leisure.

MACBETH

If you shall cleave to my consent, when ‘tis,

It shall make honour for you.

BANQUO

So I lose none

In seeking to augment it, but still keep

My bosom franchised and allegiance clear,

I shall be counsell’d.

MACBETH

Good repose the while!

BANQUO

Thanks, sir: the like to you!

Exeunt BANQUO and FLEANCE

The main question here would be what Banquo is trying to convey to Macbeth, and how Macbeth receives Banquo’s words. Students should ask themselves questions such as: What does each character say to the other? What is hinted? What is hidden? Why? Banquo comments on the night being without light: “There’s husbandry in heaven; Their candles are all out.” What is Banquo feeling or sensing? Does he sense that something is about to happen? Does he show this fear or concern in his facial expressions or mannerisms? How does the darkness act a force of evil, is the lack of “candles” (stars) in the heavens a premonition of something terrible to come. Can the darkness, visually, become its own character in the graphic panels? If so, who is more visually enveloped in the darkness, Banquo or Macbeth? Banquo talks about being troubled by his dreams, by the witches prophecies. Does Macbeth share Banquo’s concerns? When Banquo says “I dreamt last night of the three weird sisters: To you they have show’d some truth.” Macbeth responds “I think not of them:” What would Macbeth’s facial expressions look like compared to Banquo’s? Should Macbeth’s facial expressions hint at what he is hiding? In terms of body language, should Macbeth have his back to Banquo, so that only the reader knows what Macbeth is really thinking? Students should be looking at each character’s perspective.

Students would also need to address why Banquo feels the need to point out King Duncan’s finer points, his kindness and generosity, Duncan’s gifts to the household staff and his gift of a diamond to Lady Macbeth. What might Banquo being trying to convey to Macbeth?

Macbeth: Act II scene i lines 33-64 and summary

Macbeth is anticipating Lady Macbeth’s signal, a bell, as he moves closer to King Duncan’s chambers. He is increasingly thinking about murdering the king and he is trying to prepare himself for the act. An imaginary dagger floats in front of him, leading him toward Duncan. Macbeth begins to question the appearance of the dagger, he reaches out to grab it, but nothing is there. He even draws a real dagger from his belt and holds it up for comparison. The seen and the unseen, reality and imagination, are side by side. The dagger changes, becoming bloody, and Macbeth begins to think more murderous, predatory thoughts as shown through animal and mythological images and references. He hears the bell, and responds: “Hear it not, Duncan, for it is a knell which summons you to heaven, or to hell.”

MACBETH

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

Thou marshall’st me the way that I was going;

And such an instrument I was to use.

Mine eyes are made the fools o’ the other senses,

Or else worth all the rest; I see thee still,

And on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood,

Which was not so before. There’s no such thing:

It is the bloody business which informs

Thus to mine eyes. Now o’er the one halfworld

Nature seems dead, and wicked dreams abuse

The curtain’d sleep; witchcraft celebrates

Pale Hecate’s offerings, and wither’d murder,

Alarum’d by his sentinel, the wolf,

Whose howl’s his watch, thus with his stealthy pace.

With Tarquin’s ravishing strides, towards his design

Moves like a ghost. Thou sure and firm-set earth,

Hear not my steps, which way they walk, for fear

Thy very stones prate of my whereabout,

And take the present horror from the time,

Which now suits with it. Whiles I threat, he lives:

Words to the heat of deeds too cold breath gives.

A bell rings

I go, and it is done; the bell invites me.

Hear it not, Duncan; for it is a knell

That summons thee to heaven or to hell.

Exit

What visual questions might arise from Macbeth: Act II scene i

The focus of this scene should be on Macbeth’s internal process. This is his final submission to his murderous thoughts and to the act of murder itself. The visual questions revolve around how to interpret this powerful scene. The choices will come down to focus: Is Macbeth’s tipping point caused by external forces - the night, the influence of his wife, the witches prophecies and more immediately, the dagger? The dagger seems so real that Macbeth actually attempts to grab it, what kind of atmosphere might be swirling around him. How might students make the illustrations take on an “other-worldly” appearance, by using the background as character?

Would the scene focus on Macbeth’s internal influences? Should the dagger be shown at all or should it be assumed that this is just a product of Macbeth’s “heat-oppressed brain?” What would someone in Macbeth’s state of mind look like in terms of his facial expressions and mannerisms. Thought panels could be used to show what’s going on in Macbeth’s mind. What images, drawing on the text, might show such a troubled mind? Macbeth is on the verge of irrevocably changing his course in life; how might that play out visually in his thoughts?

Macbeth: Act IV scene iii lines 84 to 99 and summary

Malcolm is testing Macduff to find out where Macduff’s loyalties lie and how he feels about Macbeth. Malcolm and Macduff have come to England to join with the English and to depose Macbeth. Macduff has left his family behind, making Malcolm wonder if Macduff is in league with Macbeth. Malcolm, the rightful king, tests Macduff, telling Macduff what a horrible king he himself would make, an even more ruthless ruler than Macbeth. He says that he sees in himself “

All the particulars of vice so grafted That, when they shall be open’d, black Macbeth Will seem as pure as snow”

MALCOLM

I grant him bloody,

Luxurious, avaricious, false, deceitful,

Sudden, malicious, smacking of every sin

That has a name: but there’s no bottom, none,

In my voluptuousness: your wives, your daughters,

Your matrons and your maids, could not fill up

The cistern of my lust.

MACDUFF

Boundless intemperance

In nature is a tyranny; it hath been

The untimely emptying of the happy throne

And fall of many kings. But fear not yet

To take upon you what is yours: you may

Convey your pleasures in a spacious plenty,

And yet seem cold, the time you may so hoodwink.

We have willing dames enough: there cannot be

That vulture in you, to devour so many

As will to greatness dedicate themselves,

Finding it so inclined.

MALCOLM

With this there grows

In my most ill-composed affection such

A stanchless avarice that, were I king,

I should cut off the nobles for their lands,

Desire his jewels and this other’s house:

And my more-having would be as a sauce

To make me hunger more; that I should forge

Quarrels unjust against the good and loyal,

Destroying them for wealth.

MACDUFF

This avarice

Sticks deeper, grows with more pernicious root

Than summer-seeming lust, and it hath been

The sword of our slain kings: yet do not fear;

Scotland hath foisons to fill up your will.

Of your mere own: all these are portable,

With other graces weigh’d.

MALCOLM

But I have none: the king-becoming graces,

As justice, verity, temperance, stableness,

Bounty, perseverance, mercy, lowliness,

Devotion, patience, courage, fortitude,

I have no relish of them, but abound

In the division of each several crime,

Acting it many ways. Nay, had I power, I should

Pour the sweet milk of concord into hell,

Uproar the universal peace, confound

All unity on earth.

Students would need to decide whether to confine their visuals to Malcolm talking to a horrified Macduff or whether to draw what Malcolm is inventing. If the latter, the question would arise: How symbolically should lechery and avarice be represented? And a second, harder question: How might students convince the viewer, visually, that Malcolm is painting a false picture of himself?

Silhouetted characters in the foreground with the action in the background is one way to give the impression of a story being told. This technique could be useful in showing Malcolm’s agenda, and Macduff’s reactions: Would the student show what Macduff thinks as Malcolm is speaking?

Would Macduff look on as scenes of Malcolm’s horrifying behavior enters his mind? Could Malcolm’s temptations be shown in thought panels in a monochromatic or duotone color scheme? Should Malcolm’s long list of horrible deeds be implied, for example showing some beautiful women in a thought panel in reference to Malcolm’s thoughts of lecherous behavior? Would it be a good idea to show Malcolm’s face in the foreground talking about the horrible king he would be with Macduff’s horrified face in the background? What would Malcolm’s face look like during the exchange? Would he let the audience in on his trickery - his test for Macduff? Considerations such as these are what will influence the viewer in the final product.

Macbeth: Act V scene iii lines 37 to 62 and summary

The doctor has come to report to Macbeth on Lady Macbeth’s condition. Lady Macbeth is so troubled by what she and her husband have done that she cannot sleep. Instead, she sleepwalks, reliving as she does the terrible events that have transpired. The doctor is trying to tell Macbeth that there is no cure because the cause is spiritual and metaphysical, and that only Lady Macbeth can cure herself.

Macbeth:

How does your patient, doctor?

Doctor:

Not so sick, my lord,

As she is troubled with thick coming fancies,

That keep her from her rest.

Macbeth:

Cure her of that.

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased,

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow,

Raze out the written troubles of the brain

And with some sweet oblivious antidote

Cleanse the stuff’d bosom of that perilous stuff

Which weighs upon the heart?

Doctor:

Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

Macbeth:

Throw physic to the dogs; I’ll none of it.

Come, put mine armour on; give me my staff.

Seyton, send out. Doctor, the thanes fly from me.

Come, sir, dispatch. If thou couldst, doctor, cast

The water of my land, find her disease,

And purge it to a sound and pristine health,

I would applaud thee to the very echo,

That should applaud again.--Pull’t off, I say.--

What rhubarb, cyme, or what purgative drug,

Would scour these English hence? Hear’st thou of them?

Doctor:

Ay, my good lord; your royal preparation

Makes us hear something.

Macbeth:

Bring it after me.

I will not be afraid of death and bane,

Till Birnam forest come to Dunsinane.

Doctor:

[

Aside

] Were I from Dunsinane away and clear,

Profit again should hardly draw me here.

Exeunt

.

Should thought panels be used to convey Lady Macbeth’s condition, and Macbeth’s processing of the doctor’s news? What color would convey that type of madness? Would Macbeth be staring at the doctor intently to find out what the prognosis is or would he be too focused on what is to come? Is he pleading, or angry, or does he feel the situation with Lady Macbeth is too far gone at this point? Is it all he can do to hold himself together? Does Macbeth seem to be rushing towards his own destiny?

How would the students dramatize this scene? If Macbeth were in the foreground, what emotions should his face convey to the reader? How would the doctor be reacting in the background? Is the doctor in an impossible situation? Student might choose to show the doctor in the foreground reacting to Macbeth’s behavior in the background.