Caitlin M. Dillon

When we look at a picture, even if we study it well, we cannot perfectly recreate it in our mind's eye later on. Similarly, when we are exposed to language, we generally do not remember the content word for word or line for line.

2

Nevertheless, we may say that we do remember a picture or a text that we have viewed or read. When we remember images and texts, what is that we remember? Cognitive scientists study this topic, and they say that when we view images or read texts, we construct mental representations of them.

3

The representations themselves are abstract recordings of the characteristics of the image or the meaning of the text. The images we view can be real, dynamic ones of world around us or static ones such as paintings; for either type, we construct representations that we organize into models or frameworks.

As we acquire mental representations of various aspects of the world through our interaction with the people and things around us, we organize these mental representations into various kinds of mental models relevant to the recurring experiences we have.

4

For example, children who experience the same series of dynamic images (and sounds) every night when being put to bed develop a mental model that could be called a bedtime model. This bedtime model might consist of a parent pulling a book from the shelf, turning the pages as he or she talks, putting the book down, turning on a mobile, and turning out the light. When the child has internalized this series of events or formed a mental model for the bedtime routine, then he or she will be surprised if the bedtime routine is not followed one night. A mental model can be thought of as a set of expectations in a given circumstance.

Similarly, as children gain experience with narrative text (stories), they develop models based on their generalized understanding of the typical structure of stories.

5

With exposure to stories, children develop mental models for narrative texts.

6

They build a mental model that contains the expected elements of a story. The kind of mental model that we form while reading a given text is called by a specific name: the situation model.

7

The situation model includes not representations of the exact content of what was read (i.e., it is not a word--for--word or pixel--by--pixel recorder), but representations of the meaning we gleaned from the text, and it incorporates connections that we make to prior knowledge and our pre--conceived understandings of the world.

8

The situation model can be thought of as a mental model that has been filled in with the details of a particular story.

Children progress through several stages of development regarding the complexity of the mental models they build for the structure of narrative texts.

9

Although the general components of stories remain consistent across different examples and over time, children's awareness of that structure becomes increasingly organized and detailed over time. Children (and adults) use the experiences they have had building situation models to create increasingly elaborate mental models, into which they can fit more details and more information about the story, a process that allows for improved comprehension and retention of the stories.

Mary Ellen Moreau has developed a series of tools to help teach children the structure of stories. She follows a progression that most children go through naturally as their mental models for stories become more elaborate. Early in narrative development, children's mental models for narrative text are quite simple, consisting of a character in a setting; this is the "Descriptive" stage.

10

When children are in this Descriptive stage, they will tend to mention and possibly describe the main character(s) and the setting when retelling a story. In the next stage, Action Sequence, children tend to include in their retellings the character(s) and setting and a list of actions that occurred in the story. At this stage, the actions are not necessarily in chronological order, and the story as retold by the child may not be comprehensible to a listener. Later in development within this stage, retellings include actions in the order in which they happened in the story.

When children begin including in their retellings the idea that the characters faced a "kick--off"

11

(often a problem) that led to the actions in the story, then they have reached the next stage of narrative development, the Reactive Sequence. At this stage, the actions of a story are not simply events but are characters' reactions to a problem or unusual situation. In the following stage, Abbreviated Episode, children express the characters' reactions as consequences of their feelings about the kick--off. Children who are in the Abbreviated Episode stage have built a mental model consistent with their (subconscious) expectation that narrative texts include explicit or implicit information about character(s) and setting early on in the story, then about a kick--off that causes an emotional response in the main character, whose subsequent actions are a result of those feelings. A story told by a child in the Abbreviated Episode stage could be something as simple as, "I was in the sandbox and I got mad at Caitlin because she took my shovel. I hit her." In this example, the main character is the child telling the story, the setting is the sandbox, the kick--off is Caitlin taking the shovel, the character's feeling in response to the kick--off is "mad," and the character's subsequent reaction is hitting Caitlin.

Mary Ellen Moreau's stages of narrative development continue with the Complete Episode, the Complex Episode, and the Interactive Episode.

12

They do not need to be described here in more detail; at the basic level these stages are consistent with the idea that we form situations models as we listen to or read stories and continue to use them to build an increasingly complex mental model for stories. When readers (or listeners) come to new content, they integrate that new information into their current situation model. Readers who have more prior knowledge are able to integrate new information more completely and to retain it for longer periods of time compared to readers with less prior knowledge.

13

Readers' comprehension may therefore be inhibited if they do not have adequate models prior to reading, or if they do not fill in their situation model appropriately as they read. The meaning--based representations with which we fill in the situation models are what we remember later -- even though we do not retain the precise text, we retain the representations of the text's meaning.

14

Furthermore, our situation model for a particular text can contribute to the expansion or refining of our mental model for narrative texts so that we are better equipped to face new narrative texts in the future.

Thus far, the examples discussed have included mental models for a bedtime routine and for the structure of narrative texts. Mental models, however, can be formed for many encounters we have with the world. Abigail Housen does not use the term mental model in the reports of her research findings that I have read; nevertheless, it seems that her method of teaching students to observe and think about visual images could be described as a method of helping students develop increasingly sophisticated mental models for observing visual images. Housen and others have developed a method, called Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), designed to help children (and adults) observe visual images in an increasingly detailed and informed manner such that they also develop increasingly sharp critical thinking skills, which have been shown to transfer to settings other than those in which they were taught.

15

Housen found that when children are given practice interacting with each other while viewing artwork, they develop improved critical thinking skills more quickly than children who are not given these guided opportunities to explore visually presented works of art.

16

The visual modality is used as a starting point for group discussion, allowing students to develop skills that transfer from the group setting to a one--on--one setting and that eventually transfer to other contexts, such as those involving non--art objects. For instance, Doley, Friedlaender, and Braverman

17

found that first--year medical students who participated in training involving discussions of paintings (using an approach similar to VTS) developed better visual observation skills than their classmates who did not participate. The observational skills -- developed using paintings --could be tranferred to other types of images, so that the participating students were able to make more precise observations and inferences regarding pictures of skin lesions and other medical visual images.

Further transfer to literacy skills also appears to result from students' long--term participation in VTS, as evidenced by the results of the Minnesota State Reading Test taken by eighth--graders each year from 1996 through 2000. Housen and her colleagues worked with teachers in a Minnesota school, Byron, to help them implement VTS beginning in 1993. The first group of Byron students who began participating in VTS in 1993 became eighth--graders in 1998, the second group in 1999, and the third group in 2000. Before 1998, Byron eighth--graders had not received VTS training. The results of the Minnesota State Reading Test were the following: from 1996 through 2000, the average percent of eighth--graders in schools other than Byron who passed the test increased steadily from approximately 60% to 80%. A control school tracked by Housen and her colleagues followed this pattern. In contrast, the average percent of passing Byron eighth--graders increased from approximately 50% and 54% in 1996 and 1997 (before VTS training) to approximately 77%, 80%, and 87% in 1998--2000 (after VTS training). Housen states that, "The Byron school principal, teachers and school board members believed that the school district's participation in the five--year pilot program of VTS, contributed significantly to Byron's placement in the top 8 percent of Minnesota schools."

18

The results of a study by psychologist Joseph Anderson, as reported in his 1974 article, are consistent with the idea that we are able to construct representations for visual stimuli more efficiently than we are able to construct representations for verbal (text) stimuli.

19

He explained that as a group, children displayed varying levels of ability to reproduce given stimuli depending on the modalities of input and output: they performed best in the visual input--visual output condition, then the visual input--verbal output and verbal input--visual output conditions, and finally the verbal input--verbal output condition. The author of this study hypothesized that children performed most poorly in the verbal--verbal condition because it required internal translation of the verbal input into a visual representation and then back to the verbal modality for output. Thus, in my unit, I plan to focus on visual stimuli (images) as a means of helping my students form mental models, even though I am ultimately interested in the students' having improved text comprehension and retention.

Because we are able to form more detailed mental representations if we have already developed a mental framework, or mental model, of the characteristics of the image, it seems that the key to helping my students use visualization skills to build better memory and comprehension is to help them develop mental models. Mental models, even when developed using images, can also be used to retain information and details gleaned from a text.

Assessment

Following Wiggins and McTighe,

20

I begin my unit with the assessment I am planning to use, in order to ensure that the lessons contribute directly to the development of the skills to be fostered. In the present unit, the assessment would consist of a pre--test and a post--test to be administered before starting the unit and after the lessons have been completed. The assessment allows the teacher to determine the extent to which the lessons have helped meet the unit objectives; at least for the pre--test, I would choose not to assign grades based on quality as measured by the rubric.

The assessment includes two parts each of which includes a brief discussion prior to having the students write a response. The first part is a response to a visual image, and the second part is a response to a poem. During the pre--test, I would use chart paper to keep notes about the pre--writing discussion; then during the post--test, the same notes could be used as a brief review of the original discussion before the students begin to write. The specific format of the assessment could be adapted or adjusted to match various student levels and teacher goals, but the basic idea could be the following:

To assess the extent to which students make observations of an image and use those observations to support a claim:

-

(1) Prior to starting the unit, students bring in images of homes: indoor or outdoor images of any part of homes from any time period or location, real or imaginary, in photos or drawings or other media. I would ask the students to try especially to bring in images of living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms. Have a discussion about the difference between a "home" and a "house," about what makes a home a home rather than a house, or about the meaning of "Home is Where the Heart Is."

-

-

(2) Pre--test: Give the students ten to fifteen minutes to write their answer to a question such as:

-

--Which image is a good illustration of the saying, "Home is Where the Heart Is"?

-

--Which image would you be most likely to call home?

-

--Which image is a superb example of a "home" rather than a "house"?

-

--Which image would [a character from a class reading] most likely call home?

-

--After students have answered one of the questions above, have them answer the following: Why? Provide evidence based on your observations of the image. At least three specific observations of the image should be included in your response.

-

-

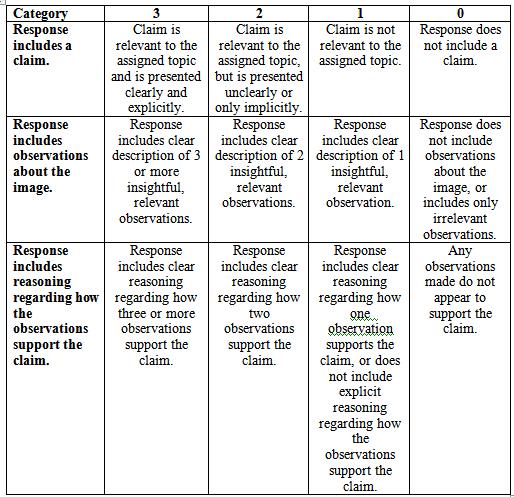

(3) Using a rubric similar to the one shown as Table 1, the teacher scores each response. The rubric includes categories directly relevant to the present unit; additional categories covering organization or usage could be added.

-

-

(4) Post--test: The post--test could be a revision of the student's own original response, a second response to the original pre--test question (without looking back at the first response, but using the same images), or the students could choose a new question and write from scratch; regardless of the assignment, the amount and quality of evidence provided could still be compared to the pre--test response if the same rubric is used to score both the pre--test and the post--test.

Table 1. Sample rubric to be used in scoring the visual image pre-- and post--assessments.

A claim in a response would simply be a statement such as, "I believe that the image of the girls' blue bedroom is a superb example of the saying, 'Home is Where the Heart Is.'" Observations made in support of this claim could include statements such as, "The girls whose bedroom this is appears to have made it their home using images of things they love, such as the photo of themselves playing with a golden retriever in a colorful heart--shaped frame, placed centrally on the night--table between their beds." An explicit statement describing how the framed photo supports the claim could express the idea that the placement of a photo of a beloved pet in a vibrant frame and in a prominent position where they would see it at the beginning and end of the day is a way of making their bedroom a home because it is an image of a loving relationship in their lives, and it represents a personal attachment they have made in the world. Students might express this idea with a sentence such as, "The girls made their room feel like their own place by putting a picture of their dog by their beds."

To assess the extent to which students make observations of a text and use those observations to support a claim:

-

(1) Read as a class the poem "Where I'm From" by George Ella Lyon. In a brief discussion, lead the students to see that each line (or pair of lines) of the poem tells a story and reveals something about the poet. An example to give to the class could be the lines, "I am from the dirt under the back porch. (Black, glistening, it tasted like beets.)" These lines tell us not only about the poet's house, but also that at some point in her youth she ate the dirt under the back porch; this story gives us the idea that she spent time playing outside, exploring. We can probably also assume that if she thought dirt tasted like beets, then she may have also thought that beets taste like dirt.

-

-

(2) Give the students eight to ten minutes to write answers to the following question: In the poem "Where I'm From," the poet George Ella Lyon reveals herself and stories about her life to the reader. Support this claim by explaining what you learned about George Ella Lyon through at least three examples from the poem.

-

-

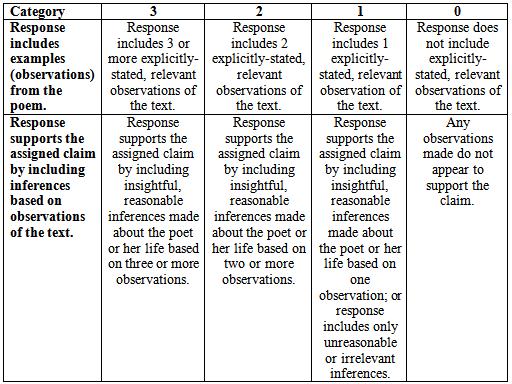

(3) Using a rubric similar to the one shown as Table 2, the teacher would score each response. The rubric includes scoring categories directly relevant to the present unit; additional categories covering organization or usage could be added.

-

-

(4) For the post--test, the teacher could choose whether to have students revise their original responses or write new responses, either requiring them to use different examples or allowing them to re--use the same examples; again, the teacher will be able to use the rubric--based scores to gauge the extent to which the students' observational skills have improved regardless of which post--assessment is used.

Table 2. Sample rubric to be used in scoring the text pre-- and post--assessments.