Language, Art and Writing in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica

Languages evolved as a mean of communication much earlier than the writing. Documented writing as a form of communication emerged when people began putting their thoughts on random objects such as stones, rocks, ceramic and later on, as writing systems developed, papyruses and then paper were introduced. Thus, writing became a sophisticated way of communication and expressing ideas, concepts and phenomena; nevertheless the early writing system were created based on the first pictographs and symbols. The world's writing system began with the early civilizations such as Phoenician, Mesopotamia, Egyptians, Greek and Summarian.

3

In "Languages of Pre-historical Antilles" Cranberry and Vescelieus maintain that "nothing has survived of the lengthy utterances of Taíno Language" (Taínos were one of the tribes in the Great Antilles). Thus, in many of the islands of the Caribbean after the conquest of the Spaniards, languages were wiped out along with the population, and it is therefore very difficult for researchers to study these dead languages. Little is known how developed the languages of great Antilles were when the explorers first arrived in the islands of the Caribbean.

4

When the conquistadors came to the Caribbean Islands, they saw and conquered. The conquerors converted the natives to Roman Catholic and changed the names of the islands to Spanish names. The first contact with the natives was awkward due to the communication barriers. Thus, explorers were not able to make any sense of the utterances of the natives. Nor were the natives able to communicate their way of life beyond what the eye of the explorers could see.

5

For example, Cubanacan (Ciboney name for Cuba) became Juana. Ciboney was one of the tribes of the Great Antilles. The island of Haiti and Dominican Republic became "La Hispaniola".

In the archipelago of the Antilles during the pre-Columbian era, civilizations were developed in the form of small tribes and villages throughout the main islands of what are now Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, and Jamaica. Two main tribes called Ciboney and Taino had already established their way of life and were distinguished from others by their social structure, architecture, pottery and artifacts. However, after the colonies were established, Ciboney and Taino Indians, successors of the Arawak tribes in the Caribbean Islands, were extinguished within a century of the conquest. Lacking the language evidence anthropologist and archeologists have used symbols, art, pottery and paintings to discover more about the way of life in the Ciboney and Taino tribes of the Great Antilles. Ramon Dacal Moure and Manuel Rivero de la Calle in their book

Art and Archeology of Pre-Columbian Cuba

mention that pictographs (rock painting) were very popular in Ciboney culture and they were manifestations of their tradition and artistic creativity. However, Ciboney pictographs were very abstract and quite impossible to interpret because of their indecipherable nature.

6

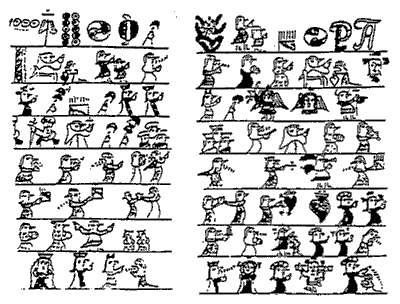

"Taíno pictograph telling a story of missionaries arriving in the island of Hispaniola."

7

Meanwhile, in the Central American peninsula including Mexico, in the late 1400s pre-Columbian cultures were already established civilizations distinguished by their art, architecture, religious beliefs or other forms of worship. Most importantly, pre-Columbian cultures differed in languages. It is believed that thousands of languages in the America were spoken from Alaska to Greenland, including South American indigenous languages before the first contact with the Europe.

8

The European conquest of Latin America was a very long process and included many areas. One of the main players was the clergy. The driving force behind the conquest, among others, was the expansion of Christianity. Moreover, with the fall of the Aztecs, codices and symbols were lost and burned in the center of Tenochtitlan, today's Mexico City.

9

Aztec Gods were slowly replaced by the Lady of Guadalupe, otherwise known as the Virgin Mary. The year 1521 marks the fall of the Aztec Empire. With more than 40,000 Aztec warriors perishing in the battle between Cortes and Montezuma, the new era of Spanish conquest marks the end of the Aztec civilization. Along with the death of the Aztec warriors and their noble leaders, the fall of the empire marks a systematic conversion from the aborigine cultures of Latin America to Roman Catholic beliefs and philosophy. The wars of conquest were not the only decisive factor in the making of history of the entire North and South American continents. Diseases that Europeans brought with them spread rapidly, and epidemics such as small pox played a role in reducing tremendously the Aztec population who vanished under the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

10

The Roman Catholic mentality brought by Spaniards viewed the Aztecs and other cultures of Mesoamerica as having no fixed place in the history. Their existence was not foretold in the Bible; it was not documented anywhere. Cortes considered the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan as the equivalent to the old city of Jerusalem, or the old city of Troy, and he sought to govern it. In T

he

Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire

, John M.D. Pohl and Claire Lyons underline that Spaniards, led by Cortes, saw similarities between the Aztecs and the civilizations outside of "salvation"; therefore, they believed that to govern the New World, it was necessary to apply the laws of antiquity. The old Roman law of

de Jure Belli,

or the right of conquest by war, was very pertinent and consistent with the conquest of the Aztecs.

11

With conquest came not only heartaches but also communication difficulties. The Aztec and the Spaniards spoke two different languages, Nahuatl and Spanish. Cortes relied on interpreters to figure out the Aztecs. One of them, an Indian woman called Doña Marina, who later became Cortés's mistress and bore him a son, is mentioned in many historical documents. Dona Marina, or Malinche, was considered a traitor who betrayed the Aztecs by revealing to Cortes that the empire was falling because of Montezuma's weak leadership.

Daily Life of the Aztecs

by David Carrasco and Scott Sessions reveal that through pictures and painting, important events were documented in the Aztec life. Such events tell the story of Aztec warriors, spiritual beliefs, natural phenomena like the passing of comets, or simple Aztec family life. Later on, even shortly after the fall of the empire, Aztec art, as a form of storytelling, was a sheer representation the Spanish conquest and the heartache that came with it.

12

Aztec art has fascinated many art critics and researchers. The Dominican friar Diego Duran introduced in 1581 the

Duran Codex,

the History of the Indies of New Spain, one of the earliest books of the Aztec history and civilization. The book was initially criticized for serving as a tool to help the "heathens" maintain their culture. The book was a collection of Aztec folktales, stories Duran had previously collected from other friars and the natives. Friar Diego Duran spoke fluent Nahuatl that enabled him to win the trust of the natives and share stories that natives would never share with other Europeans.

13

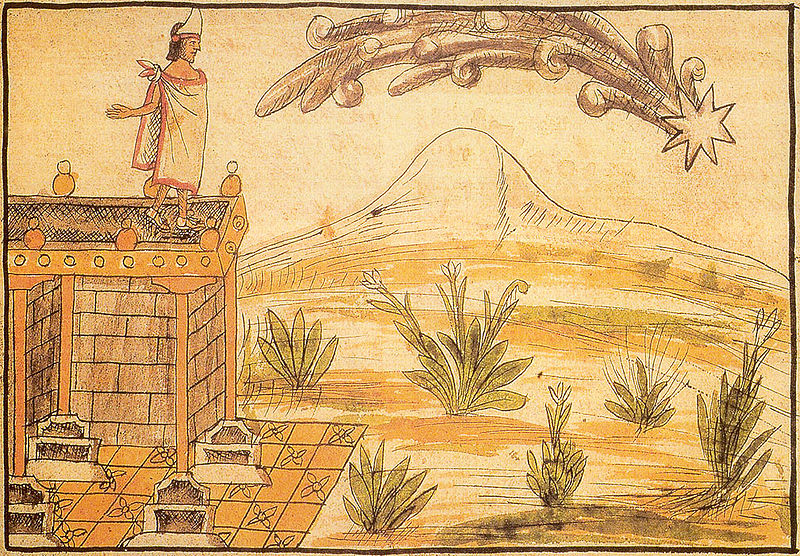

For example, in the picture below, Montezuma has a clairvoyant moment while watching a comet passing by, and it is not the first time we see the use of astrology to interpret different phenomena in the life of the Aztec Empire.

"Montezuma watches a comet passing by."

The image is taken from Codice Duran, Chapter LXIII. According to Duran, the comet was interpreted by tlatoani (the king) as a signal; however, the Mexican doomsayers could not figure out what it was. Montezuma then consulted the Nezahualpilli of Tetzcoco who told him that the comet signals the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan." (Translated from the Spanish version.)

14

Documenting Childhood in Art and Writing: Pre-Colombian Era

In earlier cultures and civilizations, important events were documented through pictography or petroglyphic representations. Visual interpretations of what civilizations considered as important to trace and record were either done through symbols, pictography or petroglyphic images. Interpreting documents was not always easy because of the abstract nature of petroglyphic images. Documenting childhood in pictures or writing depended on how cultures perceived the place of a child in society and the way the civilizations developed. Thus, the Egyptian papyrus drawings reveal an interest in documenting children as part of the society.

15

Documenting events and simple life differs from one civilization to the other. Aztecs pictographs are characterized by symbols that represent a specific meaning, and children are scarce in Aztec pictographs. Generally speaking, Aztec pictographs depict warfare, glory, triumph and defeat. Hence, cultural differences between civilizations clearly represented childhood in various ways, but the idea remains the same, children were a great part of the social structure. The social structure in the Aztec empire, just like those in other earlier societies determined what role children play and how were they brought up. For example, Aztecs, according to pictographs were concerned about their children's education, thus, we can see in them a visual representation of parents bringing their children in school. The pictographs can be interpreted in many ways, but it is evident that Aztec society, as a very structured society, made room for the schooling and education of children.

16

Similarities between the Egyptian papyruses and Aztec pictographs in documenting childhood are remarkable. Since both societies were a hierarchical structure, children's place varied from high social statuses down to slave children being sold in the slave market. In other pictographs, children of the lower class in the social ladder were depicted as slaves for sale, a status that they inherited from their own parents. Overtime children were allowed to buy back their freedom.

17

Documenting Childhood in Art and Writing: Colombian Era

After the Spanish conquest, Native American art changed drastically. It was oriented more toward religious themes and the building of its infrastructure. With the colonizing of the Americas, artists and intellectuals spent their early years in European art schools and universities with the intention of bringing the European culture to the Americas, especially South America. Artists who studied plastic arts came back with European art techniques. Among painters and artists was the well-known painter of the colonial era Cristobal Rojas (who studied Plastic Arts in Paris).

18

During the Columbian era we see a shift from native art to modern art. Murals became a way of expressing what was left of the continent and the indigenous culture. Along with the new techniques artists shifted the themes as well, yet they remained authentic to their roots. Thus we see modern themes treated by Jose Clemente Orosco,

19

and more traditional murals by Diego Riviera.

20

By the 1800s the Latin American Society has drastically changed. Peninsulares (those who were born in Spain) held the highest social rank. The other structures were placed in accordance with race and importance. For example, the blacks and the indigenous were at the bottom of the social ladder, whereas the "Criollos" Creoles (Whites born in the Latin American continent) were a step below the Peninsulares in the social ladder. Regardless of the ranking importance, the social structure and the family as its component were documented in the art work, writings or other forms of documentation.

21

During the colonization of Latin America or the Caribbean, paintings that depicted women of color, servants, and slave masters were very common. Later in the 1800s, artists seemed to diverge from the religious themes and represented more a family theme and the daily life in the new continent. For instance, the Spanish artist Francisco Clapera in his painiting

De Chino e India

depicts a typical family of the Americas. In the center is the head of the household who is the product of an interracial union. He is called "Mulato" (a mix between black and white parents). His wife is an indigenous woman and their child seems to be contributing to the household chores by sorting out what is seem to be cotton for textile. It appears that the family belongs to the artisanal class. But most importantly, we see how the life of children is visually documented during the 1800s.

22

Even though powerful voices rose in the new literary society, Latin American literature was not developed as a literary current until the twentieth century with the introduction of the experimental Latin American novel. Yet one of the most talented philosophical writers in colonial Latin America was Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a self-taught nun who lived in Mexico in the 1600s. Though an autodidact author and a poet, Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz in her work,

Respuesta a la Sor Filotea de la Cruz

(1691), documents pieces of her childhood from a child's perspective. Her exquisite style has become one of Latin American literary jewels. Her writings were artistic, well-crafted written segments of her life. Her work opened new doors for autobiographic writings in Latin America, which was still an underdeveloped or underrepresented genre.

23

The distinction of stories told from a child's perspective and an adult angle is quite evident in the writings. In Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, who offers a series of confessions of her childish manipulations that Sor Juana used to achieve her childhood goals. Her stories are quite entertaining and make the reader think of her as a bright, exceptional child with an embellished thirst for knowledge at an early age. For example, in paragraph seven and eight of the letter Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz writes, "…. I hereby state that before I was three years old my mother sent me and one of my sisters, who was older than I, to one of those schools called Amigas, where we could learn to read. I followed her with affection and mischief. When I saw she was receiving lessons the desire to learn to read caught fire in me so much that I tried to trick the teacher (so I thought) by telling her that my mother had instructed her to give me lessons too."

24

The author brings memories of her own childhood from a child's perspective explaining how she saw the world and how she perceived the learning.

Certainly, there are many ways of documenting a child's life. Besides pictures, videos, journals are compilations of memories that a family holds very dear. However, documenting a child's early years was always done from a parental angle, thus an adult's perspective. Silvia Malloy in her book

At Face Value: Autobiographical Writing in Spanish America

mentions that in Epinal engraving, children were depicted less as themselves, than as miniature grown-ups.

According to Malloy's point, launching childhood memories from the author's perspective created depth, and revealed mysteries of family life

,

which was, interestingly enough, a part of the historical novel, yet not part of the history itself .

25

The concept of family life, as presented here by Malloy, it is in fact the root concept of Latin American social structure. A catholic decree, the "family" in Latin American culture is a social construct held together by traditions and celebrations that mark different stages in one's life. For example, "Quinceñera" a girl's fifteenth birthday marks her entrance to womanhood nowadays documented by videos or pictures, scrapbooks or journals.