Overview and Objectives

From the perspective of a public school classroom it is not difficult to see we live in an unequal society. It is also not difficult to see why: racism, classism, and sexism run rampant, often unchecked. We know through the lens of both news media and modern literature and film (as a glimpse into our modern psyche) that police bias exists, that policy-makers are predominantly white, upper class men who act based on the interest of the white, upper classes. However, these conditions and their implications are dealt with in English class, history, even social science classes and units. It is important to understand that a key factor driving classes apart in America is unequal distribution of income. In order to do that, we’ll need to understand: that it exists, how it exists, where, why, and what to do about it. Anthony B. Atkinson, as well as several other economists and scholars, maintain that inequality is not only a matter of policy or public perception, but a systemic flaw of our take on capitalism and influence on world policy. And, while it has that big a scope, we will focus on the smaller aspect of our society that may ripple into all others, and therefore deserves our scrutiny and, indeed, change: our national system of education.

There is indeed a certain amount of argument one can make for changes to the educational landscape based on observation and intuition. It is not hard to imagine that access to more books or other such resources will impact a child’s development and lead to a higher likelihood of success. However, there is also actual research to

prove

that certain educational considerations impact a person and can dictate whether they are on equal footing by the time they graduate from college. Raj Chetty along with other economic researchers analyzed the economic impact of project STAR, an economic experiment in the 80’s involving over 11,000 students, ultimately concluding that class size, peers, and teacher experience in lower grades have a lot to do with how successful a person becomes (more on this study in the below sections).

That being said, students in an urban district are more likely to be disadvantaged than in suburban school districts. That is, the instance of underprivileged students is more common. Therefore, I believe it is of significant importance that economics be taught in an urban school – especially the economics of inequality, and especially in a school where there is not a class available solely devoted to economics. This curricular unit is designed for a class on African-American history and literature, and therefore the introduction to inequality aspect will tie in with the history of a marginalized community. However, the principles of economics explored within this curricular unit will be relevant to teach any student, in any applicable class where sociology, history, business, or economics are taught, and could be applied to larger focuses on any number of topics. It is important for students to be able to explore, analyze and interpret data. It is important to students of all socioeconomic backgrounds to understand how to do that, and how to put it in context.

It may be overly ambitious to expect teenagers to develop a worldly enough scope to start seriously considering the inequality in this country, but I don’t necessarily believe it is. In a world where they have constant access to what’s going on around them – unrest, brutality, unequal treatment; even to less controversial evidence like celebrity lifestyles or even that of their friends in the same school – I don’t think it unreasonable to expect that a high school student would have the wherewithal to at least take seriously the study of the principles and ideas found herein. I've learned through my study of economics that you don’t have to be an expert or analyst to understand important concepts regarding our economy, the reasons for inequality, or what we can do to help sway it; or, perhaps most importantly, why it’s so important to change our country's direction to a more evenly distributed structure of wealth, income, and opportunity. Therefore, we will focus in this unit on the general concepts of economic inequality, as well as where opportunity is denied or different for varying aspects of our society.

In order for students to effectively learn about inequality in this regard, it is important to begin with an overall view of economic inequality, for which we turn primarily to principals explored in this Yale seminar, as well as the work of Anthony B. Atkinson, an acclaimed British economist widely regarded as a pioneer in the study of inequality.

5

In his book

Inequality: What Can Be Done?

, he explores many different aspects of inequality, along with how and why our changing world has yielded so much of it. In order to fully understand these concepts, we will begin with an overview of economic inequality and how to interpret data relating to it, as well as its implications for equality of both opportunity and outcome. We will then delve into how it impacts educational opportunity, and how that has become cyclical. Indeed, the very concept of inequality of outcome does not get enough attention, as it cycles very fundamentally into the concept of inequality of opportunity, which gets most of the attention.

Primer of Economic Inequality with Regard to Opportunity and Outcome

Introduction to Income Inequality and Analyzing Data

In his book, Atkinson deals with not only

where

inequality exists, but also how it came to be, what the persistent societal actions and policies are that fuel it, and what can ultimately be done about it. There are obvious answers or culprits: technology, evolving tax structures, and others, and we begin there. It’s hard to tell at the surface level which aspects of society in the last 60 or so years have been the dog wagging the tail or vice-versa. Technology has propelled mankind into a new era of potential. We have seen advances in the last 60 years that amaze and astound to this day, and can improve both the quality and length of our lives. However, with technological advancement comes human nature – that of those with power and influence utilizing it to improve their own lives and that of their ilk only. “Technological progress is not a force of nature but reflects social and economic decisions.”

6

We are not simply adrift on a wave moving us forward, our societies have made very conscious decisions with regard to technology, progress, and the economic implications of those things. “Choices by firms, by individuals, and by governments can influence the direction of technology and hence the distribution of income.”

7

It is not surprising, then, based on both human nature and those for which the power of controlling progress rests, that in the last few decades – which have seen unprecedented human progress in technology – we have also “evolved” into a quite unequal society. The rich get richer, as they say, and that’s all there is to it.

Or is it? Atkinson explores the data in his opening chapter, as will we in this curricular unit, with the qualifier, as he states it, that “every equation halves the number of readers,” immortalized by Stephen Hawking.

8

This adage will be good to remember, in a predominantly theoretical class, when we spend time on both the importance and understanding of how and why to interpret hard data when exploring economics and, really, anything. And even though Dr. Hawking was referring to equations, it may be helpful to frame interpretation of all data – for our purposes mostly graphs, as something that is valuable even if their instinct is to shy away from it. The advantages of technology have spurned more disadvantages than simply inequality of income and wealth. The disadvantage, especially to young people, of a 24-hour news cycle, unending news and information “sources,” and myriad daily clickbait deferring them from truth, makes it all the more important they be ready, willing and able to navigate real data, and know where and how to find it. The disadvantage of machines doing the jobs of people, outsourcing, and other labor and economic implications of technology make it all the more important students are aware of what they must prepare for, and that inequality cycles with the very condition of economic changes due to technology growth.

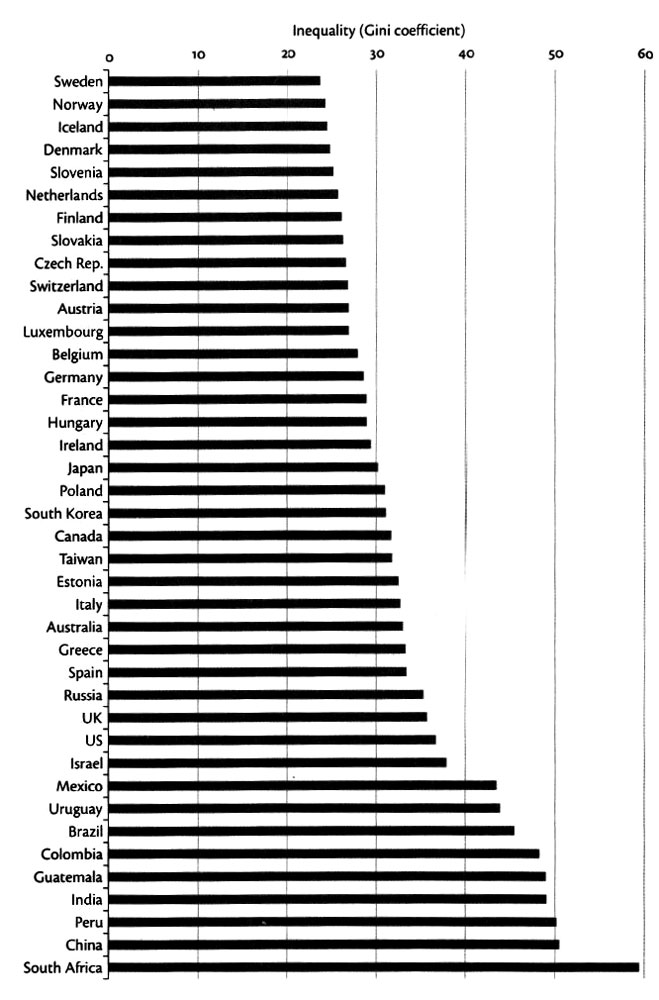

To that end, we will begin by introducing a chart showing where the U.S. lies in global economic inequality – near the top. The following graphic utilizes the Gini coefficient (explored later in this section) in order to show economic inequality across 40 developed countries. In it we see the U.S. is far more unequal than most European countries including the U.K., which we just edge out. This is a good graphic to start with as it does not take much scrutiny or practice to interpret, as it is a simple bar graph, which makes it a good introduction to interpreting graphic data. The way it was calculated, however, is a more complex aspect of economic measurement that will be an important lesson to students with regard to just how inequality is measured: the Gini coefficient.

The extent of world inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, from

Inequality: What Can Be Done?

by Anthony Atkinson. In a simple bar graph, we can see the U.S. as a nation with a high amount of inequality.

9

To measure inequality, Atkinson utilizes the Gini coefficient: an economic measure for inequality calculated between 0.0 and 1.0, or, as Atkinson uses it, between 0 and 100. 0 would be a completely egalitarian society – one in which all income is equally distributed. 1.0, or 100, would be a society where only one person controls all the income. In reality, as can be interpreted from our first chart of 40 developed nations ranked by level of inequality, the Gini coefficient falls between roughly 24 in Sweden (where there is less inequality) and nearly 60 in South Africa where inequality is considerable.

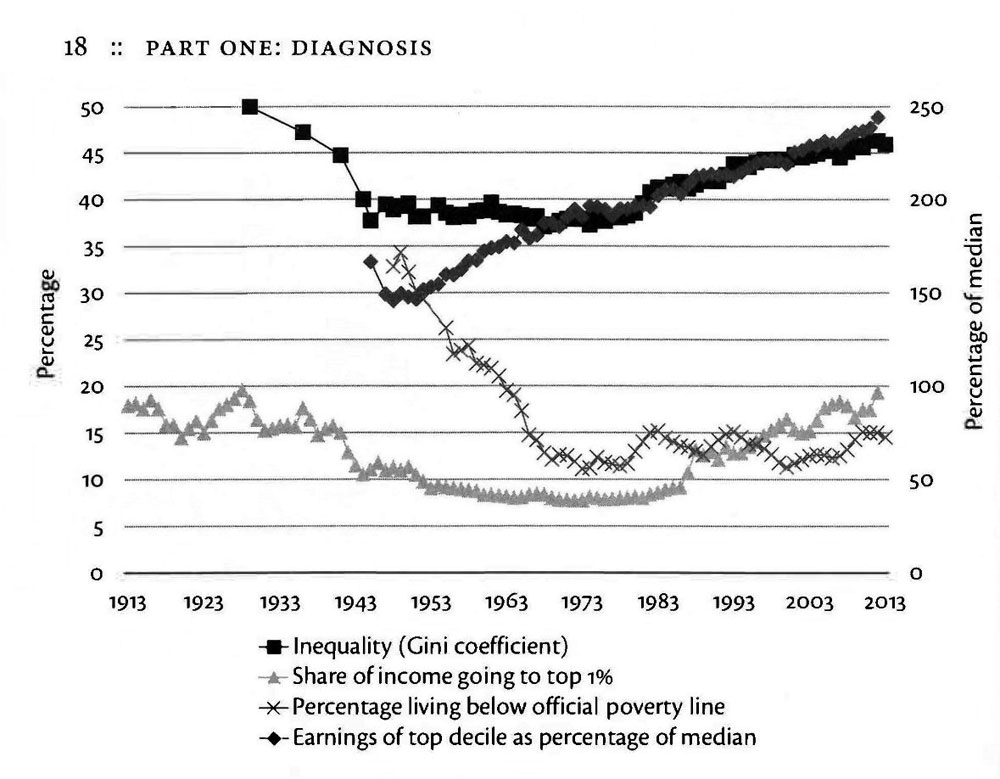

The next step is to look at the breakdown of income inequality using the Gini coefficient in the U.S. For this, we will explore another graphic.

Using the Gini coefficient to measure U.S. inequality. Here, Atkinson breaks down how inequality here has changed over the years, and we can see that it has steadily risen up to roughly the present.

10

As the data indicates, inequality of income distribution in the U.S. dipped to lower levels after World War II, and has slowly crept back up over the last 70 or so years to peak where it was pre-war – a high level of inequality. And we see it every day. Our students are at least peripherally aware of the crash of 2008 and its continuing after-effects on the working class. They see CEO’s on yachts every time they flip through television channels, either in the news or on scripted shows. They may or may not know that CEO’s make, but whether or not they’re quite that aware of the details, the level of inequality is apparent enough in our everyday lives that the average public school student would not be

surprised

to learn that there are measurable factors telling us so.

The Outcome Imperative

There are two central concepts of inequality to take a look at with students after establishing the aforementioned data: that of opportunity, and that of outcome. Equality of opportunity is tough to argue with, and most do not. It would be hard for a politician, policy maker, teacher, parent, or even friend to argue against everyone starting on a level playing field. This opportunity certainly does not exist uniformly in a capitalist society like America, but we can strive for it, and do. Public school itself is a quintessential if flawed example of a society banding together to try and promote its members to all start with equality of opportunity. Does everyone in American have the right to a free and appropriate public education? Theoretically, even legally, the answer to that question should be yes. Does everyone have the opportunity for the same

quality

of education? Of course the reality of that is, no. People born to wealthy families in wealthy areas have better opportunity for a quality public education simply by virtue of where they live.

It is possible that an overhaul of funding formulas which would redistribute resources among school districts would be significantly helpful in this, but I see this as unlikely, especially in the short run. And so it is that the importance of equality of

outcome

is so important.

It wouldn’t matter if everyone started from the same starting line in a race. If some in that race were in peak physical condition and others were crippled, due in no part to anything but how and where they were born, the race could never be considered a fair one. We must focus on outcome in order to ensure proper equality of opportunity. Everyone in the race must have equal opportunity to use their natural abilities and effort to win, not just start. Therein we consider the prize structure. “It is the existence of a highly unequal distribution of prizes that leads us to attach so much weight to ensuring that the race is a fair one. And the prize structure is largely socially constructed.”

11

For example, patenting. People who acquire patents in America are far more likely to be from high income families than not. According to Brookings (working with data from the Equality of Opportunity Project), inventors are twice as likely to receive patents by the age of 30 if they are in a family in the top 20% of earners.

12

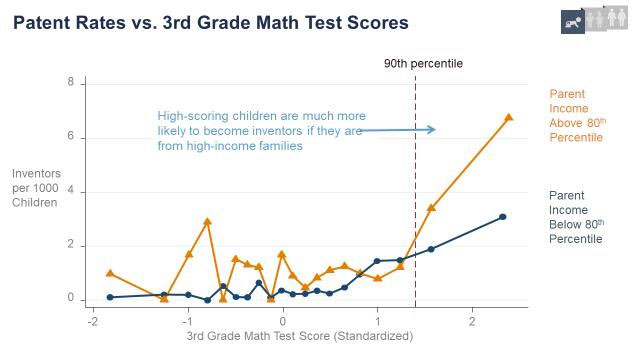

Furthermore, the following chart shows a similar statistic but takes into account math scores. Even if the inventors from lower income families test well in math (an early indicator of innovative aptitude), they are less likely to attain a patent than those who score similarly but simply are born into different families.

13

It is by not virtue of their talent, intelligence or effort.

Inventers are at least twice as likely to attain a patent if their parents’ income is above the 80

th

percentile than below it, according to this data from the Yale Seminar:

Introduction to Income Inequality

.

14

According to the Brookings article: “There are obviously many factors at work here, including simply being aware of the process of applying for a patent. But if inventors are drawn largely from richer families, to the extent that their inventions are successful, intergenerational mobility will worsen rather than improve.”

15

Here, it seems they use the fact that lower income inventors simply don’t know about the process of applying for a patent as a qualifier, but I think it’s the whole point. People from lower income families are not taught that they need to be aware of these things. It could be argued that ignorance is no excuse, but the higher earning families

do

teach their children these things, or are perhaps connected to people who can move their kids along in the patent process. Either way, this creates inequality of outcome.

Why is this? Again we see that it is not the natural evolution of a capitalist, technologically advanced society that creates inequality, but the decisions of that society, or the powers that be in that society. Organizing said prize structure so that the top decile of income earners essentially awards themselves in perpetuity creates our unequal society. While we all claim to care about equality of opportunity, we need to realize that without attention to equality of outcome, equality of opportunity cannot actually exist – one begets the other. There is not opportunity for the next generation if their parents do not have access to that opportunity. If progeny of educated parents statistically are more likely to attend college, for example, then an individual does not have equal footing with other college applicants unless their parents have gone to college. The cycle towards equality needs to start somewhere, when “even with need-blind admissions, kids from wealthy backgrounds have huge advantages; they apply [to college] having received better schooling, tutoring if they needed it, enrichment through travel, and good nutrition and healthcare throughout their youth.”

16

Conversely, students from needy families have not only not had these advantages, they are more likely to suffer from trauma, poverty, classism and other factors. Really, it’s a two-way swing in the wrong direction for them simply

not

being born elsewhere.

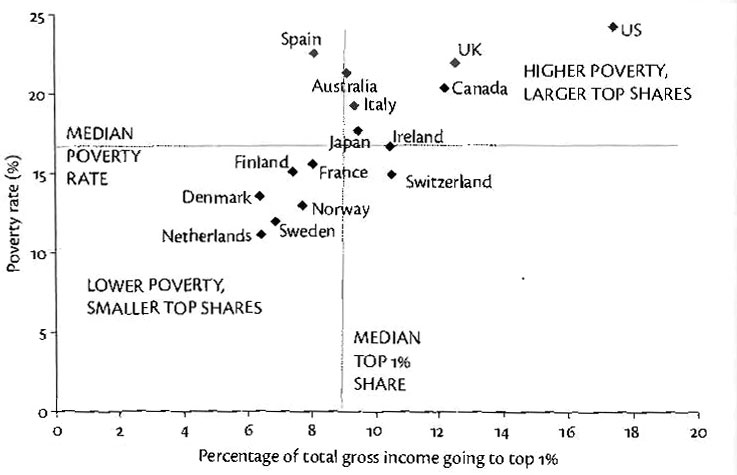

Poverty is of course a significant concern. However, poverty has been “fought” in modern times since 1965 and, while improved, is still a pervading issue, so we need to focus on the fact that top earners have not been scrutinized until modern economics research, such as we are exploring here. Income distribution inequality favors people not based on their personal merit, but “opens doors, especially for people who may not boast the strongest talents or work ethic.”

17

Atkinson shows that the U.S has among the world’s top poverty rates as coincides with earnings of our top 1%.

18

And finally we will take a look at the importance of education to right the imbalance of income distribution, particularly where education could be the biggest factor if we are to consider opportunity of outcome.

Opportunity and Outcomes in Education

Even if every child in America had, at the outset of their high school education, equal opportunity to achieve – i.e., grades, test scores, and like indicators for successful college acceptance, without considering equality of outcome, the level playing field can be lost the moment they step onto the college campus. Firstly, many college campuses are designed for the comfort and inclusion of those from more financially secure households, and student body makeup that of a more socioeconomically supported student, which could and does make students from lower income families often feel out of place, while those who come from wealthy families have better opportunity to do well. “Poor kids who do make it to college will have to spend more time scrubbing toilets and dinner trays and less time studying.”

19

Equality of opportunity is a wonderful thing, but if we consider again that it cannot truly exist without equality of outcome, then getting to college is not enough. We must work toward a system in which any young person has the same opportunity to be successful in college as anyone else.

But once on the college campus, there is also the opportunity to thrive. There is something special about this archetypal formative period, so special that it accounts for much of our socioeconomic mobility, and especially accounts for top earning families to continue on as such. According to the Equality of Opportunity Project, college campuses widely exhibit socioeconomic makeup similar to that of the average city with regard to a telling indicator: income segregation. Furthermore, “children with parents in the top 1% are 77 times more likely to attend an Ivy-Plus college than children with parents in the bottom 20%.”

20

77 times more likely

. This statistic speaks heavily to the importance of college for top earners, ipso facto its significance as a marker for equality of opportunity (and therefore outcome). It is worth, in fact, noting the findings of the Equality of Opportunity Project regarding outcome specifically:

At any given college, students from low- and high- income families have very similar earnings outcomes. For example, about 60% of the students at Columbia reach the top fifth from both low and high income families. In this sense, colleges successfully “level the playing field” across enrolled students with different socioeconomic backgrounds. This finding suggests that students from low-income families who are admitted to selective colleges are not over-placed, since they do nearly as well as students from more affluent families. This result also suggests that colleges do not bear large costs in terms of student outcomes for any affirmative action that they grant students from low-income families in the admissions process.

21

Let’s unpack this. Low income and high income students show similar results, proving they deserve to be there, and once given that opportunity, make the best of it. There is mobility at top colleges like Columbia, and admitting low income students does not “cost” the college. Now, Columbia admits an impressive makeup for a top “Ivy-Plus” college, as its student body is comprised of 13.4% children of top 1% earners, while boasting 21.1% from bottom 20% earners. However, this is rare in top colleges; many are weighted in the opposite direction. For example, one of the most unbalanced, The University of Washington in St. Louis, is comprised of 21.7% children of top 1% earners, yet only 6.1% from bottom 20% earners.

22

But the biggest takeaway from the Equality of Opportunity Project’s findings is that college levels the playing field. Grooming our country’s students to be successful there is imperative to equality.

So how best do we strive toward this equality of outcome in the form of college readiness, opportunity for acceptance, and ultimately success there? Studies show that early education is a likely indicator and a powerful foundation for that outcome. Project STAR, an educational opportunity experiment conducted in the latter half of the 1980’s, produced many fascinating conclusions. Low class sizes are very expensive, and are far more common in school districts with more money and resources, and a lower population. It is often argued by policy-makers in larger, inner-city districts with lower funding and massive amounts of students to service that larger class sizes are inevitable. And the way the system currently exists they may be correct. However, they must face facts that is does affect how much a student learns. Chetty et al. explain in an economic analysis of the report that “The experiment was implemented across 79 schools in Tennessee from 1985 to 1989. Numerous studies have used the STAR experiment to show that class size, teacher quality, and peers have significant causal impacts on test scores.”

23

From this analysis it is clear that there is an impact. And yet it still leaves open the important question as to “whether these gains in achievement on standardized tests translate into improvements in adult outcomes such as earnings.”

24

The previous study on the role of colleges in mobility indicates that college is the place that does.

There is not a lot we can tell about what an adult will do with a strong, solid educational background, at least for these purposes. And so it is that we hunt for what will cause that playing field to actually be level: equality of opportunity through college. Joseph Fishkin of University of Texas asserts that “parents with more education more often manage to move their children to. . .advanced, academic tracks,” which is due to the fact that their “children grow up in an environment of ‘concerned cultivation,’ in which parents inculcate middle-class norms, a middle-class sense of entitlement, and the academic skills of a future college student.”

25

If we were concerned about the cultivation of all our nation’s students, we’d need to focus on equality of their educational outcome. The fact that educated parents more often have educated children proves that outcome leads to opportunity for the next generation.

Conclusion: Shifting Paradigms

According to Deborah Verstegen of the University of Nevada Reno, we have been experiencing a “watershed era in education as [we] move from. . .minimums and basic skills to the new equity. . .of excellence in education and proficiency outcomes for all children.”

26

I very much hope this is true, but I see what it looks like in the classroom every day. When so much is demanded of our students, their teachers, and the districts that sponsor them, our current era of education essentially demands that students produce passable outcomes, defined, more often than not, as college admission. Family income and education, and even home life, are not considered as frequently as quality of school district or instruction, and much of the onus is placed on schools to produce these outcomes without attention paid to what uncontrolled aspects of a student’s life come into play: family stability, income, mental health, access. There are economists, such as John Roemer of Yale University, who tackle certain economic theories based solely on aspects of an individual that is

out

of their control

27

– the very things that judges of educational opportunity often ignore. It is the aspects that are

out

of a student’s control that need to be focused on in order to minimize inequality of outcome.

All in all, I believe that there is a mindset at work that needs tweaking. If we as a society, starting with individuals – both “have’s” and “have-not’s” – can begin to think along the same lines, improvement would be inevitable. And by along the same lines I quite simply mean, after studying a very complex concept, that each human should have opportunity to reach their potential. Currently, we feed dynasties, compounding rampant inequality, scales tipped ever more heavily in the direction of the rich, leaving not only the other side of the scale empty (the very poor), but everything in the middle struggling to keep up. There is no societal need for this, nor economic. If we can give our students the fundamental knowledge to simply keep this

in mind

as they become the next generation of decision makers, it will at least have been better than my generation. And if there is no way to tip the scales immediately, I hope doing a little better each time will form history in a way that posterity will someday achieve the human concept so sought after, but unfortunately not achieved by all: equality.