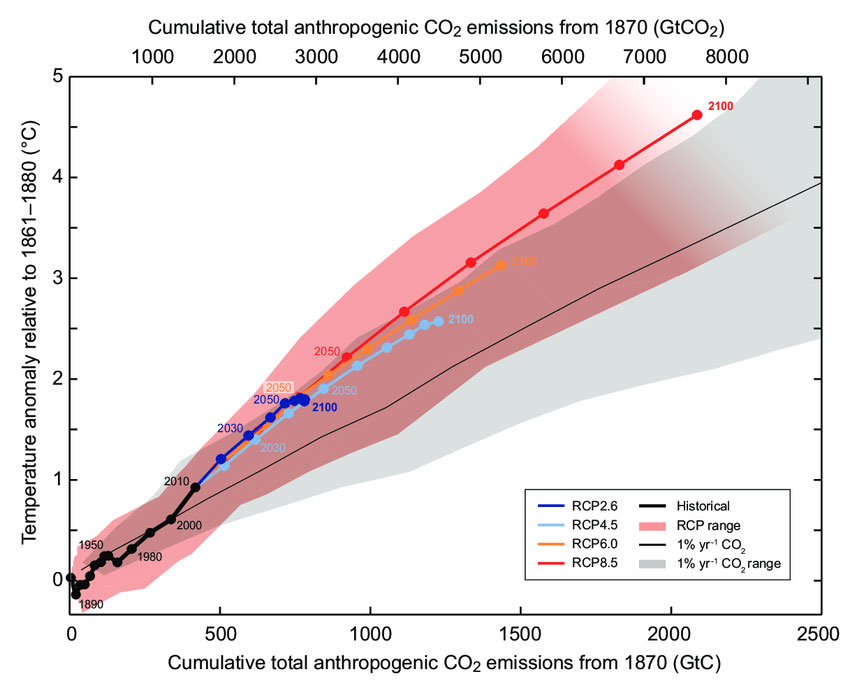

Greenhouse gases will continue to be released into the atmosphere. Present day society’s runs on the energy collected from the burning of fossil fuels. With the continued use of fossil fuels, there will continue to be an increase of warming in our climate. Using different models that can consider different representative concentration pathways, scientists are able to make estimates of climate impact in the year 2100. These models can forecast what would happen if very strict limits are placed into effect and they can make a prediction on what would happen if no mitigation strategies are started. This way, they can look into both best case and worst case scenarios, within reason.

Mitigation is a human intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases. Between the years of 1970 and 2000, there was an increase of 0.4 gigatons of carbon dioxide (GtCO

2

) per year.

13

As time progressed, the amount of carbon dioxide released each year increased to 1.0 GtCO

2

per year. Over half of the combined carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere in the past two hundred and fifty years have been within the last forty years. In 1750, the combined carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and cement production was approximately 420 GtCO

2

. In 2010, that number almost tripled and released about 1300 GtCO

2

. Without any addition mitigation, the results could be an average surface temperature increase anywhere between 3.7°C to 4.8°C by the year 2100. In addition to an increase of surface temperature, an increase of extreme precipitation in areas of high latitude and along the equator will be observed. Extreme precipitation would include more intense and more frequent rainfall. In areas along the tropics, this could be seen as an increase in frequency of monsoons.

If left unchecked, as the temperature increases, ice melt within glaciers and permafrost will increase. By 2100, glaciers will start to melt at a faster rate and decrease anywhere between 35 to 85%. Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover will decrease and 25% and 81% of permafrost will have melted. With the combined increase surface temperature and ice melt, the sea level will also start to rise at a more aggressive rate. If no mitigation strategies have been put in place, sea level could rise by 0.82 m by 2100. Thermal expansion would account for 55% of the rise and glacial melt would account for 35%.

Figure 4: Global mean surface temperature increase as a function of cumulative total global CO2 emissions from various lines of evidence. Multi-model results from a hierarchy of climate-carbon cycle models for each RCP until 2100 are shown with coloured lines and decadal means (dots). Some decadal means are labeled for clarity (e.g., 2050 indicating the decade 2040−2049). Model results over the historical period (1860 to 2010) are indicated in black. The coloured plume illustrates the multi-model spread over the four RCP scenarios and fades with the decreasing number of available models in RCP8.5. The multi-model mean and range simulated by CMIP5 models, forced by a CO2 increase of 1% per year (1% yr–1 CO2 simulations), is given by the thin black line and grey area. For a specific amount of cumulative CO2 emissions, the 1% per year CO2 simulations exhibit lower warming than those driven by RCPs, which include additional non-CO2 forcings. Temperature values are given relative to the 1861−1880 base period, emissions relative to 1870. Decadal averages are connected by straight lines. For further technical details see the Technical Summary Supplementary Material. {Figure 12.45; TS TFE.8, Figure 1}

Each area around the world has a vastly different climate and therefore, would be affected differently by the effects of climate change brought on by greenhouse gas emissions. If mitigation strategies do not fix the problem or do not fix them fast enough so that adverse effects are not stopped in time, adaptation strategies must be put into effect to live with the outcomes. Certain climate related drivers of impact have been identified, along with potential adaptations to help get us through.

The idea of changing to adapt with the climate may seem simple at first, but will weigh heavily on the economy. Small islands in the Pacific will have an issue to adapt due to their high coastal area to land mass ratio. It would be far too financially taxing on an area like that to start coastal renovations like sea walls. Areas in Africa that are expected to see a change in their precipitation can also bring new vector-bourne diseases. A simple solution would to increase health care in those areas, but those areas may not even have a basic healthcare system established yet. These solutions may seem easy enough, but without proper funding, cannot happen. To combat sea level rise, costs associated with damages and adaptations would cost several percentage points of gross domestic product.

16

To best live with climate change, would be to slow down the carbon emission and adopt mitigation strategies to reduce carbon levels to pre-industrial times. In the meantime, an adaption that could help many people would be to install early warning systems to alert citizens of potential hazards.