In this section, students will focus on the essential questions: 1) Why do humans need story? 2) How are stories built? Students will use texts and videos to explore the act of storytelling as part of what makes us human, having foundations in our social interactions and even in human biology. Students will first explore historical milestones in storytelling and will then look at what neuroscientists say about how stories engage our brains. This section will take about one week, using 90-minute class blocks.

Scholars cannot pinpoint an exact year when storytelling emerged, but they believe it to be soon after humans developed capacity for language. The Lascaux and Chauvet caves in southwestern France are famous for early evidence of storytelling, which takes the form of horses, bison, lions, mammoths, and deer that were painted on the cave walls around 30,000 years ago. In recent years, a series of warty pigs painted on cave walls in Indonesia have been dated to at least 45,000 years ago. Based on the positions and sequencing of the images in Lascaux and Chauvet, archaeologists believe these animals would have given the illusion of being in motion when viewed in the flickering of firelight—a prehistoric form of animation. Scholars view these paintings as visual stories, which likely were viewed by their communities alongside oral storytelling traditions.

More recent history demonstrates the presence of extensive oral storytelling in pre-literate societies. The earliest known written stories are widely acknowledged to have first been passed down by spoken word for generations. This applies to the earliest known epics, including: Gilgamesh, chiseled into clay tablets in Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE; Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, scribed onto papyrus scrolls in Greece around 700 BCE; and the Mayan Popol Vuh, which was first written down in the Mayan language of K’iche in the 1500s and was later written in Spanish in the 1800s. This heritage of oral storytelling applies to most traditional myths, fables, fairy tales, folk tales, and creation stories. The longevity of oral storytelling has been documented through stories from societies that did not use writing until the 1800s. The Klamath people of Oregon, for example, tell a story relating to the formation of Crater Lake, which geologists can date to a volcanic explosion that occurred around 7,600 years ago. Students can relate to oral storytelling within their own lives today, whether it be a family story told by a beloved grandparent, or the tale a middle-school mishap that travels by word-of-mouth at lightning speed.

While the process of storytelling is enduring, it has been changed throughout time by various human inventions. Writing itself was independently invented multiple times, including in cuneiform in Sumer (modern-day Iraq) by 3100 BCE; in characters carved into oracle bones in China by around 2000 BCE, and in symbols found in Mesoamerica by around 1000 BCE. Written word was the first in a series of inventions that changed how stories traveled across time and space. This phenomenon continued with the invention of Gutenberg’s moveable-type printing press in 1440, the rise of radio and film in the early 1900s, and the more recent internet and social media revolution. Today stories are even being told through such formats as video games! Each of these developments has expanded the audience for stories and the formats in which they are told.

It is valuable for students to recognize that writing, movies, and digital storytelling are not givens, but rather are the result of human ingenuity being applied to the question: How can we communicate effectively to different audiences and for different purposes? Even as technology changes and new storytelling formats have been added, the need to be able to process and generate text has not become obsolete. A meme, for example, may entertain audiences and promote social commentary. But it will not provide doctors with the depth of information needed to treat patients. Exploring these differences can reinforce the relevance for students of becoming strong readers and writers of stories themselves.

In recent years, neuroscience research has documented that human brains have a biological response, as well as a social response, to narrative stories. Scientists have recorded that reading, listening to, and viewing stories activate multiple sections of the brain, stimulating the brain to make connections between sensory input, emotions, and information. Researchers have linked these brain responses to higher social awareness, memory, and learning. A well-known psychology experiment from the 1940s, called the Heider-Simmel illusion, demonstrated that the desire for story is so hard-wired into our brains that people will project a sense of narrative even when one is not necessarily present. In this experiment, scientists showed viewers a 1-minute stop-motion video in which geometric shapes move around. When asked to describe what they had just seen, participants did not say they had watched several triangles and circles moving around. Instead, they described seeing a scene unfold, as if the geometric shapes represented characters in a story.

Students are particularly interested in content that helps them understand themselves. Thus, exploring how their brains work increases the relevance of our exploration of narrative. The activities in this unit are an opportunity for students to look at the essential questions about story from historical, scientific, and literary perspectives. It’s hoped that this framing would encourage students to be more curious and more reflective about their own reaction to various stories. As the school year continues, teachers can refer back to these concepts to support making meaning from stories and to also use narrative to promote social awareness and a healthy learning community.

Activity 1: Sparking Curiosity

This lesson will be used to frame the unit. Students will start with an anticipation guide as a bellringer. They will circle a response for the following prompts: 1) Words are required to tell story. True or False. 2) Without ever being written down, spoken stories have been passed from one generation to the next for how long? a. 500 years b. 3,000 years c. 7,000 years. 3) The fairy tale commonly known as Cinderella has more than 500 different versions. True or False. Students will also write one or two complete sentences in response to each of these questions: 1) What is a story? 2) Who tells stories and why? 3) Why do people respond to stories? Students will save this anticipation guide in their notebooks to refer to later as we go through the unit.

After this opening, I will introduce the students to the essential questions of our Storytelling unit. As a whole group, we will read a brief article about the history of storytelling that references prehistoric cave painting, oral storytelling, and early epics. With this article, I will model annotating and using the Beers and Probst stance of asking “What surprises me?” as a lens to read nonfiction. At the end of the article, we will together generate a list of facts in the following categories: 1) Wow! Fact, 2) Useful Fact, 3) Most Important Fact, 4) Important Dates. As part of this conversation, I will model—and invite students to practice—the process of putting facts from an article into their own words.

Activity 2: Storytelling Across Time

This lesson will be spread across multiple class periods. It will start with a bellringer asking students to freewrite based on the following prompt: Remember a story (not a video) that was told or read to you when you were a young child and which you loved hearing again and again. What was the story? Who told or read it to you? Why did you love this story so much? Students will be invited to share their responses with a peer and then the whole class. A bellringer for another day would be to ask students to brainstorm with a partner and write down as many story genres as they can think of (i.e. mystery, science fiction, etc.), and to circle several that they enjoy.

The main activity of this lesson is for the class to work together to create a shared reference resource. Together, we will create a “Timeline of Milestones in Storytelling.” Students will have a choice of topics relating to storytelling throughout history, and each student will then annotate an article and make a slide with their own fact list. The activity on this day repeats the steps of the previous day, but with students working independently. Topics will include: prehistoric cave art, oral storytelling, invention of writing, earliest written stories, myths and fables, the Cinderella fairy tale, invention of the Gutenberg press, invention of the novel, invention of radio and film. The articles will offer different reading levels, and video options will be available for learners as needed. The databases that are available to teachers through digital library sites such as Britannica School and Gale in Context are good sources for articles on the specific topics. In addition to the key facts, students should add a relevant image to their slide. After students complete their slides, they will share them with a peer.

Next, students will present their work to the class. As we move through the presentations, we will pause as needed for students to record key ideas in their notebooks. One notebook page will be divided into three columns, labeled “Vocabulary,” “Definition,” and “Examples.” We will cover the following academic vocabulary: oral storytelling, epic, folk tale, fable, myth, fairy tale, novel. Students will leave room in their notebooks to continue adding to this list of academic vocabulary about story formats throughout the year. After students present the relevant slide, I will project a definition for students to write down, and draw connections between it and the student-generated content. On another page in their notebook, students will take notes on inventions. On this page, the three columns will be labeled “Invention,” “Dates used,” and “Impact on Storytelling.” Topics covered on this page will be painting/drawing, writing, printing press, radio, movies, internet, and social media. Although information for most of these inventions will come from the student presentations, I will provide the information for the last two items. During or after the presentations, students will write down three facts that surprised them from any slide that was not their own. Later, the completed slide deck will be posted in the digital classroom space to be an ongoing resource for students; slides may also be printed to display to make a visual timeline in the classroom.

After the presentations, students will debrief in small groups. They will discuss what surprised them about storytelling, and why that information was a surprise. Students will brainstorm together to list in their notebooks as many places as they can think of where they hear and see stories today. Students will report out from their small groups to generate a class list on this topic. Students will continue working together to fill in a Venn diagram comparing similarities and differences among storytelling today and storytelling in the past. Students will then report out.

Activity 3: Components of Narrative

As a bellringer, students will respond to the following prompt in their notebook: Review the list of stories we have discussed, and your brainstorming about modern stories. Reflecting on all the types of stories that people have told, why do you think people tell stories? Students will share their response with a peer, and then share out for a whole group discussion. Key ideas that relate to the previous readings and discussions would be: to share information, to connect with other people, to be creative, to cultivate empathy, to persuade people, to teach values, to build a shared sense of culture, to explain things, and to explore “what if?”

Students then will compare three types of stories—told in different formats, from different eras and cultures—to identify the main components of narrative. Students will be given two questions to guide thinking as we review these stories: 1) What is the purpose of this story? 2) What are the building blocks of a narrative story? In their notebooks, on the academic vocabulary list begun above, students will add a definition for “narrative.” Because these are middle schoolers, they may bring prior knowledge to this discussion. Before reviewing the stories, I’ll invite them to name any components they already know that a story has to have. Character and plot/conflict are the most likely answers for students to have at the ready. This would reinforce that the most essential elements of a story are that it is about someone/something and that something happens. We will then review the definition of fable from our notebooks, and students will read to themselves a short fable, attributed to Aesop in Greece, around 600 BCE. We will review the definition of an epic story, and will then watch a short video describing the Popol Vuh, a Mayan creation story that was passed down for centuries before being eventually written down in a Mayan language in the 1500s, and then translated by Spanish colonizers in the 1800s. We will also view a short, animated video. After the reading and viewing, students will work in small groups to complete a graphic organizer to describe the audience and purpose of these stories and to identify the characters, plot/conflict, setting, and theme of each story.

Drawing on the information from the graphic organizer, we will as a class write a RACES-model paragraph to answer one of the questions that students encountered at the start of the unit: What is a story? The RACES acronym stands for: Restate the question, Answer the question, Cite Evidence or Examples, and Sum it up. I will model writing the paragraph for the whole group and invite student contributions. Students can copy down our group paragraph, or write their own, into their notebook and must label the different parts of the paragraph.

Activity 4: Narrative and Neuroscience

As a bellringer, students will respond to the following prompt in their notebook: We have been talking about how stories relate to human culture because we use stories to build communities of shared ideas, perspectives, and values. Do human bodies need stories to be healthy, just like we need oxygen to breathe and food for energy? Explain your answer.

The main activity will start by watching a video of the Heider-Simmel illusion. After the video, students will be asked to write down a short description of what they saw. Students will be invited to share. I’ll explain that although the video is a stop motion video of several geometric shapes moving around, when most people view the video, they ascribe a narrative story to be happening. Why? Because human brains are wired to look for and interpret stories. I will show students diagrams illustrating how reading and engaging with stories stimulates different parts of the brain, helping us to process information and build personal and social connections. I will also review key vocabulary that will help students be successful with the article we will read. We will review procedures for annotating nonfiction text, particularly reading with the guiding question of “What surprised you?” In addition, I will invite students to add another stance, with the question of, “What changed, challenged, or confirmed what you already knew?” Students will read an article and complete a graphic organizer to demonstrate their understanding. In addition to identifying the four facts as done in the previous articles, students will respond to prompts about what changed, challenged, or confirmed what they already knew. After completing their graphic organizers, students can share their responses with peers.

Activity 5: Summing it Up

In this lesson, students will circle back to the anticipation guide from the first day. Based on what they have learned, would they answer the short questions any differently? Students previously wrote one or two sentences in response to each of these questions: 1) What is a story? 2) Who tells stories and why? 3) Why do people respond to stories? For the first of these, we previously wrote a RACES paragraph as a group. Using that model, now students will write a RACECES (the acronym is extended to reflect two pieces of evidence) paragraph for the second question. Sentence stems will be provided to all students, but students will not be required to use them. Students should cite and explain at least two pieces of evidence in this paragraph. Students can draw ideas for their response from their own notes about the articles they have read, from responses to the bellringers in their notebooks, or from the class Timeline of Milestones in Storytelling, which will be available in students’ digital classroom and posted in the classroom. This is an opportunity to reinforce for students that we work together to build knowledge and that everyone’s contributions to the class product (i.e. the Timeline) are seen and valued.

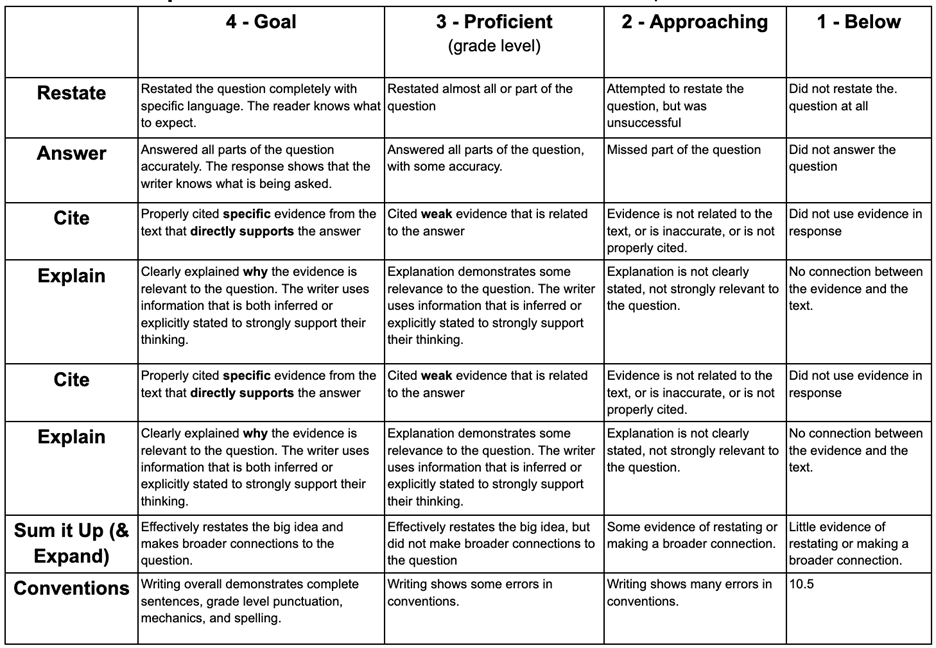

After writing this paragraph, students will swap with a peer. Each student will review the paragraph against a RACECES rubric (diagram below) to confirm that it has all the parts. Each student will also be asked to offer a specific compliment and a specific suggestion for improvement to their partner. After this exchange, students will revise this first paragraph and then go on to write a second RACECES paragraph in response to the third question from the anticipation guide.

To close out this section of the unit, students will freewrite in response to the following prompt: Describe how stories are relevant in your life. Where do you encounter stories? Which stories do you enjoy the most? What do you learn from stories? How do you use stories to communicate with other people? This task may be assigned as homework or may be done as a bellringer, depending on timing.

Figure 1. RACECES Rubric

This rubric can be used for scoring by students and teachers.