During this section, students will focus on the essential questions of 1) How are stories built? 2) Why are some stories told and retold again and again? 3) Why do stories change? Students will read and analyze the Icarus myth, followed by reading and comparing multiple versions of Cinderella. Students will analyze the story elements of character, conflict/plot, setting, and theme. When making annotations, they will focus on the Notice and Note signposts called Words of Wisdom and Again and Again. This section will take about one week, using 90-minute class blocks.

With so many stories being told in so many ways over the years, archetypes have developed for characters and plots. This reflects the qualities of a shared human experience that transcends culture and time. The Icarus myth, for example, illustrates a variety of elements that appear repeatedly in stories: a loving parent, an exuberant youth, a dramatic escape, the thrill of invention, and the despair of loss. It also incorporates several fundamental literary conflicts: person vs. self, person vs. nature, and person vs. technology. Although the details may change significantly, people in any culture and in any era would recognize the basic needs and emotions reflected in this tale. Icarus is memorable for the dramatic way in which he sailed too close to the sun, many readers can relate to the symbolism of his act of going for it, but realizing too late that he had gone too far. By the age of twelve, many middle schoolers already have experiences of their own that fit this metaphor, even if the consequences were not so dire. As a result, the story of Icarus has been retold and alluded to in countless stories, songs, paintings and poems. It even features prominently in several video games and is the source of a colloquial saying, “don’t fly too close to the sun.” These factors make Icarus a strong choice to examine when exploring the essential questions listed above.

Similarly, Cinderella is one of the most well-known fairy tales in the Western canon, with more than 500 different versions documented from around the world. This story is the inspiration for a Russian-composed ballet, a Broadway musical and many films, including the 1950 animation and ensuing “Disney princess” franchise that helped to make the Walt Disney Company a multinational giant. The Disney version of Cinderella—who is cherished by woodland critters and rides to the ball in a bedazzled pumpkin—draws most heavily from the version written by French author Charles Perrault around 1700. Around a century later, the Grimm brothers also published a widely known version in which the protagonist is called Ashputtle and receives help from a magic tree. An earlier version of the story, however, had already emerged in China by the 9th century in which fish bones play the role of the fairy godmother. Central to all Cinderella stories is the archetype of the underdog who overcomes injustice to receive her true rewards. “A real Cinderella story” has become a colloquial phrase in English to describe someone with a rags-to-riches triumph. While this thread of the story remains consistent, the varied settings and details of the retellings offer insight into different perspectives and priorities.

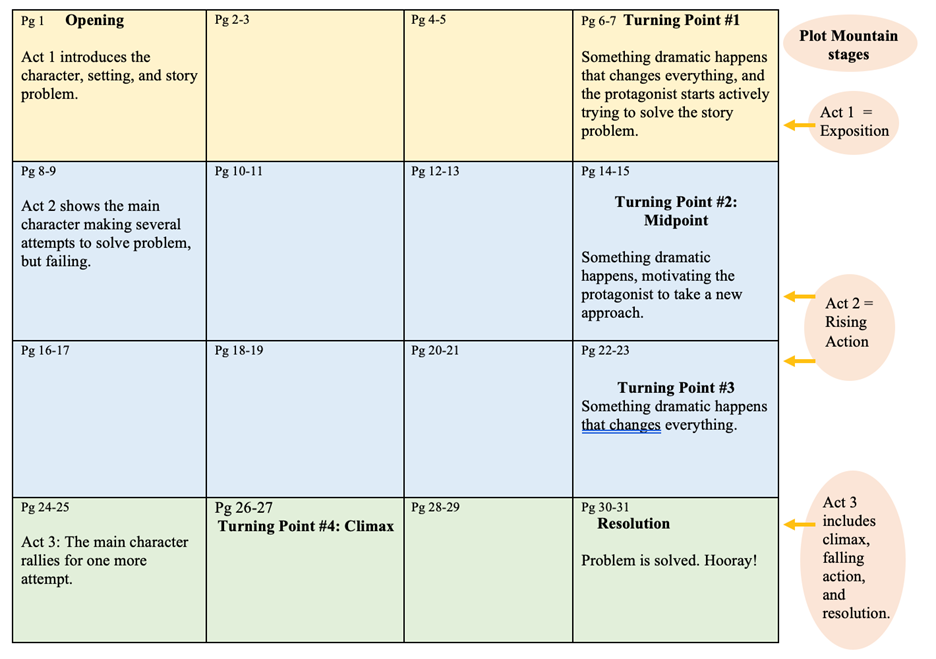

In addition to being good case studies for the relationship between characters’ actions and a story’s theme, both of these stories are classic examples of plot structure. Many textbooks present students with a “plot mountain” that divides a story into five phases: 1) exposition to introduce characters and the story problem, 2) rising action to develop the conflict, 3) the climax as the scene of most dramatic change, 4) falling action, which represents the repercussions of the climax, and 5) resolution. This simplified schematic helps students to track and talk about where characters are at in the journey of the story. In very short stories, each phase may be represented by a single scene. In longer stories, however, these phases—except for the climax—often represent multiple scenes. When examining the plot in Icarus and Cinderella, I will supplement the plot mountain by sharing with students how I view plot as an author, using “turning points” to distinguish between the major phases a story. Turning points are moments when something changes in a story so fundamentally that the characters can never go back. The climax is a turning point, but it is not the only one. The climax of Cinderella’s story is when she and the prince are brought together through his search with the shoe—which results in her promptly being whisked away from hardship to a new life in the palace. That moment could not have happened, however, without an earlier scene—when Cinderella makes a plan to attend the ball and as a result alters the trajectory of her story. Helping students recognize specific scenes as turning points will give them another tool to track character growth and the development of story meaning and themes. Turning points can be layered onto the plot mountain schematic easily, as long as the peak of the mountain is far enough over to the right to represent where the climax actually occurs in a story. (Some visuals incorrectly show the climax of the story being at the center of the plot mountain, with the exposition and rising action taking up as much visual space as the falling action and resolution).

An excellent explanation of turning points is available in Eve Heidi Bine-Stock’s How to Write a Children’s Picture Book, Volume 1: Structure. I will use the phrase “turning point” instead of her phrase, “plot twist,” because I want students to focus on these scenes as key moments of change for the characters. Each story opens with an inciting incident that sets the story problem in motion. In the plot mountain scheme, this information is part of the exposition. Next comes the first major action that propels the protagonist forward to work on the story problem. This turning point ends the exposition and kicks off the rising action of the plot mountain. The protagonist will then make multiple attempts to solve their story problem, each of which will fail. Around the middle of the story is a turning point called the “midpoint.” Here, something dramatic happens; the protagonist fails spectacularly, grows, and emerges with new fortitude to try again. In Cinderella this scene occurs right after her family leaves for the ball. Exactly what happens at that moment to cause the personal growth depends on how the story is being retold. But the end result every time is that this protagonist decides for herself she is going to the ball. Once Cinderella chooses to disobey her stepmother and pursue her own fortune, she has changed herself and her story. Another turning point occurs shortly before the climax, launching the final act of a story. In Cinderella this occurs is when her shoe is left behind, which prompts the prince to set out on his search. The climax, falling action, and resolution all occur within the third act of the story.

Picture books are a convenient format to examine these turning points in action because they are so concise. The traditional physical parameters of printing presses once meant that picture books were most commonly produced with thirty-two pages, so the storyboard in Figure 1 shows thirty-two pages with the placement of the key turning points and the five corresponding phases of the plot mountain. This diagram illustrates that turning points can generally be found at about the one-quarter, one-half, and three-quarter points in a story, and the climax occurs close to the end of the story. Understanding this can help students know where to look in a story to find the most dramatic moments of conflict and character development, which is relevant for interpreting stories and for identifying text evidence. Students can also use this information to plan out their own stories.

Although the example given here highlights the picture book genre, this structure is as applicable as the plot mountain for analyzing longer texts, novels, movies, and other genres of storytelling. This structure has a balance and rhythm that seems to be generally satisfying to human beings. We instinctively relate to the experience of a protagonist trying and failing multiple times—often in ways that feel embarrassing and prompt personal reflection and growth—before achieving their goal. If a character achieves their goal too easily, then a story is boring because it had no real struggle. If a character struggles without ever making progress, then readers get bored or frustrated. In this way, our exploration of plot reinforces the previously discussed connections that people feel when engaging with stories.

Figure 2. Plot structure on a common picture book storyboard

Except for page 1, each box below represents a double-page spread in a thirty-two paged book.

Activity 1 – Character and theme in Icarus

This lesson will begin with a bellringer, asking students to respond to the prompt: What makes a good story? For the main activity, students will read and interpret the story of Icarus. On our timeline of storytelling milestones, we will note that this myth was first written down by the Roman poet Ovid, around the dividing line between BCE and CE. When annotating the story, students will highlight the signposts Words of the Wiser and Again and Again. We will identify a theme for the story based on the choices characters make and the consequences they experience. We will add a definition for the word “allusion” to students’ notebooks and will explore how this story has been referenced in paintings, poems, and video games. Students will work in small groups to brainstorm why they believe this story has been retold so often and how they think this theme relates to their lives today. Students will freewrite in their journal relating to these questions. Resources are widely available for more detail about exploring Icarus, including a lesson plan in the HMH Into Literature curriculum for seventh grade.

Activity 2 – Character and theme in Cinderella

This lesson will begin with a bellringer, asking students to respond to the prompt: If someone was retelling the Cinderella story, what would be the most important parts for them to have in the story? Make a list below. (examples: a character who…, a shoe that…, etc. This will lead into a class conversation about what students remember about the Cinderella story and where they have seen it. For the main activity, students will read the Grimm Brothers’ version, called Ashputtle. We will read at least some of the story aloud in a reader’s theater format with students reading the words of the narrator, protagonist, and other characters. As with the previous story, we will identify themes for the story based on the choices and consequences characters face. We will also identify what values the story seems to represent. Students will work in small groups to discuss why they believe this story has been retold so often and how they think it relates to the world today. Students will complete a graphic organizer to highlight themes and supporting text evidence from this story.

Activity 3 – Analyzing Plot

As a bellringer for this lesson, students will be shown a scrambled set of five images representing key moments in the life of a butterfly. The images will show: 1) an egg on a leaf, 2) a caterpillar having just come out of its egg, 3) a chrysalis, 4) a butterfly with crumpled wings that just came out of the chrysalis, 5) a butterfly flying. Students will be asked to number the images in the order they occur. After students work individually, two students will be invited up to order two sets of the images on the board.

This will lead into a mini-lesson about the turning points of a plot being moments in a story when everything changes. Students will receive a diagram of the plot mountain and be invited to fill in the academic language associated with each phase. For some seventh-grade students, this will activate prior knowledge from previous years. On our timeline of storytelling milestones, we will mark down that the ancient Greek Aristotle wrote about plot around 300 BCE, and the plot mountain diagram comes from a German novelist in the 1800s. We will then return to the caterpillar’s story to place the turning points onto the same diagram. The egg being laid on a leaf is the inciting incident that begins this caterpillar’s quest to become a butterfly. The caterpillar emerging from the egg is first turning point, which kicks off the rising action of the story. This metaphor reinforces the significance of turning points for students because a caterpillar can’t go back into its egg even if it wanted to. In an effort to become a butterfly, the caterpillar eats and eats and grows and grows. By the middle of the story, however, it has failed to become a butterfly. Eating and growing is not enough, and the caterpillar needs to try a new strategy. At the mid-point (halfway through the rising action), the caterpillar recommits to its goal in another dramatic turning point: it sheds its skin to form a chrysalis. Although not visible to us, a lot of growth and change is happening inside that chrysalis. The next turning point occurs when the animal emerges from its chrysalis. This moment is toward the end of the rising action and prompts the third and final act of the story. Although the animal has completed its transformation into a butterfly, its story is unresolved. The climax of the story is when the animal is at its most vulnerable—having emerged from the chrysalis, but with its wings crumpled and needing time to adjust to this new state of being. At last, the resolution comes when the butterfly is fully stretched out and successfully flies away.

In class, students will receive a graphic organizer with a table that lists the turning points horizontally and has room for four stories vertically. Together, we will revisit Icarus and look for the specific scenes that represent the turning points. I will model and we will together complete the story line for Icarus. Students will then work in pairs or small groups to identify and document the turning points for Cinderella. To illustrate that this model applies to other story formats, we will watch a short animation, after which students will work together to identify the plot turning points.

Activity 4 – Cinderella revisited

In this activity, students will use picture books as mentor texts to compare different retellings of Cinderella. I will preview the different versions by reading selections aloud and showing artwork to the class. Although the picture books will remain available for students to view, each student will have their own version of the text typed out for reading and annotating. Videos of the complete stories being read aloud are also available online to support differentiation as needed. A list of stories planned for use is included in the Student and Teacher Resource section, and many other options are also available.

As they read, students will annotate for Words of the Wiser, and Again and Again. As with the Grimm brothers’ version, students will gather text evidence to support the theme of the story. They will complete the same graphic organizer that was done with the previous story, but noting the differences in the new version. They will also add a line on their plot chart to mark the turning points of the story. Students will complete this work through a combination of individual and partner work. When students have finished reading their stories, they will meet in small groups to compare their findings. In particular, students will compare and contrast the actions of the main character, and look at what values each story is emphasizing. We will look at how these different choices by authors lead to different themes. Why is it important to have stories from different voices? How does changing the setting of the story affect how it is told? Students will write RACECES paragraph responses.