Thus far, students have focused on noticing details to support their interpretation of texts. In this section, students will reorient to apply what they notice to their own writing. They will focus on the essential questions of: 1) How are stories built? 2) Why do stories change? 3) How can I build engaging stories? Students will choose a familiar tale and retell it with their own twist. Perhaps they will tell it from a different perspective or in a different setting. They will reflect on how their changes impact the story’s theme. This section is anticipated to take about a week with 90-minute blocks.

Reading like a writer means to read a text with the following questions in mind: 1) How did the writer create this story effect? 2) How can I use words to create a similar effect? Inherent in these questions is an understanding of the audience and purpose of a text. Turning our focus from interpreting stories to writing them turns students into creators. They take pride in expressing themselves and being creative. Creative writing assignments encourage students to be playful with language, which has multiple benefits. Being playful in general involves trying new ideas and taking healthy risks, which can promote community bonding and a growth mindset. Academically, being playful with language can help students expand their knowledge of syntax and diction. This can create a cycle of positive reinforcement as stronger readers become stronger writers, and vice versa. Reading like a writer is also a powerful skill that will serve students far beyond seventh grade. Writing intersects almost every career in some way, beginning with the drafting of resumes and cover letters. In addition, being able to analyze a final product and break it down into smaller components, and then to mimic those components is a valuable life skill for learning in many fields.

Activity 1: Fractured fairy tales and brainstorming

As a bellringer for this lesson, students will work with a partner to brainstorm a list of fairy tales, fables, or folk tales that they know well. I will introduce the idea of a “fractured” fairy tale by sharing with students part of a book that I wrote, called The Ugly Duckling Dinosaur. This retelling of the Hans Christian Anderson tale is set in prehistoric times, with a T. rex coming out of the egg, rather than a swan. This twist highlights that birds evolved from dinosaurs. (Dinosaurs hatched out of the same eggs as birds, have many skeletal points in common, and some even had feathers.) I’ll model for students my thinking process as an author in changing the characters, setting and events of the story to develop the twist. The original story opens by describing a farm setting, with a mother duck sitting on her nest, waiting for eggs to hatch. A neighbor duck stops by and chats about the one egg that hasn’t hatched. The opening in my story starts the same way, but set millions of years ago instead of in a farm. As a writer, I’m thinking about how that change of setting makes the story different—what other animals will readers meet? When the young T. rex emerges, how does he look, sound, and act differently from the other ducklings? I take this ugly duckling character through a series of events similar to that from Anderson’s story.

Students will then work in small groups to read aloud short scenes that are fractured fairy tale retellings. As they read, students will record on a graphic organizer what the author changed to put a new spin on the story, and what was the impact of that twist on the story’s theme. Students will choose their own fairy tale that they will retell, with their own twist. Short summaries of common fairy tales and lists of possible changes (i.e. different settings, props, character traits) will be available as a resource for students who are struggling to generate ideas. When planning their stories, students should imagine an audience that is their age or younger. Once they have chosen their tale and their twist, they will complete a series of graphic organizers to help them plan out the changes in setting, character, and plot for their tale.

Activity 2: Beginning with an “exploded moment”

As a bellringer, students will answer the question: What elements does a writer need to begin a story? We will review students’ answers, giving examples from any of the stories we have recently read together. Our list will be to introduce 1) a character, 2) a setting, 3) a conflict, and 4) a point of view through which the story will be told. Readers don’t like to be confused, and these are the core things needed for readers to feel grounded in a story. But, how can students create a scene that does all these things? Remember from our earlier reading about how our brains work, that readers like to feel like they are in a story, right alongside the characters. To accomplish this, writers use “exploded moments,” which are scenes in a story that are told with lots of detail, almost as if they are in slow motion. An exploded moment shows what a character hears, sees, thinks, feels, says, and does. This lesson is an adaptation of a lesson plan called Make a Splash! Using Dramatic Experience to ‘Explode the Moment,’ which is published on readwritethink.org by the National Council for Teachers of English. Together, we will watch a short video scene that shows how the camera zooms in to show an exploded moment on screen. Students will work in pairs to analyze a short scene from one of the texts we previously read, marking the different parts of the exploded moment with markers or colored pencils. Students will then write an exploded moment to be the beginning of their fractured fairy tale. A graphic organizer will be available as needed for students to plan out the different elements. Sentence stems will also be available that can help to introduce characters and settings. Students can also look at the opening of the original story they chose for help. As students finish their scenes, they will share with peers, who will respond to the questions: What did this writer change from the original story? What new ideas does this twist bring into the story? What do you like best about this story? Students will also check their scenes against a rubric and have time to revise.

Activity 3: Completing the story arc

As students finish their opening scenes, they will use our chart of turning points to plot out the rest of the story. Students will not write complete scenes, but rather a short description of what would happen at the different scenes. Together, the opening scene and the writing of these plot points will represent a completed story arc. Students who write more quickly than others can write an exploded moment for the climax of their story. Students will also have time built in to share their stories with peers. After reaching their final draft, students will write a reflection: What are you most proud of relating to your writing? What was challenging in creating this story, and how did you meet that challenge? What did you learn from writing this story that you will use in the future?

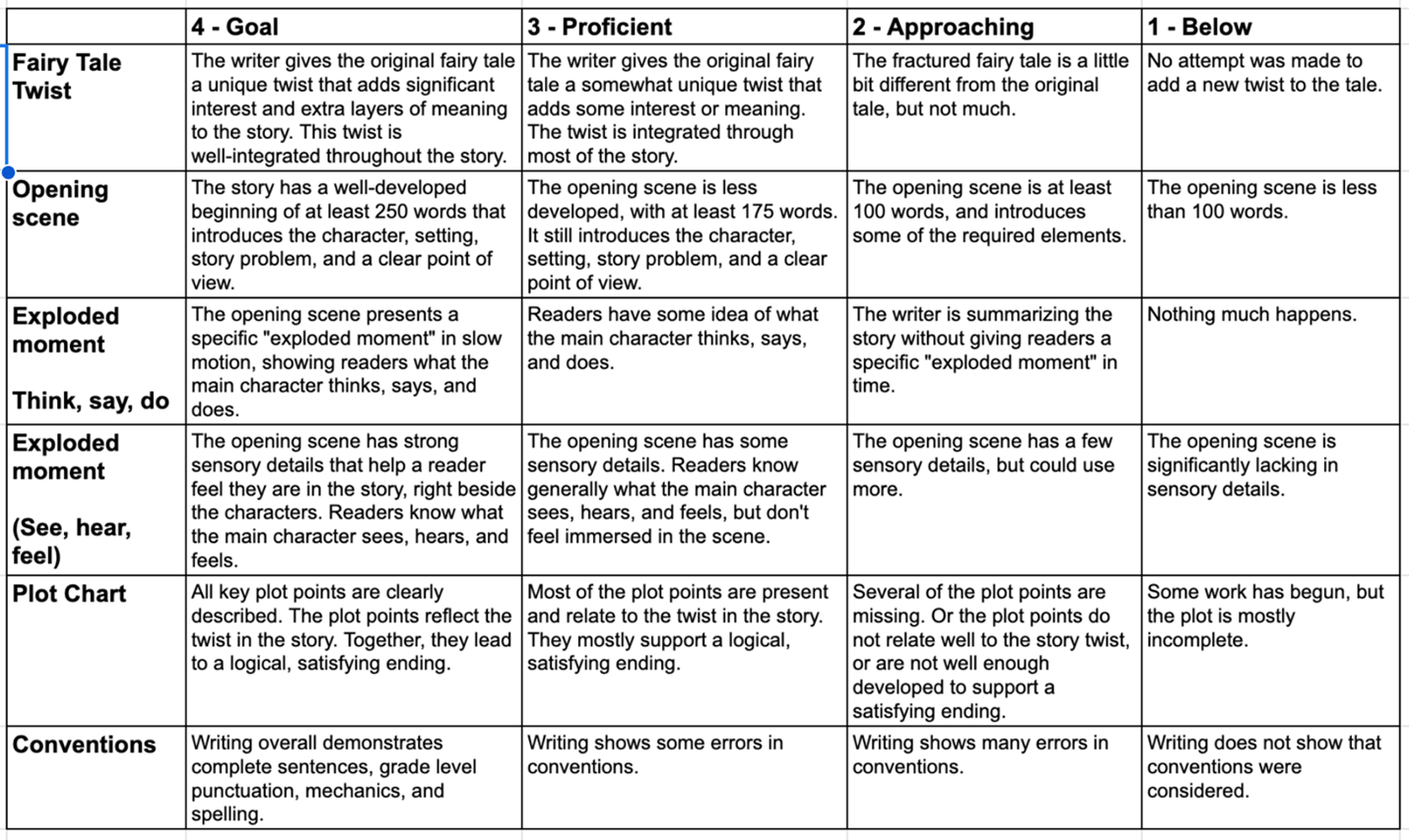

Figure 3. Fractured Fairy Tale Rubric

The story components from this section will be collectively scored with the following rubric.