Waltrina D. Kirkland-Mullins

Eating foods created by people from other countries is one of the best ways to introduce ourselves to new cultures. Doing so, however, is more than the simple sampling of new and/or unfamiliar dishes. How do the history and the availability of natural resources play into it all? How do mores and culture, class and social status, factor into food creation? Let's take look from a Korean perspective!

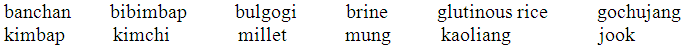

More Terms to Know

Agriculture Past & Present

Prior to World War II, tenant farming was a serious problem in South Korea. Japan's leaders exploited Korea, dominating the farming and fishing industry within the peninsula. Under Japanese rule, many Koreans lost their land and faced serious food shortages. In many instances, they were forced to grow and supply food to their colonizer. Sharecropping--where peasant farmers as tenants owned no land, yet worked the land and shared the output of food production with the land owner--discouraged innovative farming. This practice created political unrest and resulted in land reform in North Korea known as hyŏptong nongjan--or cooperative farms.)

The majority of Koreans subsisted by peasant agriculture: many Korean farmers owned small plots of land approximately 1.5 acres in size. Some served as tenant farmers (paying rent to work on the land), while others served as sharecroppers. Land was usually divided into two categories: riceland and rainfall fields. Riceland (referred to as "non") was used for the irrigation and production of rice. Rainfall fields (referred to as "pat") were used for unirrigated grain, bean crops, vegetables, and orchards. The ability to grow crops was contingent on several factors: i.e., household needs and environmental conditions like weather conditions, the availability of irrigation water, and the amount of rainfall. Oftentimes, crops had to be grown on leveled terrain and/or terraced fields, particularly for the growing of rice. Approximately two fifths of the land was used for rice cultivation. Contingent on weather conditions, the remaining land mass was used as rainfall fields.

Because of the nature of farming conditions, each household attempted to farm each type of land so they would have a wide variety of food. Among crops grown were rice, cabbage, hot peppers, radishes, garlic, lettuce, zucchini, and other squash. Barley, millet, kaoliang (sorghum), a wide assortment of beans (including soy, red, and mung), and wheat were also grown. If space permitted, persimmon, cherries, jujubes, apples, pears, peaches, or chestnut trees were planted. In addition to food crops, hemp, ramie--a type of fine grass woven into cloth, sesame, used to make cooking oil were grown in the country's southern region. On the surrounding coastal regions, peasants commonly planted sweet potatoes; in the mountainous areas, buckwheat and white potatoes were cultivated.

Animal husbandry usually took place around major cities. Today, cattle--once used primarily as draft animals--are now raised in the hundreds of thousands for slaughter. Pigs, chickens, and ducks are raised for this purpose in such regions as Cheju-do Island. Dairy farming has also emerged around major cities. Despite this trend, industrialization and urbanization has had a negative impact on the farming industry. Although large amounts of farmland exist, the number of farmers to cultivate the crops has fallen drastically over the years.

Today, most farmers plow with small tractors. Many use chemical fertilizers to control insect pests, weeds, and more. Rice productivity has increased. Grains such as wheat are purchased on the international market. In addition to animal husbandry, Cheju-do Island specializes in the production of citrus--like Mandarin oranges. As a result of this and the above-noted factors, the standard of living in rural areas has been negatively impacted and differs significantly from the progress and success of thriving, industrialized urban areas.

A Communal Event

Customarily, mealtime in the home of Korean families is a communal affair. Traditionally, males stayed out of the kitchen; women were the masters in this domain. This particularly held true when extended family reigned supreme in Korea. Today, with more nuclear families occurring as a result of industrialization and urbanization, fewer women are locked in the kitchen. Nevertheless, traditional meals were and continue to be eaten in a communal fashion: dishes are placed in the center of the table. Those gathered around the table often share their meals, sampling from one dish to the next. Knives are not used at the dinner table; when cutting slivers of beef or pork at the dinner table, scissors are used.

Social Status Determined

Traditionally, the number of food courses served as an indication of the social status of a household and its guests. In the Chosŏn Dynasty, for example, the royal enjoyed 12-13 course meals filled with assorted vegetable dishes, meats, rice, soups, and rice. Nine course meals were often served to aristocratic members (the yangban class). Their meals included at least three vegetable dishes and two salty condiments laden with hot spices, and sliced meats such as pork, chicken, and beef. Common folk were limited to 3 to 5 course meals consisting of a steamed grain, seasonal vegetables, and a bowl of soup. Today, meat is served to the yangban (aristocratic) and common folk alike.

Rice was the preferred grain for both the yangban and peasant classes. During the post-war, industrialization era, however, rice was so expensive that impoverished farmers and their families often sold it for cash and purchased cheaper grains like barley, millet, or kaoliang (sorghum).

Mealtime Etiquette

Despite modernization, mealtime is one aspect of Korean culture that has not changed. It remains a communal event. Go to a Korean eatery anywhere in the country, and you will find family and/or friends gathered around steaming bowls of stew, rice, and banchan (sidedishes) from which everyone partakes. Koreans agree that one of the best ways to share "chong"--feelings of camaraderie and love--are through sharing from a common pot or bowl. (I experienced this while attending an Episcopalian church in South Korea, where gregarious church members invited visitors to join in an after church-service repast. We feasted on buckwheat noodles laden with beef broth and vegetables, kimchi, green tea, and roasted peanuts for dessert. The experience filled the stomach and the soul).

As holds true in many cultures, rules apply at the mealtime table. Here are a few dos and don'ts Korean style: Do not begin or finish your meals before seniors are seated at the table. Use your spoon when eating rice and soup dishes; use chopsticks for side dishes. Do not pour drinks for others when you notice their beverage glasses are empty; do not pour a beverage for yourself; allow someone else to pour your drink for you. Use fingers ONLY when eating wrapped-leaf dishes; otherwise use chopsticks. When dining out, do not tip the waiter or waitress; tipping is considered offensive.