The idea of a language of symbols is not new. Cave drawings and Ice-Age wall drawings from 27,000 years ago were considered to be the first attempts at primitive language.

3

This language used visual symbols to convey ideas. Much later, in the 17

th

-century philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz was the first to imagine a full writing system in which images could be used to describe all human communication. Gottfried envisioned a writing system that did not need to be translated and was understood by a global community. The idea of a universal language that was likened to mathematics and music was original indeed.

4

The thought of communicating with images in order to access a vast audience was clearly developing. Later in the early 1920s, Otto Neurath, a forward-thinking Viennese philosopher, wanted to create an exhibition of public information that was visually appealing and easily understood by the multicultural Austrian community, so he began working on a pictorial system that could be used to communicate and be understood by a widely diverse population. Needless to say, the exhibition was a huge success. His work evolved to become an International Picture Language, publishing a book in 1936 called the

International System of Typographic Picture Education,

which reflected the international philosophy of this new system.

5

The images of this pictorial system were named isotype. So valuable was their work that Otto and his wife Marie Neurath founded the Isotype Institute in 1941 in Oxford, England. The Neuraths' commitment to international communication was reflected in their goals for the institute, which were the promotion of a visual education for children and underdeveloped countries.

6

The Neuraths' idea of a visual education system crossing political, social, cultural, and language boundaries was visionary, and they clearly understood that images communicate ideas and thoughts when words could not. They were pioneers, indeed, realizing the significance of the development of this visual method that would communicate ideas quickly, easily, and clearly to so many. The Neuraths' groundbreaking ideas are continuing to develop today and were addressed recently in an article "Think Visual" by Clive Thompson in which he emphasized the importance of thinking and communicating visually. He suggested that a picture language is precisely what we need to solve the world's biggest challenges like global warming and economic reform. These innovative thinkers--Leibniz, the Neuraths and Thompson-- understood that visual explanations can communicate multifaceted concepts and problems clearly and effectively to a diverse population so that everyone can have the same mental image of a concept /problem

7

and thus begin solve it.

More recent brain research has proved that the characteristics of the left and right side of the brain and the way each side processes information, both separately and together, are particularly significant in their support for the use of visual symbols to communicate ideas. The right and left sides of the brain work both independently and together.

8

The left side of the brain has been characterized as being verbal, analytical, male, dominant and scientific, by David Crow

9

and logical, mathematical, symbolic, pattern-using, and dominating the right brain by Robert H. Williams.

10

The right side of the brain is characterized as visual, female, non-verbal by David Crow, and creative, pattern-seeking, visual-pictorial, and pattern-creating by Williams. In an attempt to learn more about each side of the brain, doctors devised ways to test brain split patients, whose surgery to reduce seizures cut the links between the left and right brains. When working independently, the split-brain patient, "allowed to see a picture with only the left-brain visual field," could tell the researcher, "This is a picture of a cow." But if the patient saw the same picture with only the right brain visual field, he could not speak about it at all. Yet he could point to a similar picture of a cow showing that he had recognized the image.

11

This research supports a conception of the unique abilities of each side of the brain. It would also suggest that the visual symbol would be read by the left side of the brain in a logical way to direct thinking, but that it would also be viewed creatively by the right side of the brain, opening a pathway to the possibilities and ideas the image might evoke. Both sides of the brain working together could produce the best processing of information.

More recently, Dr. Glen Johnson, a neuropsychologist, asserts in his research described in his book,

Traumatic Brain Injury Survival Guide 2010

, that the brain compares to an orchestra, not one big computer as was previously accepted, but really like a million little computers all working together. The left hemisphere and right hemisphere each have separate and unique jobs; two sides of the brain, two different jobs. When we see, each hemisphere processes half the visual information. Visual information that we see on the left gets processed by the right hemisphere. Information on the right gets processed by the left hemisphere. Remember, wires that bring in information to the brain are 'crossed'--visual information from the left goes to the right brain."

12

Thus, visual images engage both sides of the brain. For example, when a thought bubble is viewed, the right side of the brain, the creative, pattern maker, will process the image and recognize it--"that's a thought bubble"--and then send it to be processed by the left side, the analytical, logical, language, pattern seeker to make sense and meaning of the world, to fill the thought bubble with language, words that make meaning of the image within the given context given .When both sides of the brain are fully engaged in processing information, they are uniting the sum of their unique interpretations of information, communicating by unleashing their individual potential. I suggest that this synergy is the power of the visual image. As teachers, what better way can we engage our students than to promote their ability to access their thinking fully, using both sides of their brains?

13

Brain sparks begin to fly, as both the right and left hemispheres are fully engaged in the conversation of creation, as the words inspired by symbols begin painting a visual image of their own.

Based upon the research that indicates that visual images engage both the left and right hemispheres, it would seem apparent that symbols are excellent teaching tools. When a visual image promotes thinking, particularly when the image encourages one to think about and apply written language. Robert Marzano, in his writing

Classroom Instruction that Works: Research Based Strategies

, states that the more we use both systems of representation, linguistic and non-linguistic, the better we are able we are to think about and recall knowledge. "It has been shown that explicitly engaging students in the creation of non-linguistic representations stimulates and increases activity in the brain."

14

Marzono's findings support those of Williams and Dr. Johnson's findings regarding brain activity associated with reading images and symbols. As Marzono emphasizes, the most underused instructional strategy is creating non-linguistic representations to help students understand content in a whole new way."

15

When we use visual images to think about and promote writing, we are using non-linguistic representations to create linguistic representations, engaging both sides of the brain and creating a way for students to use their full thinking potential.

Finally, in

Visual Explanations

, Edward Tufte discusses the extraordinary ways in which visual images can be used to describe and explain complex ideas, and he provides examples of brilliantly creative ways that images can be used to represent information clearly and effectively. He describes how visual explanations can be used as a method to describe, illustrate and construct knowledge, comparing clarity and excellence in thinking to clarity and excellence in representation, an act of insight.

16

Imagine the implication for the use of visual images in the classroom, as these symbols explain complex information, constructing knowledge and insight, and thus crossing barriers of communication when words cannot. The use of symbols and images that explain complex ideas would be far reaching, indeed. Thus the Trait Mate can explain characterization and story elements by providing clarity for students as they use the image to think.

Birth of the Trait Mate

In an effort to provide support for my students as they tried to think about their writing more strategically, with the necessary structure, character description, elaboration, and organization, I began a search. I searched the Internet. I searched libraries, and I searched professional resources for tools or graphic organizers that would help my students to write with the needed structure and elaboration that were asked. Since these writing elements are fundamental to stories in both reading and writing, I thought the task would be easy. However, this was not the case. What I found were organizers that were sterile, flat, and boring. I found organizers with lines--lines in different directions, lines in boxes, lines in boxes with headings, and lines in different shaped boxes. Surprised and disappointed, I knew these kinds of thinking tools would neither promote nor direct thinking about writing or inspire one to do either. I was looking for was a tool that was interesting, inspiring, and engaging while directing and supporting students to think systematically about their writing. I was unable to find anything that provided this specific structure and elaboration. I was looking for a tool that would lead their thinking to create more fully developed characters and events in a narrative. How could I help my students to remember that they needed to describe a character fully in each of the story event? How could I help my students to describe a character specifically through his/her thoughts, actions, feelings, dialogue, character traits, and how others in the story responded to him/her? That was my frustration as well as my challenge!

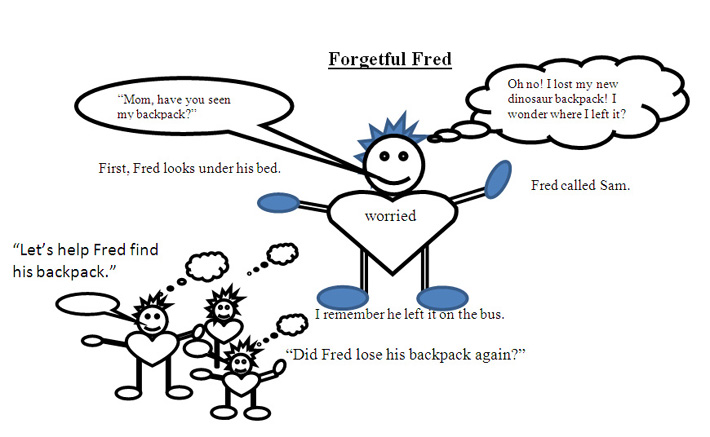

I began talking with my students to explain how I wanted them to describe a character in a story. I was explaining the importance and value of this kind of description when writing a story, for yet another time! When I saw their blank stares, I began to draw. I drew visual images. They immediately perked up. I had captivated their attention and interest! My students were able to connect more easily and clearly to the idea that these images were conveying than with what I had been trying to explain in words on many occasions. So, I continued to draw. I drew a "BIG" heart to symbolize the importance of describing the character's feelings. Then I drew a circle with a face on the top of the heart; it was the symbol I had assigned to character traits. It was beginning to come alive! Next, I drew a thought bubble to symbolize the importance of including thoughts and a speech bubble to symbolize the need for the character's dialogue. Finally, I drew little people to symbolize the importance of showing how other characters respond to the main character. Thus was born what I call the "Trait Mate." This friendly little guy embodies the elements my students needed to use as they described their characters. One symbol communicated all this information. A picture can speak a thousand words and sometimes far better than I!