Water safety and quality are fundamental to human development and well-being. Providing access to safe water is one of the most effective instruments in promoting health and reducing poverty. As the international authority on public health and water quality, World Health Organization (WHO) leads global efforts to prevent transmission of waterborne disease.

12

In 2010, the UN General Assembly recognized access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right and called for international efforts to help countries to provide safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation.

13

In 2015, 71% of the global population (5.2 billion people) used a safely managed drinking-water service – that is, one located on premises, available when needed, and free from contamination. As much as 89% of the global population (6.5 billion people) used at least a basic service, characterized as an improved drinking-water source within a round trip of 30 minutes to collect water.

Yet still, poor access to treated water remains a global problem. As many as 844 million people lack even a basic drinking-water service, including 159 million people who are dependent on surface water. By 2025, half of the world’s population will be living in water-stressed areas.

14

Conditions are most severe in sub-Saharan Africa, where 42% of the population is without improved water, 64% is without improved sanitation, and deaths due to diarrheal diseases are greater than in any other region.

15

The health toll caused by the lack of access to treated water affects millions. Inadequate management of urban, industrial, and agricultural wastewater means the drinking-water of hundreds of millions of people is dangerously contaminated or chemically polluted. At least 10% of the world’s population is thought to consume food irrigated by wastewater. Poor sanitation is linked to transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio.

16

Diarrhea remains a major killer but is largely preventable. Approximately 842,000 people in low- and middle-income countries die each year because of inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene each year, representing 58% of total diarrheal deaths. Poor sanitation is believed to be the main cause in some 280,000 of these deaths.

17

Since 1990, the number of people gaining access to improved sanitation has risen from 54% to 68% but some 2.3 billion people still do not have toilets or improved latrines. In low- and middle-income countries, 38% of health care facilities lack an improved water source, 19% do not have improved sanitation, and 35% lack water and soap for handwashing. Globally, 15% of patients develop an infection during a hospital stay, with the proportion much greater in low-income countries.

18

There are several obstacles to overcome for these conditions to improve these circumstances:

Economic and social effects

When water comes from improved and more accessible sources, people spend less time and effort physically collecting it, meaning they can be productive in other ways. This can also result in greater personal safety by reducing the need to make long or risky journeys to collect water. Better water sources also mean less money spent on health, as people are less likely to become sick and have medical costs and can remain at work. With children most vulnerable to water-related diseases, access to clean water can result in better health and better school attendance, with positive longer-term consequences for their lives.

Challenges to Implementing Water treatment in the Developing World

Climate change, increasing water scarcity, population growth, demographic changes and urbanization already pose challenges for water supply systems. Re-use of wastewater, to recover water, nutrients, or energy, is becoming an important strategy. Many countries are using wastewater for irrigation – in developing countries this represents 7% of irrigated land. Safe management of wastewater can yield multiple benefits, including increased food production.

19

Options for water sources used for drinking water and irrigation will continue to evolve, with an increasing need to use groundwater and alternative sources, including wastewater. Climate change will lead to inconsistency in harvested rainwater. Management of all water resources will need to be improved to ensure quality. Certainly, a major set of obstacles continue to the lack of financial and political investment and the difficulty in maintaining appropriate services. Governmental and financial instabilities do affect the movement forward in this endeavor for clean water for everyone. Collaboration between water, health and education groups involved in community-based research can demonstrate cost efficient, locally manageable options for water and sanitation services.

20

Water Treatment Methods for Developing Countries

Many rural residents and people living in low- and middle-income countries still collect water from rivers, lakes, ponds and streams contaminated with human and animal waste, whether from open defecation or other problems such as seepage from septic tanks and pit latrines.

21

People with access to cleaner water from common wells, collected rainwater or centralized sources face the risk of pollution - even when a water source is deemed “safe,” poor hygiene during collection, storage and handling of water results in contamination.

22

A focus for researchers should be in developing strategies on the sustainability of water and sanitation services regarding the environment, culture, and economics of the area and attempting to provide implementation of long-term solutions for water treatment systems. Solutions could include low-cost household technologies as opposed to centralized systems.

Centralized treatment systems are generally difficult and expensive to maintain. Because of the many issues involved in not only implementing but affording and managing these systems, groups such as UNICEF and the WHO have long recognized that the most practical immediate strategy for improving rural drinking water quality is to provide solutions at the household level. Household water treatment and safe storage (HWTS) technologies are designed to improve water quality at the point-of-use (POU). The WHO published specifications for evaluating the microbiological performance of different HWTS systems in 2011, which established target performance levels for bacteria, virus and protozoa in POU water treatment, providing a benchmark for measuring effectiveness of the designs.

23

One common POU solution involves chlorination — essentially the same treatment used to disinfect public water supplies in the early 1900s. Under this model, diluted sodium hypochlorite is manufactured locally, bottled and added to water by the capful for disinfection. The water needs to be agitated and then sit 30 minutes before drinking.

24

Another household water treatment is solar disinfection. This approach requires users to fill plastic soda bottles with low-turbidity water, shake them for oxygenation and place them on a roof or rack for six hours in sunny weather or two days in cloudy conditions. Ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun works together with increased temperature to inactivate microbial pathogens in the water.

The pros for each of these methods include ease of use, virtually no cost and effective pathogen reduction. The cons include the need to pretreat even slightly turbid water, long treatment times, especially in cloudy weather, the need for a large supply of clean bottles and the limited volume of water that can be treated at one time.

Most other POU options involve some form of filtration designed to remove pathogens by passing water through a variety of natural materials. Clay-based ceramic filters, for example, remove bacteria through micropores in the clay and other materials such as sawdust that are added to improve porosity. The best-known design in this category is a flowerpot-shaped device that holds eight to 10 liters of water and sits inside a 20- to 30-liter plastic or ceramic receptacle, which stores the filtered water.

25

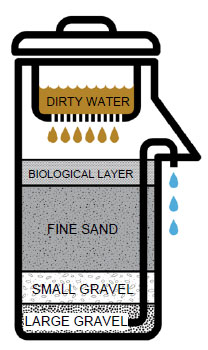

Slow sand filters remove pathogens and suspended solids through layers of sand and gravel. One common household design, the Biosand filter, consists of a concrete container incorporating layers of large gravel, small gravel and clean medium-grade sand. Prior to use, users fill the filter with water every day for two to three weeks until a bioactive layer resembling dirt grows on the surface of the sand. A diffuser plate is used to prevent disruption of the bioactive layer when water is added. Microorganisms in the bioactive layer consume disease-causing viruses, bacteria and parasites, while the sand traps organic matter, particles, and any remaining pathogens. Users simply pour water in the top and collect water out of an outlet pipe. The flow rate can be maintained by cleaning the filter by agitating the top layer of sand and by pretreating turbid water before filtering.

26

Basic diagram of a concrete Biosand filter from ohorizons.org