Classification of Goods and Resources within the Product Market

The product market is divided into the production of four types of goods: public goods, private goods, common resources, and club goods (goods produced by natural monopolies). The classification of a good depends upon two characteristics: whether the good is rival or non-rival and whether the good is excludable or non-excludable.

Rival goods

are goods in which the consumption by one consumer decreases the total quantity available. Each unit of the good can only be used once. These goods are often known as zero-sum goods; one person cannot gain (+1) without another losing (–1).

Excludable goods

are goods that are not available to everyone, usually due to cost or regulation. Goods that aren't free are considered excludable because you can only use or have the good if you are willing to buy it.

Goods that are both rival and excludable are known as

private goods

. Because producers usually produce a limited supply (or simply because there are limited resources and unlimited wants), most goods (especially in a capitalist society like that of the US) are private goods. Examples may include the clothes you wear, the x-box you got for Christmas last year, the food you eat, the car you drive, and the house you live in. The rival nature of private goods is easily seen during the holiday season when parents wait for hours outside Toys 'R Us on Black Friday for this year's "hot toy" only to find that the person in front of them got the last one. Some stores might even mark-up the toy, reiterating the exclusive nature of the product.

Goods that are rival, but non-excludable are known as

common resources

. Common resources display the same limitations to supply that are characteristic of most goods we consume, but are available to everyone. Free samples, fish stocks in the ocean, and campsites at a free public park are all examples of common resources.

Club goods

are those goods and services produced by natural monopolies and are non-rival, but excludable. Some of the best examples we have come in the form of cable television, the Internet, toll roads, and bridges. Each of these services can be offered to as many people as are willing to pay for the right to use the service.

Public goods

are those goods and services that are both non-rival and non-excludable; they are available to everyone and one person's use does not prevent someone else's use. Examples of public goods might include parades, monuments, public roads, education, and national defense. Notice that most of these goods and services are offered free to the public by the government. These goods are often referred to as "social goods" because the government provides them to meet certain social needs of the public.

Some goods don't fit squarely into one of the four classifications of goods. Private goods that produce externalities are known as

mixed goods

.

Externalities and Social Efficiency

Externalities are costs or benefits of a good or service that are experienced by someone other than the person consuming that good or service. Two types of externalities exist: positive and negative.

The benefits someone receives from consuming one additional unit of a good is known as the marginal private benefit, often abbreviated MB.

Positive externalities

are the benefits others gain from someone consuming a product. For example, say that every child at your school has received a flu vaccine except you. The chances that you will catch the flu diminish greatly because everyone else has been vaccinated; if no one else can get the flu, who can give it to you? Let's say your neighbor plants a bunch of aromatic flowers in her garden. During the spring the flowers bloom and produce a beautiful aroma enjoyed by the entire neighborhood. Since only your neighbor paid for the good, everyone else is receiving a free benefit. These benefits are known as "social benefits." People that enjoy social benefits without paying for them are known as

free riders

.

The costs someone assumes from consuming one additional unit of a good is known as the marginal private cost, often abbreviated MC.

Negative externalities

are costs to others beside those consuming the good. Examples include pollution, secondhand smoke, potholes, noise pollution, traffic, and light pollution. Negative externalities are often referred to as "social costs."

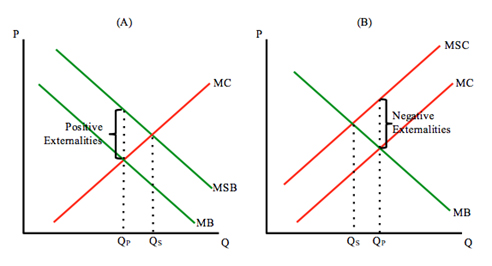

Marginal social benefits (

MSB

) and marginal social costs (

MSC

) are the marginal total benefits and costs, respectively, received by consumption of the next unit of the good. Specifically, MSB = MB + positive externalities; that is, the marginal social benefit is equal to the marginal benefit received by the consumer of the good plus the social benefit received by any free riders. MSC = MC + negative externalities; that is, the marginal social cost is equal to the marginal cost received by the consumer of the good plus the social cost received by the rest of society. Because MSB is comprised of the private and social benefits, MSB > MB. Similarly, MSC > MC. This relationship is depicted in Figure 1.

Social efficiency

is a balance between the private sector of a market and society and must be viewed from two angles. Where positive externalities exist, social efficiency occurs where the private costs balance out the additional benefits received by society; that is, where MSB = MC. If MSB > MC, as seen in Figure 1A, there exists an incentive for society to increase production until social efficiency is reached at a quantity of Q

S

. Where negative externalities exist, social efficiency occurs where the private benefits balance out the social costs; that is, where MSC = MB. If MSC > MB, as seen in Figure 1B, there exists an incentive for society to decrease production until social efficiency is reached at a quantity of Q

S

. Due to the nature of these relationships, we can assume that goods and services that produce positive externalities are naturally under-produced by the private sector (illustrated in Figure 1A as Q

S

> Q

P

) while those that produce negative externalities are naturally over-produced by the private sector (illustrated in Figure 1B as Q

S

< Q

P

).

Government Regulations

How is social efficiency achieved if its level of output differs from the natural level of output produced by the private market? Back in 1776, economist Adam Smith suggested that the best way to regulate a market was to leave it alone and let the market self-regulate: the invisible hand of supply and demand would govern markets. Depending upon what political side of the economic spectrum you lie, you may have varying opinions about the extent to which governments should be involved. This debate is left for discussion in AP United States Government and Politics. AP Microeconomics, given no political affiliation, studies the government's ability to regulate these markets. We will focus our attention on the two main types of government regulation: taxes and subsidies.

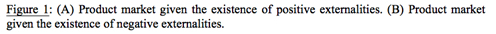

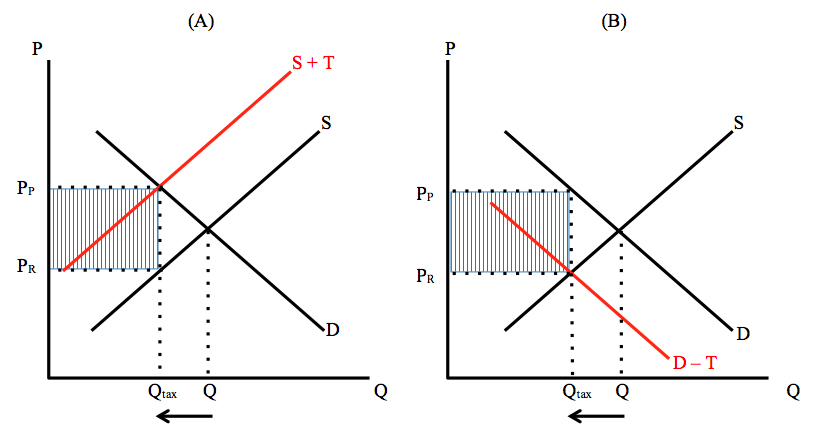

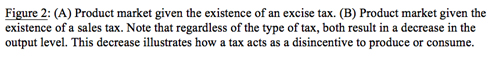

Taxation

is a government regulation in which the government collects money for the production or consumption of a good or service. The tax is meant to serve as a disincentive to either produce or consume as it essentially increases the cost. Many types of taxes exist. We will, however, only focus on excise and sales taxes. An

excise tax

is a tax to the producer of a good or service. A

sales tax

is a tax to the consumer of said good or service. You might recall from our study of elasticity that both the consumer and producer, regardless of who is actually being taxed, share the tax burden. This is evident by changes in the consumer and producer surplus. Figures 2A-B illustrate the effects of a tax on the quantity supplied and demanded within the market.

Remember that the supply curve represents the lowest combination of prices that a producer is willing to sell its product for at a given level of output. Therefore, an excise tax is depicted at (S + T). For a producer, an excise tax is similar to the price of an input increasing, which explains why the (S + T) curve resembles a decrease in supply. Conversely, demand represents the highest combination of prices that consumers are willing to purchase a product for at a given level of output. A sales tax is thus depicted as (D – T). For a consumer, a sales tax is similar to a decrease in income, which explains why the (D – T) curve resembles a decrease in demand.

To understand why the decrease in output in the market occurs, one must understand what happens to individual firms. When a tax is incurred, the new equilibrium price is not the price received by the firm (P

R

), but rather the price paid by the consumer (P

P

). The price received by the firm is actually lower at P

R

, where the new equilibrium quantity hits the original supply curve. The shaded region between S and (S + T) is the tax amount collected by the government. Because price falls, the marginal revenue (MR) for individual firms also falls.

Excise taxes have further sub-classifications: per-unit and lump sum. A

per-unit tax

is a tax on each unit a firm produces while a

lump sum tax

is a single tax payment whose value is not determined by the total quantity produced by the firm. The type of excise tax often depends on policy makers and which type they believe they can get passed and which type would serve as a more effective disincentive to produce. What is the economic effect on companies? Per-unit taxes primarily affect the marginal cost (MC) while lump sum taxes affect the fixed costs (FC).

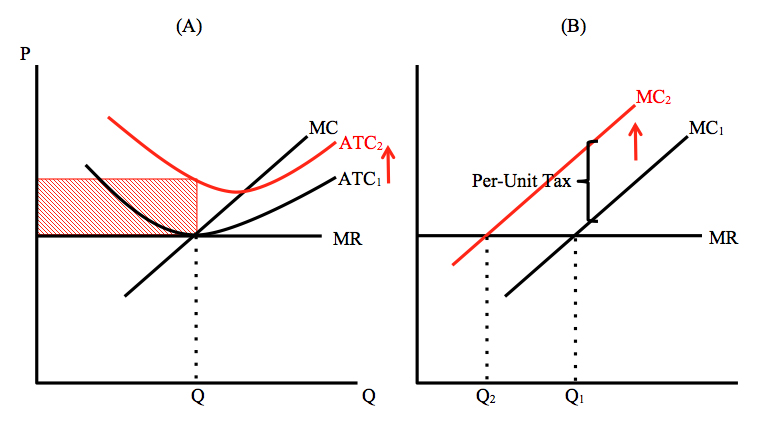

Since the lump sum tax (depicted in Figure 3A) only affects a firm's profits by increasing the average total cost (ATC = AFC + AVC), no decrease in an individual firms' output is seen. The decrease in profits may serve as an incentive for some firms to leave the market, which would decrease the overall level of production in the market. If nothing else, the decrease in profits would at least serve as a deterrent for other firms to enter the market, thereby slowing the production of the good or service.

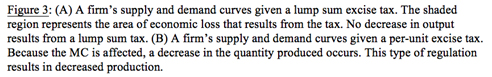

Figure 3B illustrates the effects of a per-unit tax on the firm. Remember that profit maximization occurs where MR = MC. Because a tax increases the MC curve, the profit-maximizing level of output falls (the desired effect of the tax).

Subsidies are a government regulation in which the government pays money for the production or consumption of a good or service and have the opposite effect as a tax. The subsidy incentivizes production or consumption by decreasing the cost. Like with taxes, however, the way in which a subsidy will affect the cost depends on whether the subsidy is either a per-unit or lump sum subsidy. As with taxes, the government can choose to subsidize either the producer or the consumer. Unlike a tax, however, the per-unit subsidy decreases the MC and the lump sum decreases the FC, and in turn, the ATC. Both the per-unit and lump sum subsidy result in an increase in the level of production.

Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) and Externalities

Greenhouse gases are chemical compounds that allow sunlight to freely enter Earth's atmosphere. Carbon dioxide is the most widely thought of GHG. Carbon dioxide and the other GHGs are natural components of the atmosphere, but when their levels build up, the gases absorb more infrared radiation and trap heat in the atmosphere causing the planet's temperature to slowly rise.(1) This reaction is known as the Greenhouse Effect and has caused the earth's average temperature to rise by 1.4

o

F over the last century.(2) While carbon dioxide concentrations are naturally regulated by the carbon cycle, human activities that release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere disturb the cycle and are the largest contributors to the Greenhouse Effect.(3) If humans continue to pump high levels of carbon emissions into the atmosphere (through activities like driving), scientists expect Earth's temperature to rise by another 2-11.5

o

F over the next century.(4)

The invention of the automobile has been one of the primary facilitators of economic growth and sprawl. Because of the relative cheapness and availability of cars, urban sprawl has increased dramatically. According to a report from the 2012 US census, 8.1% of Americans have commutes of 60 minutes or longer.(5) With increased sprawl comes an increased dependence on fossil fuels like petroleum, which is a well-known source of greenhouse gases. In fact, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 28% of greenhouse gas emissions in 2011 can be attributed to automobiles.(6) Greenhouse gas emissions from transportation have increased by about 18% from 1990-2004.(7)

Gasoline consumption is a primary contributor to the increase of GHGs and consequently global climate change. Drivers are the single largest source of GHG emissions worldwide, accounting for approximately 22% of all human-generated emissions.(8) Carbon dioxide can linger in the atmosphere for around a century, so the effects of US emissions will easily be felt for generations. Clifford Cobb, author of "The Roads Aren't Free," estimates the damage caused by US emissions to be around $66 billion each year.(9)

Temperature change greatly affects the world's climates, which can in turn have devastating effects to society. Ocean temperatures rise at a much slower rate (0.18

o

F over the last century) than temperatures on land, but marine ecosystems tend to be more sensitive to these changes. Coral, which provides a marine habitat for countless sea creatures, is more likely to die off as ocean temperatures rise. Krill, a major food source at the base of the food chain, reproduce at a slower rate. As food sources are affected, larger predators are affected, and human food sources become less prevalent. Invasive species and marine diseases are also more likely to spread.(10)

Apart from affecting the environment and food sources, climate change can have serious health implications within the human population. In 2003, Europe experienced its worst heat wave in probably 500 years with nearly 22,000-45,000 heat-related deaths.(11) Heat related deaths are expected to increase in number as more cities become urban heat islands (areas with "increased heat storage and sensible heat flux caused by the lowered vegetation cover, increased impervious cover and complex surfaces of the cityscape").(12) Additionally, global warming directly impacts crops, as rising temperatures are generally associated with more frequent drought. Elevated temperatures can also change the ecology of plant pathogens. But the spread of disease is not only a concern for food crops, but for humans more directly as well. According to Jonathan Patz, author of "Impact of Regional Climate Change on Human Health," disease-spreading organisms have lifespans and reproductive functions that are affected by temperature. As temperatures increase, organisms like protozoa, bacteria, and viruses reproduce and spread more rapidly. The World Health Organization, using the Hadley Centre Global Climate Model, has estimated that the "climate-change-induced excess risk of the various health outcomes will more than double by the year 2030 (Patz, 314).

The societal and environmental impacts of global warming are vast. So what steps is the government taking to help eliminate these negative externalities? How can the government help the producer and consumer externalize intrinsic costs to society? Taxation is the obvious regulation, and yet fossil fuel subsidies abound.

Government Regulations Support Fossil Fuels?

The United States government attempts to regulate the energy market using several of the economic concepts discussed earlier. For example, consumers and producers can both receive subsidies (tax breaks) for green efforts like purchasing fuel-efficient cars. But not all government regulation is efficient. In fact, many regulations intend to provide improvements to the standard of living without regard to maximizing the allocatively efficient usage of our limited resources; that is, they don't weigh the marginal costs to society against the marginal benefits to society.

The government continues to subsidize driving, petroleum and other fossil fuels despite the negative impacts associated with increased carbon dioxide emissions. Why? Because Americans have become so dependent on automobiles, the government feels obliged to keep gas prices as low as possible. To accomplish this task, the government subsidizes the protection and reservation of foreign oil for American consumption. By protecting American rights to foreign petroleum, America is able to reduce foreign competition for resources and keep prices lower. Another way in which the government attempts to protect the American consumer is to maintain a large petroleum reserve. The US Strategic Petroleum Reserve is the world's "largest stockpile of government-owned emergency crude oil" with approximately 727 million barrels on reserve.(13) This stockpile is meant to protect the American consumer from exorbitant price hikes in the case that international supplies become unavailable for some reason. In 1999 when gas prices ranged between $0.94 and $1.22 with an average cost of $1.13 in the US,(14) Cobb estimated gas prices to be subsidized by approximately $1.60 per gallon of gasoline,(15) subsidizing gasoline by more than 50% of the cost.

According to a study completed by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) from 2002-2008, the federal government provided almost 2.5 times as many subsidies for fossil fuels ($72 billion) than for renewables ($29 billion).(16) One of the biggest distinctions the ELI draws between subsidies for the two types of energy is that those for fossil fuels were long term and written into the US Tax Code as permanent provisions while those for renewables were short term, time-limited initiatives that had to be implemented through other energy bills.

The government provides what many would consider to be contradicting policies. On one hand, the government wants to increase productivity by lowering the cost of transportation and allowing its citizens to commute to work, but on the other hand, the government is also responsible for the social welfare of its citizens. But how do we measure the quality of life? What is the cost of our futures?

Specialists agree that simply taxing gasoline or removing the currently existing subsidies will have negligible effects on the demand for petroleum in the long run. Instead, such regulations would promote innovation of more fuel-efficient cars. Americans would still be highly dependent on fossil fuels, however.