Guide to Curriculum Units

by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute

2011

Contents

- Preface

- I. Writing with Words and Images

- II. What History Teaches

- III. The Sound of Words: An Introduction to Poetry

- IV. Energy, Environment, and Health

Preface

In March 2011, forty-four teachers from nineteen New Haven Public Schools became Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute to increase their preparation in their subjects and to develop new curricular materials for school courses. Established in 1978, the Institute is a partnership of Yale University and the New Haven Public Schools, designed to strengthen teaching and improve learning of the humanities and the sciences in our community's schools. Through the Institute, Yale faculty members and school teachers join in a collegial relationship. The Institute is also an interschool and interdisciplinary forum for teachers to work together on new curricula.

The Institute has repeatedly received recognition as a pioneering model of university-school collaboration that integrates curriculum development with intellectual renewal for teachers. Between 1998 and 2003 it conducted a National Demonstration Project to show that the approach the Institute had taken for twenty years in New Haven could be tailored to establish similar university-school partnerships under different circumstances in other cities. An evaluation of the Project concluded that new Institutes following the Institute approach could be rapidly established. Based on the success of that Project, in 2004 the Institute announced the Yale National Initiative to strengthen teaching in public schools, a long-term endeavor to influence public policy on teacher professional development, in part by establishing exemplary Teachers Institutes in states throughout the country. In 2009 An Evaluation of Teachers Institute Experiences established that such Institutes promote precisely the teacher qualities known to improve student achievement and epitomize the crucial characteristics of high-quality teacher professional development. Moreover, Institute participation is strongly correlated with teacher retention. In New Haven, Institute participants were almost twice as likely as non-participants to remain in teaching in a New Haven public school.

Teachers had primary responsibility for identifying the subjects on which the Institute would offer seminars in 2011. Between October and December 2010, Institute Representatives canvassed teachers in each New Haven public school to determine the subjects they wanted the Institute to address. The Institute then circulated descriptions of seminars that encompassed teachers' interests. In applying to the Institute, teachers described unit topics on which they proposed to work and the relationship of those topics both to Institute seminars and to courses they teach. Their principals verified that their unit topics were consistent with district academic standards and significant for school curricula and plans, and that they would be assigned courses in which to teach their units in the following school year. Through this process four seminars were organized, corresponding to the principal themes of the Fellows' proposals. Between March and July, Fellows participated in seminar meetings, researched their topics, and attended a series of talks by Yale faculty members.

The curriculum units Fellows wrote are their own; they are presented in four volumes, one for each seminar. A list of the 200 volumes of Institute units published between 1978 and 2011 appears after the units. The units contain five elements: objectives, teaching strategies, sample lessons and classroom activities, lists of resources for teachers and students, and an appendix on the academic standards the unit implements. They are intended primarily for the use of Institute Fellows and their colleagues who teach in New Haven. They are disseminated on Web sites at yale.edu/ynhti and teachers.yale.edu. Teachers who use the units are encouraged to submit comments at teachers.yale.edu.

This Guide to the 2011 units contains introductions by the Yale faculty members who led the seminars, together with synopses written by the authors of the individual units. The Fellows indicate the courses and grade levels for which they developed their units; many of the units also will be useful at other places in the school curriculum. Copies of the units are deposited in all New Haven school libraries. Guides to the units written each year, a topical Index of all 1819 units written between 1978 and 2011, and reference lists showing the relationship of many units to school curricula and academic standards are online at yale.edu/ynhti.

The Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute is a permanently endowed academic unit of Yale University. The New Haven Public Schools, Yale's partner in the Institute, has supported the program annually since its inception. The 2011 Institute was supported also in part by a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The materials presented here do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

James R. Vivian

New Haven

August 2011

I. Writing with Words and Images

Introduction by Janice Carlisle, Professor of English

At the beginning of this seminar, originally called "Writing about Words and Images," the Fellows and I set ourselves the goal of answering a deceptively simple question: Do the ways in which we analyze a subject depend upon whether it is a verbal text or a visual image? We broached this question so that we could think about three age-old problems: How are images and words are related to each other? Are they by nature different from each other? Can they be understood by analogy to each other? The hunch about the complicated issues to which these problems would lead turned out to be accurate, but our eventual answer to our first question might seem to be a truism. During our final meeting we concluded that, yes, there is a difference between how people write about words and images; but that difference has little to do with the nature of those two media; rather, we realized that a person who has studied words for years is more likely to focus first on the formal features of a verbal text than someone equally versed in the analysis of images, just as a person used to studying images is more likely than a literary critic to ask initially how the techniques of a picture create its meanings. On the principle that the journey is more important than the destination, I don't think that there is any reason to bemoan the fact that we did not come to a theoretical breakthrough on problems that have bedeviled thinkers since Plato and Aristotle. In fact, for us as teachers, it was useful to be reminded how much what our students are able to learn depends on what they already know. Moreover, a seminar devoted to developing projects that link verbal and visual texts is particularly suited to the image- and media-saturated world in which our students, for better or worse, will have to find their places.

In our theoretical considerations of the three basic word-image problems, we considered a wide range of ideas – among them, the classical dictum that a picture is a mute poem and a poem, a speaking picture; Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's concept of words and images as neighbors who should be separated by a sturdy fence; and W. J. T. Mitchell's conviction that all representations are mixed-media imagetexts . Also useful was the thinking of Scott McCloud as it is presented in the chapter of Understanding Comics in which he sets out seven different ratios in which words and images can be combined. Equally important, I think, is the example that McCloud offers of a writer who composes in both images and words: he communicates his seven ratios by showing how each would look in the panel of a comic strip. In that sense his chapter had its counterpart in the book that served as the backbone of the seminar: Edward R. Tufte's Visual Explanations . Tufte's work in information design has been justly celebrated, most recently by a presidential appointment to a committee charged with ensuring the transparency of the federal government's accounts of its use of stimulus funds. Tufte directly confronts the question of whether texts and images are in any theoretically or practically productive way analogous to each other; and his beautifully designed chapters prove again and again that that is the case. To evaluate the applicability of all these different ideas, we read short stories paired with visual images of comparable subject matter, and we also took as test cases two iconic images, Grant Wood's painting American Gothic and Dorothea Lange's photograph Migrant Mother , as well as one iconic text, "Letter from Birmingham Jail" by Martin Luther King, Jr.

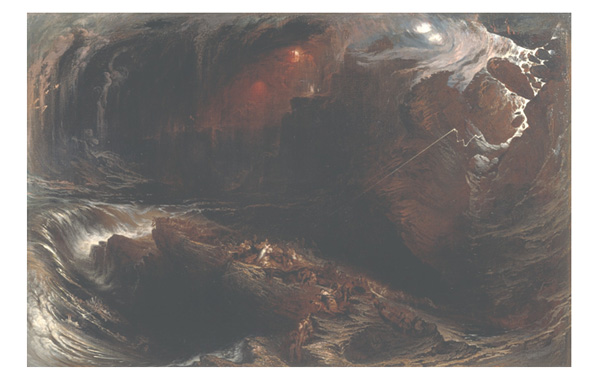

The high point of the seminar came, in my view at least, one Saturday morning when we visited the Yale Center for British Art. Following the method developed by Linda Friedlaender, Curator of Education there, and used by her with students as young as those in kindergarten and as old as those in medical school,< 1< the seminar participants were asked to look closely at an epic painting depicting Noah's flood, The Deluge (1834) by John Martin.

John Martin, The Deluge (1834), oil on canvas, 66¼ x 101¾ inches. Reproduced courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

For the first twenty minutes of this session, the Fellows responded to only one question: What do you see? When they were invited to turn their observations of what is physically visible in the painting into arguments about its meaning, they came up with an astonishingly original way to read the painting. The critical literature on The Deluge is, from the nineteenth century to the twenty-first, consistent in its conclusions about the status of the human figures in the painting: they are "reduced to triviality, dwarfed by the immense natural [and] divine forces ominously arrayed against them"; or, in the words of another writer, these characters play "the humiliatingly insignificant role of top dressing on a rock of ages."< 2< From their twenty-minute session of simply listing what they had seen, the Fellows focused instead on the images of damned humanity in The Deluge as figures not only to be taken seriously as central to the meaning of the painting but also to be accorded sympathy and even admiration.

John Martin, The Deluge (detail)

Despite their obvious peril or perhaps because of it – many of the human beings portrayed in The Deluge engage in acts of caring and even piety: a man tries to save a woman from falling into the abyss, many figures raise their arms in supplication in hopes of being saved (hardly an action characteristic of those who have turned away from God), and the pose of the ancient and righteous Methuselah prefigures the crucifixion. According to the account offered by the Fellows in the seminar, The Deluge visualizes values of compassion and community. This reading hardly supports a strictly biblical understanding of Noah's flood as God's well-justified destruction of human beings who have become irreparably evil. Identifying the human beings in the painting as objects of sympathy and identification is, no doubt, a distinctively secular reading, one that would have surprised its original viewers, but the analysis that the Fellows offered is, for this reason, a remarkably valuable revision of conventional ways of understanding The Deluge . Just goes to show what you can do when you take time simply to look.

The curriculum units presented here similarly prove what can happen when one asks one's students to look. The Fellows who participated in this seminar represented a wide range of subjects and grade levels, from art in K-4 to English and history in middle school and creative writing in high school. Their units reflect this diversity by construing the relation between words and images in different ways and for different pedagogical purposes. Certain commonalities, however, emerge. In the first two units published here, which apply their approaches to both reading and writing, Timothy Grady and Julia Biagiarelli define image , not as an object of direct visual perception, but in its traditional literary-critical sense as a verbal evocation of a visible phenomenon. Tim Grady uses the thinking of John Gardner about the nature of fiction to develop a series of writing-workshop activities that help creative writers in high school take full advantage of the descriptive power of language. Like Tim, Julia Biagiarelli asks her elementary-school students to pay attention to the use of images in what they read so that they can produce more fully visualized prose in the stories that they write.

In the next set of units, Laura Carroll-Koch, Carol Boynton, and Heather Wenarsky explore the ways in which images can support writing instruction. Drawing on the findings of neurophysiologists about the two hemispheres of the brain and their separate processing of visual and verbal data, Laura Carroll-Koch created the Trait Mate, a simple but easily elaborated symbol for a fictional character. Developed in her teaching of writing to second-graders, this visual device allows students to plan how to characterize the people in their stories, how to involve them in actions and in relations with other characters, and how to revise their stories into fully visualized narratives. Like Laura, Carol Boynton looks at published research, in her case the studies that prove that the act of drawing improves the quality of student writing. Her unit proposes activities that turn students' eagerness to talk about images into increased abilities to make connections among their reading and their experiences and the world in which they live. Heather Wenarsky's unit, the result of her work with special-education students in the ninth grade, encourages students to become better writers by learning about specific images from a World War II poster to an ad for a laptop and reading about their historical contexts.

In the final and largest set of units, Kristin Wetmore, Medea Lamberti-Sanchez, Sean Griffin, Tara Stevens, and Melody Gallagher all present units that balance words and images for the study of art objects or history or literature. In her unit Kristin Wetmore offers a particularly flexible and extensive way to include two iconic paintings and one iconic photograph in the course of a year-long study of AP art history by placing them in the verbal context of the historical events that they depict. Medea Lamberti-Sanchez also brings together words and images by engaging what she calls "visual vocabulary" to help students in fifth to eighth grades understand the complexities of the American Revolution: portraits, paintings, and maps provide visual incitements to learning and retention. American history is also the focus of Sean Griffin's unit: to prepare students for the reading of Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men , he proposes devoting a full week to various activities during which students collect and display images of the Great Depression and analyze their meanings in what Sean calls "mini-research projects." Tara Stevens's project similarly brings together language arts and history to help eighth-grade students as they read one of Chris Crowe's accounts of the tragedy of Emmett Till, Getting Away with Murder . Tara's unit offers models of different approaches to the reading of different kinds of texts and images so that students will recognize both the constructed nature of historical accounts and the continuing need to pursue the ideals of social justice. Melody Gallagher, like Tara, is interested in helping students in her fourth-grade art classes think of themselves as agents of change by becoming artists who are also art critics. Melody takes an unconventional route to her pedagogical goals by presenting to young students the works of living artists who take history as their subject. Students then curate an exhibition of their own art – complete with the labels that prove that they understand the meanings captured in their pictures.

Melody Gallagher's unit, like many of the others published here, conjoins different disciplines as it finds new ways to correlate verbal and visual texts, both those that students create and those that they read. Since the career of the great Victorian art critic John Ruskin, it has been commonplace to talk about reading a painting; but in the context of the teaching of writing, it is also appropriate to talk about seeing a text. The revised title to this volume of curriculum units attests to that fact. If most of us take for granted that we write with words, these units allow us to understand anew that we can also write with images – with them as prompts, with them as subjects, and even, as Laura Carroll-Koch's unit demonstrates, with them as records of what students see when they write.

Janice Carlisle

1 Jacqueline Doley, Linda Krohner Friedlaender, and Irwin M. Braverman, "Use of Fine Art to Enhance Visual Diagnosis Skills," Journal of the American Medical Association 286 (September 5, 2001): 1020-3.

2 For these quotations see Angus Trumble, "John Martin, The Deluge , 1834," in British Vision: Observation and Imagination in British Ar t, ed. Robert Hoozee (Ghent: Mercatorfonds Museum Voor Schone Kunsten, 2007), 319; William Feaver, The Art of John Martin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), 92.

Synopses of the Curriculum Units

Conjuring Sight: Evoking Images in Prose Fiction

by Timothy A. Grady

Guide Entry to 11.01.01:

Nearly everyone who reads has had the experience of being transported to another world – of becoming so engrossed in a narrative that he or she becomes almost unconscious of the act of reading. In these cases, the prose an author constructs becomes so vivid as to replace, in a small way, reality in a reader's mind for a time. The evocation of rich images is a hallmark of well-crafted fiction. This unit is a workshop that helps students learn to evoke vivid and continuous images in the fiction they write. The unit involves a heavy amount of writing and should be administered to advanced level juniors and seniors, though it can be modified to great effect for lower ability levels. As for the classroom texts required, it is up to the individual teacher as to which texts he or she might use; that said, using John Gardner's The Art of Fiction in the beginning of the unit is helpful in clarifying its underlying concepts. The unit is four to six weeks in length and uses the PROPEL methodology developed by Project Zero at Harvard.

(Developed for Creative Writing: Novella, Junior and Senior grades; recommended for English and Creative Writing, Junior and Senior grades)

Communicating Life Experiences through Words and Verbal Images

by Julia M. Biagiarelli

Guide Entry to 11.01.02:

The objective of this unit is to teach narrative writing to upper-elementary-school students. The unit describes the elements of a narrative piece and the writing process, from generating ideas to revising and editing. There are sample lessons that concentrate on teaching particular skills that will enhance the written compositions of elementary-grade students. Many of the ideas are drawn from authors who are experienced teachers and have successfully taught writing to children of all ages.

Students will be instructed in: identifying components of a narrative through listening to stories and viewing images, creating interesting opening lines, maintaining a structure and purpose in the story, using descriptive writing effectively, exploring different points of view in different versions of the same story, relating images to writing, using literary devices, developing characters, writing for a particular audience, following models of writing they enjoy reading to create their own work, as well as revising and editing. The unit is also intended to align with the Connecticut Mastery Testing requirement for third- and fourth-graders that involves composing a narrative in the direct assessment of writing.

(Developed for Writing Block, grade 4; recommended for Literacy Block and Writing Block, grades 3-5)

The Trait Mate: Visual Symbols for Narrative Writing

by Laura Carroll-Koch

Guide Entry to 11.01.03:

A symbol, by its very nature, communicates an idea. When this idea is universal, connecting to a deeply familiar concept, it can be widely understood as it is translated into the language of the viewer. Its meaning transcends social, cultural, political, language and academic barriers, communicating its meaning quickly, clearly, and effectively. A symbol can also be used to explain complex ideas when words cannot and can inspire us to create the words we need by the idea it conveys. The importance of our communication as teachers is paramount, as it helps define the effectiveness of our instruction across diverse classroom settings. Therefore, I have developed a symbol to communicate concepts for writing. The Trait Mate is a concrete explanation of abstract ideas to help students think about narrative structure and elaboration when writing. It is a symbol that communicates concepts in a way students will easily understand and quickly learn, making it a powerfully effective tool for teaching writing.

(Developed for Writing and Reading, grade 4; recommended for Writing and Reading, grades 1-12, and Oral Language, grades 1-2)

by Carol P. Boynton

Guide Entry to 11.01.04:

The connection of words and images is, in reality, a large portion of the day-to-day thinking of young students everywhere. They are eagerly learning to connect words to images, working to generate thoughts and ideas using fundamental vocabulary, and composing pieces, written and drawn, to share and explain their new knowledge. Visual experiences are an important sensorial component in the development of basic comprehension. Images are all around us, and interpreting them in a meaningful way is an essential skill for learning, whether from an art object, a literary work, a historical event, or an electronic image. This unit extends the writer's workshop model to include a fully formed and formatted approach to visual literacy that will engage and encourage young thinkers and writers. The focus on connections to text (verbal or visual) – in particular text to text, text to self, and text to world – will guide students to develop strong writing skills. The unit approaches the teaching of writing and thinking with strategies such as drawing stories, making pictures to show meaning, reading pictures to develop understanding, and using drawing as part of the reading and writing process.

(Developed for Writing, grade 1; recommended for Writing Instruction, grades K-3)

Visual Images as Communication

by Heather M. Wenarsky

Guide Entry to 11.01.05:

As a ninth-grade special education teacher, I find that my students have difficulty writing in descriptive detail. In this unit, students will be able to compare and contrast events and technological inventions by writing expository essays based on visual images they view and articles they read from the 1940s, as well as from the twenty-first century. The reason I chose to incorporate the 1940s is that it was a time period of war and inventions that changed our society and impacted the current age. I believe my students will be able to stay engaged and make strong connections during this curriculum unit. According to research, human beings process visual information 60,000 times faster than text. When students are finished writing their expository essays, they will evaluate their writing by scoring a student rubric.

By the end of this unit, students should be able to think of themselves as writers, use more detail and clarity in their written work, and use more description in their writing. This curriculum unit is intended for students in high school; however, it can be modified for younger students.

(Developed for English/Inclusion/Resource Class, grades 9-10; recommended for English and History, Secondary grades 9-12, English and History, Middle School grades 6-8, and Upper Elementary grades 3-5)

Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell

by Kristin M. Wetmore

Guide Entry to 11.01.06:

This unit has students compare different approaches to a specific historical period using primary sources on each of the three iconic images selected. The three images are: Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother , Picasso's Guernica , and William Powell Frith's Derby Day . Students will discuss these works and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or report the events that they depict. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction.

Students should be able to question the accuracy of artwork and determine how the image is biased and, what message the artist is trying to convey. This unit can be used for a photography course, art history course, U.S. history course or even an English course studying literature of the Great Depression or by Dickens. These images do not have to be used consecutively, nor do they have to build on each other. They can be used individually at different points in the curriculum, if it is set up chronologically.

(Developed for AP Art History and Photography, grades 10-12; recommended for Art History, U. S. History, Photography, and Language Arts, grades 9-12)

Painting a Portrait through Time Using Words and Images: The Revolutionary War

by Medea Lamberti-Sanchez

Guide Entry to 11.01.07:

As a fifth-grade Language Arts and Social Studies teacher, I encounter difficulties teaching my students to (1) make real-world connections to the text, (2) build their vocabularies, and (3) connect visualization to comprehension retention, especially if they are reading a historical text. This unit on the Revolutionary War helps my students connect the past to their present lives. This unit uses visual stimuli as the main tool to connect images to textual information. Portraits of people, places, and major events like The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere , are examples of the visual stimuli used to enhance the students' background knowledge and comprehension. In addition, maps are used to help students locate key battles and places. Information is presented using graphic organizers like the Venn diagram to help the students organize the material introduced to them at the start of every lesson. The culminating project will ask students to choose any mode of visual representation that they have learned about to devise a storyboard depicting one or more events of the Revolutionary War. The unit is designed for students in grades five to eight.

(Developed for Language Arts and Social Studies, grade 5; recommended for Language Arts and Social Studies, grades 5-8)

Exploring Steinbeck's World through Words and Images

by Sean T. Griffin

Guide Entry to 11.01.08:

This unit is meant to build background knowledge in my ninth-grade class before the class begins to read Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men , but the unit's approach can be applied to the study of any novel or author on which a teacher wishes to focus. My intention is to encourage students to create pieces of knowledge in a variety of forms that, when considered together and displayed in the classroom, will foster a solid image-based understanding of Steinbeck and his world that students will refer to throughout their reading. The students will be encouraged to unlock Steinbeck's world through a host of activities and assignments. The aim is help them to maintain an elevated level of interest throughout the reading and simultaneously to encourage higher-level learning and a broad knowledge base that will help students better analyze literature.

(Developed for English I, grade 9; recommended for English I, grade 9, and English II, grade 10)

Encountering Injustice: Analyzing Words and Images in the Civil Rights Movement

by Tara Stevens

Guide Entry to 11.01.09:

The assigned text in the second quarter of New Haven's eighth-grade Language Arts curriculum is an important and engaging book called Getting Away With Murder: The True Story of the Emmett Till Case by Chris Crowe. This book tells the story of Emmett, a fourteen-year-old Chicago boy who was murdered in Money, Mississippi while visiting relatives in 1955. He was killed for allegedly whistling at a white woman. The book also explores the societal context that allowed Emmett's killers to be exonerated in a court of law. This gross miscarriage of justice is often presented as the catalyst that sparked the Civil Rights movement. This unit creates cohesion across the many areas upon which this text touches. Students discover the climate and history of the Civil Rights era, while establishing a foundation upon which to connect the ideas of injustice and civil rights struggles to eras and locales beyond the South of the 1950s and '60s. Students also have the opportunity to engage at least briefly with a variety of texts: primary and secondary, visual and written, prose and poetry. While they cannot possibly tackle all of these genres exhaustively, students will encounter the idea that different kinds of texts may require different reading strategies.

(Developed for Language Arts, grade 8; recommended for Language Arts, Middle School grades, and History, High School grades)

Things That Make You Go Hmmm: The Elementary School Artist Acting as a Contemporary Art Historian

by Melody S. Gallagher

Guide Entry to 11.01.10:

Although this visual arts unit is intended to be taught to fourth-grade elementary students, it is easily adaptable to be taught through high school within a visual art or art history course. This unit correlates language arts strategies with visual arts skills while introducing students to contemporary artists who look back on history and reinterpret it for the present moment. The hope is that students will be able to become critical thinkers and change-agents within their communities by developing new narratives of their own histories. Students will be gradually guided through the process of describing artworks using both visual-arts and language-arts terminology. Students will then be introduced to a variety of contemporary artists and learn how to make connections between the artists and their works of art. Last, students will participate in creating an art show to host within their local community. By presenting students with both historical elements and language-arts strategies, this unit will achieve the ultimate goal of having students become holistic thinkers.

(Developed for Art, grade 4; recommended for Art Education and Visual Arts, grades 4-12)

II. What History Teaches

Introduction by John Lewis Gaddis, Robert A. Lovett Professor of History

Each of us is, in one way or another, a historian. We all learn from the past, whether it takes the form of what's happened in our own lives, or in those of our families, or in our neighborhoods, our city, our country, or the world. Too often, though, we talk too little about how we use the past. What's the difference, for example, between a fact, an interpretation, and a consensus? Since you can't re-run experiments in history, as you can in a science laboratory, how do you know when you've got it right? Are you trying to understand the past, to predict the future, or both? Or simply to try to figure out who you are? Why even bother with history in the first place?

This seminar sought to package what professional historians have been saying about these issues in such a way as to make their findings accessible to elementary- and secondary-level public school teachers and students. It proceeded from the hypothesis that sophisticated ideas can be communicated, even to first graders, if one starts with the students' own curiosity: if one lets them decide what aspect of the past they'd like to explore, and then relies on the skill of their teachers to help them do this.

My role was to distill the thinking of my fellow historians, drawing in particular upon metaphors provided by the "new" sciences of chaos and complexity. For this purpose, we organized the seminar around my book, The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past (2002), supplementing it with samples of both macro- and micro-history. Our objective was to show that the study of the past involves comparisons across the familiar dimensions of time, space, but also across scale . That last idea was the link between academic historians among whom I move, and the public school classrooms in which my seminar Fellows teach. For it allowed the seemingly small questions students raise to expand outward into some very big answers about the nature of history itself. How this worked is best understood by beginning with small students, and then moving to larger ones.

Christine Elmore's curricular unit for first-graders, "Buttons through the Ages," took a practical principle they all already know – that clothes must be fastened to remain in place – and asked whether fastening had always been done in the same way. The illustrations she located (as well as some real buttons she will bring to class) reveal many approaches to the task of fastening over several thousand years. But what, she will ask her class, does it mean to talk about that much time? How do thousands of years differ from the three or four years they can remember, or from the thirty or forty years their parents may recall? She'll then display a timeline, perhaps across an entire wall of her classroom, with her students a tiny speck at one of it, and the first buttons way off at the other end. She'll also show selective examples of what comes in between.

Christine's students will see from this that the function of buttons has not changed significantly over time, but that their style – how they look, what they're made of, what they cost – has varied enormously. They'll take from this an important point about history: that continuity and change coexist within it. And from this, in turn, they'll have a basis for answering the question Christine poses in her unit sub-title: is the newer always better?

Deirdre Prisco, who teaches fourth-graders, has noticed their fascination with gadgets – mostly, of course, electronic. But gadgets of one kind or another (we tend to call the older ones artifacts) have existed throughout history, and the more ancient they are, the harder it often is to determine their purpose. David Macaulay's 1979 book, Motel of the Mysteries , made this point by envisaging the excavation of a Holiday Inn, with an adjoining McDonald's, some 4000 years into the future: Macaulay's engaging narrative and drawings suggest how archeologists of that era might misunderstand our own. Deirdre has built her curricular unit, "HOT on Artifacts," around Macaulay's book, but she will ask her students to go beyond it in three ways.

The first will be to determine the uses of real but more recent artifacts that Deirdre and her students will bring to class: what was the purpose, for example, of clunky devices with rotary dials, tethered by wires to walls, into which people once spoke? The second will be to guess what future fourth-graders might make of an iPhone, or a trove of plastic water bottles, were they to run across them a hundred years from now. Deirdre's third exercise will be to point out to her students that they inhabit an artifact: the school they attend is a hundred years old, and most of the original building survives. What, then, would they have seen – how would they have dressed? – how might they have behaved? – had they walked into their school on the day, a century ago, that it opened?

The point of Deirdre's curricular unit is to show her fourth-graders (the unit would work equally well, she notes, with younger or older students), that our understanding even of the recent past is only approximately accurate – and that accuracy degrades as time passes. That's a critical issue for historians, who work with artifacts (we call them archives) all the time. But Deirdre's youngsters, through this unit, will also be able to grasp it.

Fatima Nouchkioui, who teaches Arabic to grades nine through twelve, has encountered a different kind of curiosity among her students: she is Muslim but very few of them are, and they are full of questions about Islam. Her curriculum unit responds to their questions by focusing first on the practice, among many Muslim women, of head covering, and by then moving to polygamy, a more controversial custom certain to fascinate her students. Her approach will be comparative: do similar traditions exist within the two older religions with which Islam shares roots, Judaism and Christianity?

She will show that observant practitioners of all three religions cover their heads in certain circumstances – Christian women are expected to do so upon entering Catholic or Orthodox churches, for example, as are Jewish men upon entering synagogues. Each religion has reasons for these requirements, which Fatima will explore as a way of placing the Islamic tradition within a wider perspective.

That, then, will provide a basis for studying polygamy. Fatima will explain how it works in contemporary Islam, but she will also make the point that no Jew or Christian familiar with the Tanakh or the Old Testament can regard polygamy as a wholly alien. Nor, for that matter, can Americans, given its practice among 19th-century Mormons, or the remnants of it that survive today. Her purpose will be to show, through these comparisons across time, space, and scale (the scale in this case being culture, which transcends things big and small), that what may seem unfamiliar, even alien, tends to become less so the more history you know.

Marialuisa Sapienza's curriculum unit approaches alienation in another way, through the careful reading of an American classic, Ralph Ellison's novel Invisible Man , published in 1952. Her tenth- through twelfth-graders, overwhelmingly African American, have already experienced marginalization, the theme of Ellison's book. How, though, can a teacher make use of such personal histories in the classroom? To ignore them would convey cluelessness; to harp on them would suggest hopelessness. There needs to be something in between.

One of my own students pointed out to me, not long ago, that we read the classics "because they make us feel less lonely." All great literature, I think, rests on this premise that the dramatization of particular experience can take on universal significance: that by reading Homer, or Shakespeare, or (in the case of my student, Tolstoy) we learn that others have endured what we have endured or worse, and that we can enrich our own ability to cope by seeing how others – successfully or unsuccessfully – did so. That's how Marialuisa will use Ellison.

Invisible Man is arguably the most evocative account of what it was like to be a Southern-born and educated African American in New York in the middle of the 20th century. The novel is both distant from the lives of her students (because so much has changed legally) and proximate to them (because so little has changed socially). Reading it will encourage conversations with parents and especially their grandparents who experienced this history, thereby turning them into teachers, which surely is part of what education should be. So this too is comparison across time, space, and scale, for a single novel, in the classroom of a good teacher, can open up much wider worlds.

Our final three units, all intended for high-school students, shift the emphasis from explaining the past to predicting the future. Jeremy Landa begins his with two quotes from Thomas Jefferson showing that this Founding Father – like most of his contemporaries – believed that "all men are created equal" but that some races are inferior to others. The contradiction runs throughout American history: at no point in the 20th century did it become more obvious, however, than during the 1960s, a decade dominated by peaceful civil rights protests and violent urban rioting.

Jeremy will try to explain why by focusing on two riots: one that happened, in 1967, in his home city of Detroit, and one that did not happen – but could have – in 1970 in New Haven, where he teaches. He sets up a comparison between these situations to let his students determine why their outcomes differed. In doing so, he relies on what chaos theory – a set of principles drawn from mathematics, physics, and meteorology – suggests about "butterfly effects": how small differences at the beginning of sequences can produce big differences in their results.

Having introduced this concept, Jeremy will leave it to his students to decide whether urban riots – or, for that matter, any other historical events – are predictable. Their answer will be less important than their having asked the question, for the task of distinguishing between predictable and unpredictable systems is a major preoccupation of modern scientific research. Jeremy's unit links that problem to urban sociology while focusing on histories that happened in settings with which his students can readily identify.

James Brochin's curriculum unit also focuses on violence and predictability. He will present his high-school students with brief biographies of five "domestic terrorists," drawn from 19th- and 20th-century American history, all of whom appear to have killed for causes – but without any clear sense of what was supposed to happen as a result of what they did. Their lives raise disturbing questions. Is it ever justifiable for an individual – outside of law enforcement or the military – to kill for a cause? If the cause can't be articulated, does it really exist? If it does, what distinguishes such killing from random violence, which is to say, mass murder?

Domestic terrorism is very much with us, as this year's attacks in Arizona and Norway make abundantly clear. Predicting such horrors may be impossible, but that should not preclude a search for commonalities – even if none, in the end, are found. That's the premise of the cases Jim will present to his students. In this unit too, the value lies in the inquiry – in the careful comparison of apparently dissimilar individuals who seem to share only the claim to have advanced a cause. Once again the procedure is comparison across time and space, with the scale this time being the interior of disturbed minds.

Charlene Woodland's unit, "Solving Environmental Problems," focuses on another form of violence, that inflicted upon the environment by its own inhabitants. Drawing on Garrett Hardin's classic 1968 essay "The Tragedy of the Commons," she reminds her students that human "progress" has weakened the self-regulating mechanisms that, throughout most of history, stabilized ecologies. Now the sheer pace and complexity of life is outstripping the earth's capacity to sustain it – but how do you get this idea across to technologically adept, consumer-oriented high-school students, who are themselves part of the problem?

Charlene's answer is dramatization. She will take several seemingly small situations – whether to replace a wooden boardwalk with cement or plastic slats, evidence that fireworks pollute reservoirs, the possibility of making a highway safer by destroying part of a nature preserve, whether people should give up using plastic bags because sea turtles confuse them with the jellyfish they like to eat – and have her students read, perhaps perform, the dialogues she has written reflecting conflicting viewpoints in each case.

From these, she will show the larger environmental issues at stake, as well as contrast political, economic, and ecological philosophies for resolving them. Once again, this unit will make comparisons across scale: by starting with specific cases her students can relate to, Charlene will expand their awareness outward. Their own curiosity, in effect, will instruct them.

That's what my seminar Fellows and I hope will happen with all of these curriculum units: they share a commitment to making teaching an interactive process. I'm grateful to have had the opportunity to work with – and learn from – these experienced teachers, and to the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute for having provided it. I look forward to seeing how these ideas work, both in their teaching, and in my own.

John Lewis Gaddis

Synopses of the Curriculum Units

Buttons through the Ages: Is the Newer Really Always Better?

by Christine A. Elmore

Guide Entry to 11.02.01:

Does everything get better in time as most people – including children, so prone to obsession with the latest innovations in entertainment technology – seem to assume? That is the underlying question guiding my students' exploration of the history of buttons. Buttons have not always been used merely to fasten clothes. The design and uses of buttons have gone through interesting transformations. They have a past, and their history can teach us much about the lives and times of people who lived before us.

My curriculum unit is interdisciplinary, incorporating history, reading, writing, geography and art. The lessons will be implemented twice a week for 40-60 minutes over a three-month period. I have designed this unit for primary-aged children but am confident that it could easily be adapted for use in the intermediate grades, as well. This unit contains five sections:

- 1: Teaching History to Children

- 2: Button Exploration

- 3: Comparing Buttons: Is the Newer Always Better?

- 4: Buttons and Fashion through Time

- 5: Bringing It Altogether: A Descriptive Report on Buttons

(Developed for Reading and Language Arts, grade 1; recommended for Reading and Language Arts, grades K-5)

by Deirdre Prisco

Guide Entry to 11.02.02:

Making students into time-travel archeologists will spark inquiry and interest about the past, present, and future. This unit builds higher-order thinking (HOT) skills through the examination of artifacts. History and social studies curricula that require memorizing lists of dates and events may create yawns in the classroom and send the message that studying the past is boring. This unit puts the students in the role of archeologists, discovering artifacts along with their adventures exploring the past, present, and future. Students will develop their critical and creative thinking skills by imagining themselves in the different time periods in which an artifact exists. They will use higher-order questioning strategies to hypothesize, make inferences, draw conclusions, and evaluate different artifacts. Although this unit was created with fourth-graders in mind, it can easily be adapted to any grade from kindergarten through grade eight.

(Developed for Social Studies, grade 4; recommended for Social Studies, grades 4-6)

The History of Head Covering and Polygamy Practice in Islam

by Fatima Nouchkioui

Guide Entry to 11.02.03:

In the school where I teach, the percentage of Muslim students is very small. Most students do not have background knowledge about Islam and Muslims, but from what they hear about this religion they picture Muslims as totally different in practice and customs from Christians and Jews. This unit is designed for high-school students in Arabic class but can also be used in other disciplines like social studies. The purpose of this unit is to teach the students that although we look different, we may have something in common and should respect each other no matter how different we may be. The focus is on the similarities among three monotheistic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – with emphasis on the use of head cover and the practice of polygamy.

I chose to address these topics in particular because they are the two stereotypes my students often use to identify Muslims. Through this unit, students will learn that head covering is used in a variety of cultures for religious and non-religious reasons. Students will also learn that in ancient times head covering was used by Jews, Christians, and Muslims as a sign of respect for their worshiping place – whether a synagogue, church or mosque – and that for Islam in particular, head covering is used to protect women from molesting eyes. On the other hand, students will learn that Islam did not initiate polygamy and that, in the past, it was practiced among followers of Judaism and Christianity, as well. Students will also learn about the reasons polygamy is allowed today in Islam, and the restrictions on its practice.

(Developed for Arabic, grades 9-12; recommended for Arabic and Social Studies, grades 9-12)

Ralph Ellison's View of His Time

by Marialuisa Sapienza

Guide Entry to 11.02.04:

"I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor I am one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind."

The narrator of Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, a functioning body made of flesh, bone, and blood who breathes, feels, and fears, is tortured by an inexplicable dilemma: invisibility. In his troubled journey, he deals with issues of race, stereotypes, prejudice, and political ideologies that seem to open the door of respect but that ultimately increase his alienation. The unit opens with specific essential questions: "How does Ralph Ellison view his society? How much is his main character affected by Ellison's own experience? How is the structure of the novel influenced by its historical background?" With these questions in mind, the students read and thoroughly analyze Invisible Man while researching and analyzing numerous other sources, both oral and in writing, to understand and reflect upon the historical and cultural landscape of the 1940s and '50s. The unit applies differentiated instruction, and all assignments, including the final project, vary according to the students' learning styles.

(Developed for English, grades 10-12, and AP English Literature, grades 11-12; recommended for English, grades 10-12, and AP English Literature and Composition, grades 11-12)

Urban Race Riots: Are They Predictable, Preventable, and Pedagogically Relevant?

by Jeremy B. Landa

Guide Entry to 11.02.05:

Some 235 years since the United States declared independence from Great Britain and almost 150 years since the Civil War and Reconstruction ended slavery in the U.S., the nation is still dealing with racial tension. Hidden to different degrees at different times, the racial component of society results in a tension sometimes characterized by peaceful coexistence, by protests, or occasionally by violent riots. The 1960s were punctuated by rapid societal shifts in the social constructs that existed. The distance of several decades now allows space for students of history to question why these events occurred, how these events affected American cities, and whether these events are predictable or preventable. This unit attempts to explore these questions.

The unit uses chaos theory to conduct a case study on two cities that had race tension; one city, Detroit, had a riot, while the other, New Haven, nearly erupted in violence, but did not. The case study will ask students to examine individuals and events before, during, and after the conflict and generalize from both micro- and macro-dimensions of history, looking for similarities across different scales. The unit pushes students to consider how processes of thinking about race came to be accepted structures in society. Using Thomas Jefferson's only book for dramatic effect, students will understand how racial dichotomies have become an entrenched part of American society, easing only fitfully over time. This unit, at its core, should highlight the power of the individual to influence history through his or her decisions, as well as the lack of predictability of the world. This unit has been designed for grades 9-12 in United States history but could also be used in sociology, Facing History and Ourselves , or African American history courses in high school.

(Developed for Facing History and Ourselves, grades 9-12, and AP Microeconomics, grade 12; recommended for U. S. History 1960s and Civil Rights, Sociology, Facing History and Ourselves, and African-American History, grades 9-12)

by James P. Brochin

Guide Entry to 11.02.06:

The purpose of this unit is to compare and contrast five Americans who killed for a cause, even if their actions were morally repugnant to most observers then and since: Nat Turner, John Brown, Charles Manson, Timothy McVeigh, and James Charles Kopp. At first glance these men don't seem to belong on the same list. Some might even be outraged that Nat Turner is considered together with Timothy McVeigh. Charles Manson is widely regarded as insane. Whatever place they had on a religious-political spectrum, a fire, a passion of some kind, moved them to act; to further a cause, they were willing to have others die. Students will research these five men and come to their own conclusions about what characteristics or life history these men shared that might explain their ability to pull the trigger or order others to do so. Students will research the following: family history, marital status and/or issues with intimacy, employment and financial problems, history of violence, views of authority, religious beliefs, and affiliation with causes or groups. In no way do I intend to have students excuse murder by explaining causes that drove killers; nor do I intend to bring students to accept moral relativism. I start with the proposition that killing innocent people is always wrong. Students need to know that John Brown's Pottawatomie Massacre is no less evil than Timothy McVeigh's bombing of the Murrah Building, and to understand the danger from those who believe that the ends justify the means.

(Developed for U. S. History I and II, grades 10-11, and Journalism, all grades; recommended for U. S. History II, grade 11; U. S. History I, grade 10; and Journalism, all grades)

Solving Environmental Problems

by Charlene Woodland

Guide Entry to 11.02.07:

The purpose of this unit is to teach students how to solve environmental problems, drawing upon skills of research and analysis used by historians and scientists, among others. The objectives with corresponding lessons are designed to facilitate critical thinking skills. Although hands-on experiments are essential to scientific study, not all questions can be answered in the lab. Often there are other influences at work in causing and solving environmental problems – namely humans. Due to this often unpredictable variable, students, especially in environmental science or environmental studies, need a more thorough look into how humans perceive their world, also called their worldview.

Solving environmental problems requires identification of the factors that affect decision-making. The unit begins with methods on teaching research skills. This includes primary and secondary resources, credibility of resources, and proper use of citations. These skills of analysis carry over to a lesson on graphical analysis. Once students have obtained some background knowledge on worldviews, they will analyze case studies. The case studies are original and written in everyday language. The issues are regional to ensure relevancy for students, but they are easily adapted to other localities.

The unit is designed for the teacher of advanced environmental science looking for ideas on how to teach environmental ethics, economics, and the policy portions of the environmental science curriculum. More broadly, the unit may be of interest to teachers seeking to enhance students' critical thinking skills.

(Recommended for Environmental Science, grades 11 and 12)

III. The Sound of Words: An Introduction to Poetry

Introduction by Langdon L. Hammer, Professor of English and of American Studies

Our seminar used a focus on sound as a way to approach poetry. In poetry, sound is a primary organizational principle: rhythm, rhyme, alliteration – these and a host of other "sound effects" structure poetry, and set it apart from other kinds of language use. Poetry can be a daunting subject in the classroom, because it is often difficult to say what it means, and students shy away from it under the pressure to unlock its meaning. But a focus on sound postpones the question of meaning while also providing an effective way to approach it. It presents poetry as a medium of expression. It makes poetry available to anyone who can learn to listen, or to memorize and recite; and these skills can provide a basis for students to develop skills of writing and speaking as well as interpretation.

To focus on sound is to focus on something essential about poetry, then. But we can turn this idea around and see poetry as a way to learn something about sound and the essential role it plays in communication generally. We de-materialize language when we look to it for a message alone. But language is always a material form. We apprehend it through our senses. Sound reminds us of the primacy of the material, of the sensory, in our use of language. In poetry it is impossible to isolate content from form, or a message from its medium. This is true of communication generally, but poetry foregrounds it as a principle; and studying poetry helps students – at every level of school – to integrate these different dimensions of language.

Poetry is an archaic form, the most ancient of literary kinds; its patterns of sound, its structures of repetition, refer us to the earliest literary forms in culture, and to the basis of the literary and of literacy itself in orality. The primacy of sound in poetry also returns to the early history of any individual: that is, to the experience of language acquisition, when we struggle out of infancy into speech, learning to form meaningful sounds with the muscles of our mouths, and to our first experiences of patterned language in nursery rhymes, schoolyard chants, song, or readings of scripture.

Our seminar began by listening to musical performances of W. B. Yeats's "Lake Isle of Innisfree" and W. C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues," the one a poem set to music, the other a blues song we treated as a poem. (The poet Elizabeth Bishop's favorite example of a line of iambic pentameter comes from Handy's song: "I hate to see that evening sun go down.") The question I posed – How do poems, when they are not set to music, generate a music of their own? – we returned to throughout the seminar.

To sensitize ourselves to sound patterns in poetry, we discussed modern poems written in Anglo-Saxon alliterative meter by Ezra Pound and Richard Wilbur in order to learn to hear accent and alliteration. To the accentual scheme of Anglo-Saxon poetry, we added nursery rhymes – a prosody based on accent and rhyme – and some popular song forms. We explored basic principles of lineation and rhythm – in free verse poems by Whitman and Elizabeth Bishop – and moved from there to accentual-syllabic meter, with Robert Frost's "Birches" as a model. With Frost as a guide, but now as a theorist as much as a poet, we explored the concept of "tone" in poetry. We discussed Frost's notions of the "Vocal Imagination" and the "Imaginary Ear," and his definition of "the sound of sense." These topics led us toward a working definition of "voice" in poetry.

We studied the patterning of blues poems by Langston Hughes, and the use of rhyme – and ideas about rhyme – in Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism," where Pope declares "The Sound must seem an Echo to the Sense." Pope uses rhymed heroic couplets; for comparison and contrast, we looked at some poems by the recent U.S. poet laureate, Kay Ryan, which use improvised and internal rhyme, and in Thom Gunn's "The Man with Night Sweats," which moves from strict, full rhyme to slant rhyme.

Pope and Gunn both play with notions of "imitative form": rhymes – and more generally word-sounds – that somehow imitate the sense of what is being said. We turned this idea on its head with provocative, challenging poems by Sylvia Plath and Frederick Seidel and the lyrics of contemporary rappers like Microphone Rakim in which we saw how sound sometimes takes the lead to generate unexpected senses. This point brought us, in our last class, to children's poetry and the expressive pleasures and cognitive test of nonsense. We used May Swenson's inventive poems as a model, including a delightful poem made out of spoonerisms called "A Nosty Fright," and Wallace Stevens's "The Man on the Dump."

Throughout the seminar, we mixed discussion of these texts and concepts with reflection on classroom teaching. We also had time for reading aloud, individually and collectively, and hands-on, practical play with words. For example, we practiced turning prose into poetry by taking a passage of prose and introducing line breaks. We got the hang of hearing metrical patterns by analyzing the patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables in our names, and then experimented with writing blank verse individually and as a group in class. Fellows collected "sentence-sounds" overheard in the course of a week and brought them in for discussion.

Here follow the excellent curriculum units that emerged from these seminar discussions. They demonstrated the interest of sound in poetry by bringing the ideas and exercises of our seminar to bear on a wide range of classroom subjects and situations, including the teaching of reading in first grade, English as a second language, middle-school language arts, and visual art classes.

A common theme among the units is poetry's potential to engage students who are hard to reach and motivate or who require special attention. Lyndsay Gurnee will use poetry in first grade to involve reluctant readers in the pleasure and satisfaction of mastering nursery rhymes and writing for beginning readers. Jaclyn Maler Ryan, also in first grade, will use poetry to develop second language literacy for students just beginning to use English. Working against absenteeism and distraction at the other end of the school system, Patricia Sorrentino, rather than ask her seniors to stop listening to hip hop, will show them the poetic properties of rap while using the music they listen to as a way into poetry. Matthew Monahan will use poetry and (like Sorrentino) specifically rap lyrics to help students face the dread fall-term-senior assignment: personal essays for college applications.

Putting the emphasis on sound, these teachers allow their students to play with words, to practice listening, speaking, and performing, and to take pleasure in language, on the assumption that that pleasure is an essential foundation for future studies and a bridge to formal analytic writing and thinking that is attentive to tone and expression and therefore comprehension. Caterina Salamone's plans for teaching poetry to third-grade students are full of engaging – and instructive – forms of play and performance. Laura Namnoum's students will learn to hear and experiment with creating their own versions of the simple patterns of rhyme and meter that underlie the poems of Emily Dickinson and Jack Prelutsky. Elizabeth Trojanowski, using Kenneth Koch as a model, has developed an exciting program for teaching poetry writing to her middle-school children, combining reading and writing skills. Mary Lou Narowski, working with slightly older children, also combines the reading and writing of poetry and uses her focus on sound as a way into teaching literary concepts and techniques.

Chelcey Williams brings poetry to her students of English as a second language as a way for them to grasp, with limited language skills, sophisticated forms of expression. By introducing poems in languages such as German and Japanese, she will present her students' native languages and English as only two among a great variety of languages; her goal is to sensitize students to cultural difference and encourage curiosity about other languages while instilling pride in their native languages. Waltrina Kirkland-Mullins also plans to use poetry as a means of emphasizing and exploring cultural diversity. She has built a detailed course of study around the sounds of African American poetic tradition, which is so rich in expressive resources and historical resonance, as a way of engaging her predominantly African American students and developing in them positive self-images.

Sound is a matter of the senses. To appreciate sound in poetry is to develop our sensual apprehension of language through the ear and tongue. Crecia Cipriano, the only foreign-language teacher in the seminar, highlights this dimension of the subject in her alliterative title which plays on the delightful French words for common types of fruit: "Píche, Poire, Papaye, Pastèque: Breathing Life into Building Vocabulary by Exploring and Writing Poetry in the French Classroom." Amy Migliore-Dest, a visual arts teacher, emphasizes the senses by planning to explore synesthesia with her students: the mixing of the senses in poetry that draws on and responds to visual art, and visual art that similarly draws on and responds to poetry. Crecia's class will savor the sounds of French on the tongue, and Amy's young artists will listen with their eyes.

Langdon L. Hammer

Synopses of the Curriculum Units

Motivating Reluctant Readers through Poetry

by Lyndsay A. Gurnee

Guide Entry to 11.03.01:

The purpose of this unit is to identify and utilize poetry with a focus on the sound of sense and nonsense in the first-grade classroom. With this in mind, I will elaborate on how to utilize poetry as a teaching tool to spark the interest and motivation of reluctant readers in the first grade. The use of poetry in the classroom is the best way to reach out to learners of different academic levels by activating the imaginations of each individual student. Suggested teaching strategies and activities have been researched and compiled within the unit with reluctant readers in mind. By exploring the unit, you will discover how poetry may be used to aid in student comprehension and facilitate the implementation of new skills across academic disciplines.

(Developed for Language Arts, grade 2; recommended for Language Arts, grade 1)

Silence, Songs, and Sounds: Developing Second Language Literacy through Poetry

by Jaclyn Maler Ryan

Guide Entry to 11.03.02:

This unit is based on the trajectory of early language and second language development, and uses poetry as a medium through which to build early language and literacy skills in the elementary grades. Through reading, analyzing, and performing poetry, young students will learn about sound devices that make poetry fun to read, and in turn these sound devices will help teach the students skills they need to be successful speakers and readers.

Study of rhyme, repetition, alliteration, onomatopoeia, and tone, among other poetic techniques, will open the doors to language and literacy while creating fun, engaging, and meaningful experiences with quality poems to which young learners can relate. Recommended poets referred to in this unit include Eloise Greenfield, Joyce Sidman, and Jack Prelutsky.

(Developed for Literacy, grade 2; recommended for Literacy, Oral Language, and Reading, grades 1-2)

by Patricia M. Sorrentino

Guide Entry to 11.03.03:

CDs, radio, iPods, oh my! Music, music, music … a true part of who we are. Rap lyrics absorb a majority of space on many students' music devices, so how should educators capitalize on this fact? This unit is designed to teach the poetic elements of poetry through rap lyrics. Within rap lyrics all the "textbook" poetic elements can be found. Once these elements are identified in rap lyrics, students should be able to take their new knowledge and apply it to more "traditional" poetry. Developed for an English class, this unit asks students to read deeply, write formally, conduct and participate in small group and/or whole group discussions, and present/perform poetry.

(Developed for English III and IV, grades 9-12; recommended for English I, II, III, IV, and Poetry, grades 9-12, and Language Arts, grades 7-8)

by Matthew S. Monahan

Guide Entry to 11.03.04:

This unit explores the work of a number of established literary poets and considers hip hop as a relatively new subgenre equally worthy of analysis within the confines of the secondary English classroom. Although the writing of poetry is not a focus of this unit, these literature studies are ultimately used as a frame to aid senior English students in completing District Significant Task Number One, The Personal Statement.

By considering the works of artists as seemingly divergent as the twentieth-century poet W.B. Yeats and the likes of Jay-Z, students will develop a better understanding of their own positions in the academic communities they wish to inhabit and develop their voices so that they may gain access beyond the secondary classroom.

(Developed for English, grade 12; recommended for English, grades 11-12)

Igniting the Imagination: Playing with Poems in the Classroom

by Caterina C. Salamone

Guide Entry to 11.03.05:

In an attempt to inspire and motivate my students to become better readers and writers, I have developed a unit that focuses on voice, tone, expression, art and writing for students entering third grade. This unit begins with introducing poetry to the student by filling the classroom library with books of poetry. At this time, the students will have the opportunity to sit and enjoy this style of writing without any form of written work. Soon the students will begin to see poems written on chart paper up in the room. The teacher will then bring fun poems into the morning meeting circle, where poetry will be used as comic relief to start the day. The goal is to get the students hooked into poetry and excited to learn more about it. At this point in the unit, the poems can be used to develop shared reading lesson plans that will allow the class to focus on fluency through the development of voice and tone. Students will then use expression cards to animate poems. As the unit progresses, students will use art to inspire writing of their own skits from a favorite poem of their choice. To conclude the unit, students will use their new knowledge and inspiration to help them develop well-elaborated stories.

(Developed for Reading and Writing, grade 3; recommended for Reading and Writing, grades 2-5)

Listening to the Rhythm and Tone of Poetry to Increase Comprehension

by Laura J. Namnoum

Guide Entry to 11.03.06:

This poetry unit will give elementary students the opportunity to discover poetry through an inquiry-based approach. The final outcome will be that students can independently read and write a variety of poetry. They will compile an anthology of their favorite poems from published authors and their own writing. They will perform a reading of their poems aloud to the class. Students will compare and contrast authors' tones and will be able to write poems and explain the tone they chose. They will also reflect on the rhythm of a variety of poems using instruments. To accomplish these goals, they will make observations about the styles of poetry and the sounds they hear. They will start by working with free verse – working on line breaks, alliteration, and onomatopoeia. They will listen to the syllable structure in haikus. Next, students will gain an understanding of meter through two poets. Throughout the unit, students will select poems similar to the poems taught each week. Students will listen to the tone in each poem and note places that give evidence to this tone. They also will make music to the beat of the poems by analyzing different rhythms.

(Developed for Reading and Writing, grade 4; recommended for Reading, Writing, and Poetry, grades 3-5)

A Study of Poetry in Middle School

by Elizabeth Trojanowski

Guide Entry to 11.03.07:

Using a quote from Suniti Namjoshi, an Indian poet and writer, this unit asks students to write a series of poems reflecting their human animal. Namjoshi's quote, "Poetry is the sound of the human animal," is the inspiration. Middle-school students are unique in their own way and, as teenagers, need to find a positive, safe place to find their inner creature and give it voice. This unit intends to unleash that animal from within students through a poetic unit seeded in language-arts skills but nourished by imagination and sound.

Middle-school students will build an arsenal of crafts in each lesson to answer the question "How can you express your human animal in words, sounds, and emotion?" Each of the poems studied can model or inspire a different craft for each section of the unit. The crafts studied within the unit include onomatopoeia, simile, metaphor, word choice, personification, sound, and metric pattern. Students will write a collection of authentic poetry culminating in the "Animal" poem which responds to the original quote by Namjoshi.

(Developed for Language Arts and Writing, grades 7-8; recommended for Language Arts and Writing, grades 6-8)

Tone as Reflected in the Looking Glass of Sound and Context

by Mary Lou L. Narowski

Guide Entry to 11.03.08:

Sound is the thread that makes up the cloth of poetry. The role of the sounds of words in the finished product is undeniable. Poets use sound devices to create visual images and emotional responses; the sound these devices express may reinforce or clarify those images and responses. These elements add richness, meaning, and sound to the language of poetry as well as literature. The disconnection between knowledge and application – between knowing the definition of these features and recognizing and understanding how they are used within literary text – is highlighted in this unit. Using a series of analytical questions, students will explore a series of poems to become familiar with this sound sense. The awareness of sound and image as tone will encourage its appreciation. I will use these ingredients as my main consideration for an objective within this unit.

(Developed for Language Arts, Reading, and Writing, grade 8; recommended for Language Arts, Reading, and Writing, grades 7-8)

Multiculturalism, Language and Poetry: Exploring These Avenues through the Sound of Words

by Chelcey A. Williams

Guide Entry to 11.03.09:

When English language learners (ELL) come into our classroom, they feel anxious about meeting the new teacher, and they wonder whether the teacher will understand them. They may be thinking in their native language, and if the teacher is speaking English rapidly and not giving visual cues, the ELL student may begin to feel anxious. If teachers had the training in working with these students, then they would teach from day one with them in mind. Teachers would limit their speech to simple vocabulary and use as many visual cues as possible to communicate their ideas. Doing this would allow students learning English to feel more comfortable, valued, and important in classrooms, which would thus lead to greater academic success.

This unit can be used with students in grades three through six, during the writing/language arts block. The aim is to expose students to different cultures and language through poetry; and at the same time, to increase their vocabulary and comprehension in English, as well as sensitize them to the sounds of multiple languages. Also, this unit has been created with the hope that when students look at one another from a culture other than their own, they will develop a greater appreciation for cross-cultural experiences and perspectives. The goal is to build tolerance, respect, and empathy for people of different backgrounds, their culture and their language.

(Developed for Poetry and Writing, grades 3-4; recommended for Poetry and Writing, grades 3-6)

More than Rhythm and Rhyme: An Acoustic Trek through the African American Experience

by Waltrina D. Kirkland-Mullins

Guide Entry to 11.03.10:

For many African American students in inner-city public schools, reading and reading comprehension prove challenging. Related test scores for these students are often disproportionately low as compared to their white counterparts. By grade three, young learners are immersed in children's literature predominantly written in narrative form; they are expected to put scaffolded knowledge into action to make sense of text. However, a number of students – again disproportionately African American – continue to fall short of reaching that goal. Should we consider modifying our approach to how we use literature with children in the elementary grades, particularly in third grade?

An important reality to consider is that the poetic voice is very much a part of black expression. Could educators thus zero in on the elements of poetry and the poetic voice to enhance reading and reading comprehension skills for these children? Could teaching poetry from a culturally-responsive perspective serve as an empowering springboard to enhance reading and reading comprehension skills for all children? I contend, "Yes!" Targeted at students in grade three, but modifiable for upper elementary and middle grades, this unit examines this possibility.

(Developed for Language Arts and Social Development, grade 3; recommended for Language Arts, Arts, and Social Development, grades 3-5)

by Crecia Cipriano

Guide Entry to 11.03.11:

In this unit, students will learn various techniques associated with the sound of poetry, as well as some simple poetic forms that will provide them a format in which to create poems organized around thematic vocabulary in the French language classroom. Students will classify and explore vocabulary on their own terms, according to their own preferences, thus experimenting with French language while embedding its patterns and peculiarities into their knowledge base.

This set-up will provide enough structure and guidance for students to be able to focus on word exploration while building vocabulary in an expressive context that will allow excitement and enthusiasm to guide them. Use this unit to either nurture the place in your students that loves rhyme and song and sound, or perhaps to introduce them to that place while also practicing necessary linguistic elements. This poetry creation process will fulfill the language teacher's need to individualize the vocabulary acquisition process as well as supply a worthwhile reason for using that vocabulary.