Elizabeth A. Johnson

Lesson One: Gathering and Evaluating Resources

To prepare for writing a paper, students must read and analyze all of their sources. I find that using a packet with a separate sheet for each source helps students to keep their sources and ideas organized. The educator will need to space out this list accordingly, but the following can be expanded into a handout and photocopied for as many resources as you would like your students to have. This could also be uploaded as a Google Doc for students to complete online. This would also enable students to share resources easily and to quickly get an idea about whether or not the source is valuable to them, based on their peer's work.

Gathering Resources: Source ____ (ex: 1)

Source Author: _______________________________________

Source Title: _________________________________________________________

Publisher: ___________________________________ Date:____________________

- Direct Quotation 1:

In my own words:

- Direct Quotation 2:

In my own words:

- What did I learn from this source?

- Does this relate to any of my other sources?

Lesson Two: Writing the Opening to a Research Presentation

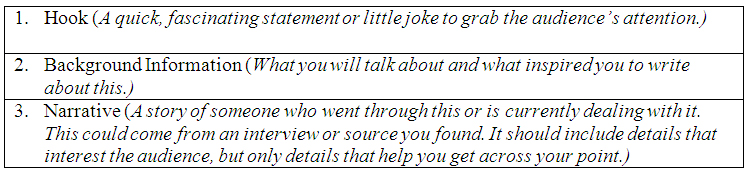

The presentation of research is separate from a typical introduction. This is part of the audience for this research paper: Intelligent peers. Since the educator can choose to have students present their work, the students will need a different introduction than the one often used in strictly written work. The outline for this oral introduction can be as follows:

A word on each piece:

The Hook should be a fascinating statement or little joke to grab the audience's attention. Students are quick to note that jokes may or may not be appropriate for their presentations. The Hook can come as a fact, such as a startling statistic. It can also be something that people already know but are seeing now in a new light.

The Background Information can be brief. It is a statement of what the student will argue, plus why he or she chose to do this. As an example, I had a student complete a presentation on gay marriage. For her Background Information she said that she chose this topic because she thought that being gay was "wrong" and she wanted to prove that people who feel this way should not be married. However, she went on, as she worked on her research, she found that the prejudice that homosexuals face and the normalness of their lives convinced her that they can and should be allowed all the rights of straight couples. This introduction caught the audience's attention because of the honesty and straight-forward nature of her revelation. It combined her research with why she wanted to learn about this, as well as clearly stating what the rest of her project would prove.

The Narrative is often a student's favorite part of the project. The CCSS call for narrative writing as part of informational writing. Far from a disconnected story written for pleasure, which students can do by the ninth grade, it is an integral part of convincing an audience to agree with the speaker. The Narrative gives a human side to any argument. By placing this in the beginning, the audience is pulled into the argument. A Narrative must be either from the student's own life or from research. It cannot be imagined, as students will ask if this is okay. The educator can guide students to an answer for this, asking if a made-up story will help to convince the audience or if it will be fake and hurt their argument. The answer is obvious to students from here. This kind of question also shows the educator that a student is currently struggling to find a narrative, which is helpful to know. To write the Narrative, students can rely on beginning, middle, and end strategies, possibly leaving the resolution to the end of their overall presentation. Always direct students to thinking about the best way to convince their audience.

Lesson Three: Assessing Source Reliability

Students often struggle to find and assess the reliability of print and online resources. Using an acronym can help students make these judgments for themselves. Using the question I often get from students, I have created an acronym. The question I often hear is, "Can I use this source?" With the word "Use," students can evaluate their source by making each letter in "use" stand for something that they must consider. The "U" is "Unbiased point of view." The "S" is "Suitable date." The "E" is "Educated author."

For "Unbiased point of view," students need to judge whether or not the source shows bias. Of course, this does not make a source moot, but it does give the reader insight into what the source is saying on the surface, versus what is truly happening. Therefore, students need to consider the bias in the piece.

In order to decide the usability of a source, students must know when the piece was published, therefore, does it have a "Suitable date." For example, if the student is researching the stem cell debate, his or her information must come from the very recent past. The date of each source matters greatly in getting accurate information. Therefore, students must use "suitable dates."

Students can assess the quality of the author in many ways. First, if there is an author, what authority does he or she have on the topic? Second, if there are multiple authors, why are they working together? Does this add to or subtract from the reliability of the source? Third, what happens when there is no author? This question happens often. If you are committed to having students find sources with reliable authors, that is, each source has an author, you will need to allow extra research time. This is where it becomes necessary to work with your school librarian because he or she will give your students tools to search articles and sources that are, most likely, reliable. By holding students to finding "educated authors," you are demanding that they find the absolute best sources, that they search past mainstream search engines. This will make for thoughtful, well-read students.

The acronym is as follows:

Can I

USE

this source?

Unbiased point of view

Suitable date

Educated author

To follow-up with this acronym and student understanding of how to assess a source, it may be necessary to ask students to articulate in writing their source choices. Without forcing students to explain why they chose a source, they may miss the author or not think about how long it has been since 1995. Like all good instruction, it is necessary to hold students accountable. To bring this into a larger context, students can do online reviews of their sources, explaining in a blog comment or on a KWHL online chart how this source helped them to

know

something new, and why the author, date, or format enabled that. This is also a way in which students can share their work and gain resources from peers.